New Metrics on Hybrid Gray-Green Levees

Hard numbers on how a certain type of nature-based engineering can help buffer cities from climate change are now available, thanks to recent research led by Rae Taylor-Burns of UC Santa Cruz and published in Nature Scientific Reports this May.

“Horizontal levees can help reinforce traditional levees and could reduce the risk of waves overtopping a levee by up to thirty percent,” Taylor-Burns says.

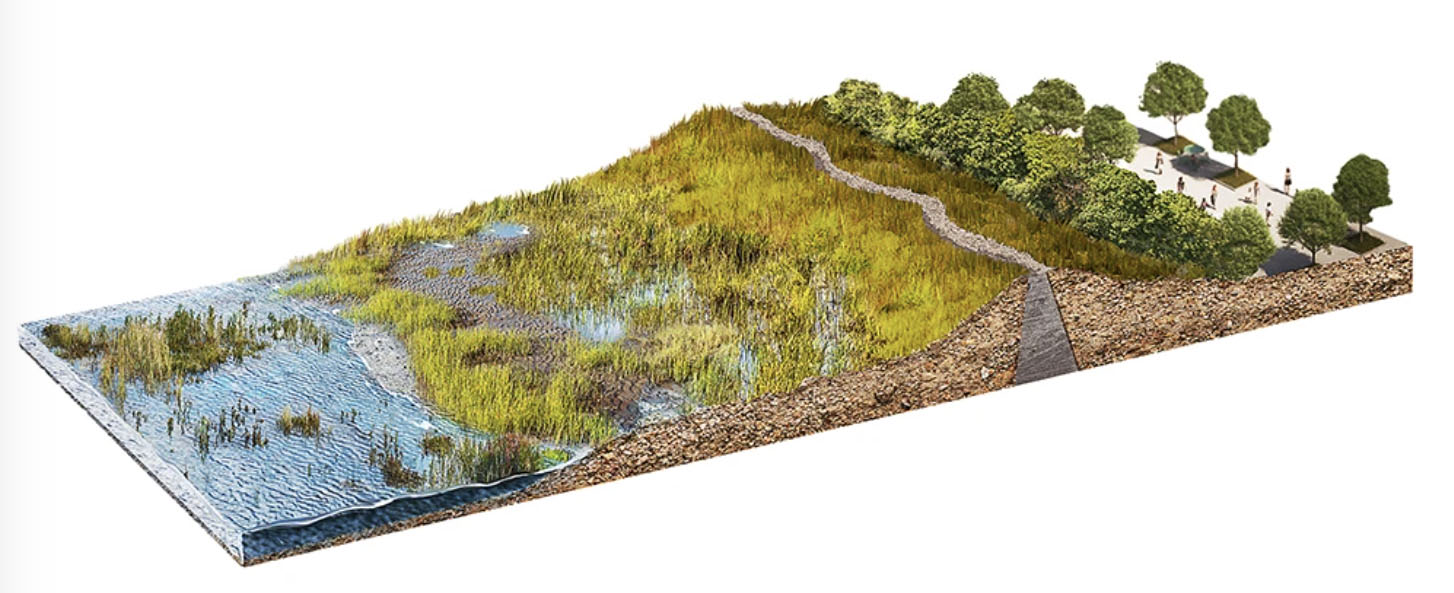

Horizontal or “living” levees are planted slopes that rise gradually from the intertidal zone to dry upland. The combination of the slope and the plants work together to slow waves that otherwise crash unimpeded on the current earth, rock, and concrete levees now protecting the San Francisco bayshore, many of which are steeper-sloped. According to modeling by Taylor-Burns, the addition of these, wider, more gently-sloped levees — added on in front of existing levees — both reduce flooding and extend the life of the older levee.

The idea of changing the shape, texture, and footprint of levees is not new. But the effectiveness of these new hybrid, gray-green levees has not been quantified until now. Taylor-Burns built a model that compared the stability and sustainability of traditional levees with horizontal levees, based largely on conditions along the San Mateo County bayshore.

“We tested a range of different widths and slopes of the horizontal levee, as well as the survival of marsh vegetation that specifically exists in the San Francisco Bay in a certain range of the tidal prism,” Taylor-Burns says. “So when we change the elevation, that also changes where the plants could survive. The model can simulate interactions between waves and the stems of plants, and so we included that as well.”

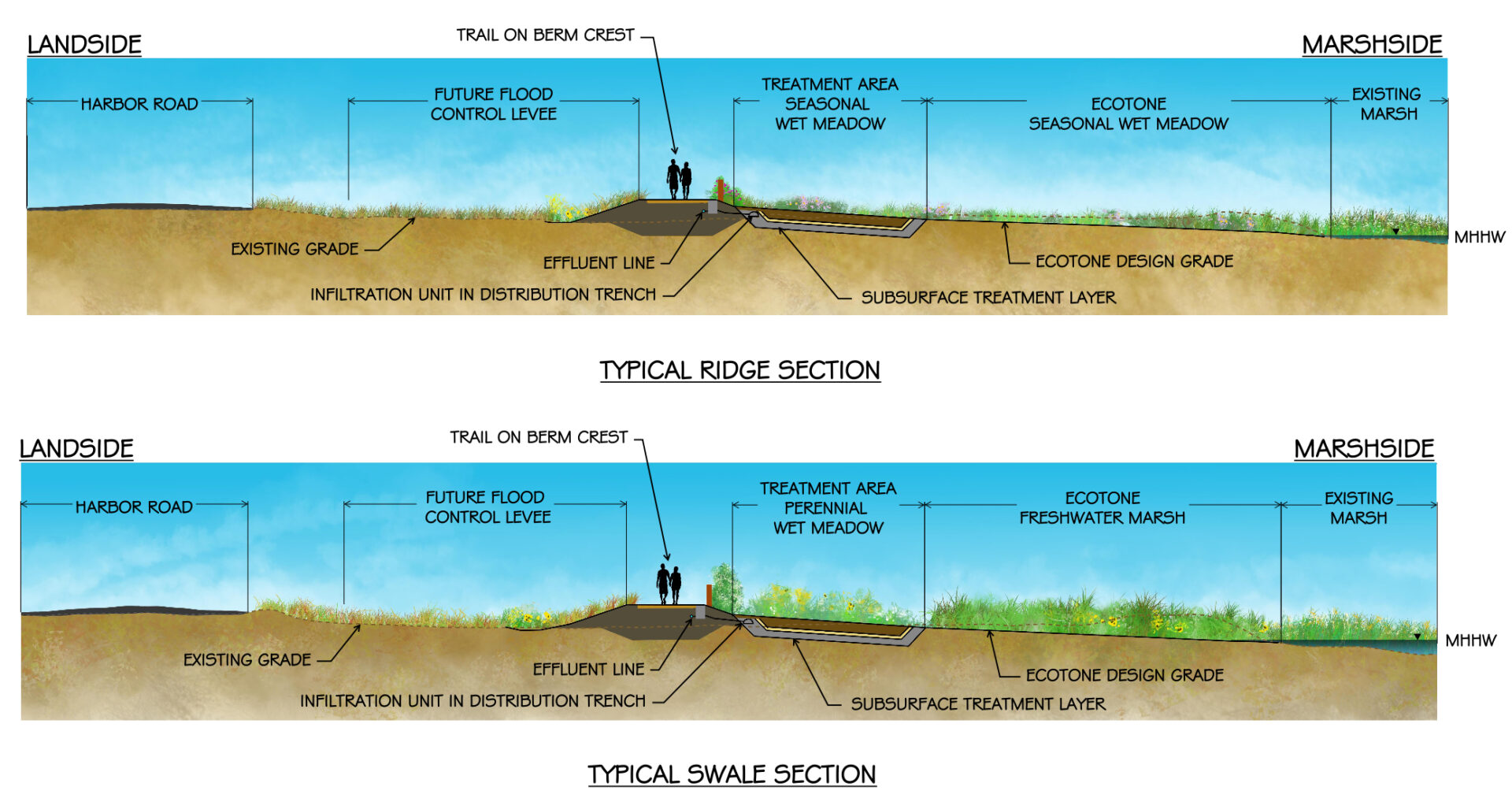

Schematic of grey-green “berm” project proposed for a Palo Alto site. According to Taylor-Burns’ study, a 1:100-sloped horizontal levee can reduce the risk of overtopping that exceeds the structural design of the levee by up to 30% with 1 m of SLR, while 1:20-sloped horizontal levees reduce the same risk by up to 20%. Art: ESA

Her research also suggests that those planning to build new horizontal levees should look for locations where there is currently no slope or transitional marsh between the levee and deep water. In these spots, re-establishing a gradient similar to that of an unaltered shoreline offers the most benefits from this kind of project.

These projects are complicated enough, however, that they will take time to plan, permit, and build, all while existing flood defenses in San Francisco Bay face increasing risk of failure as sea levels rise. These levees were not designed for projected water levels, nor for the storm surge and runoff associated with climate change and extreme weather.

“This solution isn’t a silver bullet, but it can play a role in a mosaic of different adaptation strategies,” says Taylor-Burns.

According to her paper, gradually sloping and wider horizontal levee designs both maximize flood risk reduction and habitat provision. The optimal slope will depend on the desired risk reduction, the wave and surge exposure, and the geomorphology of the levee and coastal section.

“We found that the risk of levee failure increases into the future more slowly when horizontal levees are used for adaptation on the levee system. So reducing the rate of increasing risk can lead to longer lifespan of infrastructure,” she says.

Beyond flood protection, living levees have also been shown to provide myriad additional benefits including filtering wastewater and other pollutants, carbon sequestration, wildlife habitat, and recreation. “A lot of the bayfront is industrial and not super well utilized [for recreation],” Taylor-Burns says. “Horizontal levees can make them a nice place to visit.”

Study area along San Mateo County shore. Laumeister Marsh near Ravenswood, also on the county bayshore. Photo: Rae Taylor-Burns

There are some tradeoffs to the wider, greener levees, the study finds. The main drawback is the additional cost of larger footprints — more materials, larger land purchases. But Taylor-Burns suggests that the costs of levee failure ($300 million for the Pajaro River levee failure in 2023, for example) can be several orders of magnitude greater.

Taylor-Burns believes that the engineering metrics and hydrodynamic models she used in her study will help coastal adaptation planners in justifying the construction of these hybrid, nature-based levees. Since the first West Coast pilot project at the Oro Loma Wastewater Treatment Plant was built in 2017, multiple horizontal levee projects have been initiated. Goals for the projects vary: in North Richmond, a living levee will offer recreational opportunities and buffer the adjacent disadvantaged communities from flooding. Industrial salt ponds were breached and returned to gently sloping marsh habitat in Menlo Park, while in Palo Alto, a levee will filter wastewater so it can irrigate restoration plantings.

“In California, there’s a lot of energy, and political and social will, to explore how nature can reduce risk,” Taylor-Burns says. “This is a great place to do this kind of work, and it’s a cool opportunity for scientists to meet that need.”

Citation: Illustration at top and map in middle come from Figure 1, Taylor-Burns et al.

Other Recent Posts

Reforming Rules to Speed Adaptation

Bay Conservation and Development Commission to vote early this year on amendments designed to expedite approval of climate projects.

Warner Chabot Shifts Gears

After 11 years at the helm of the Bay Area’s leading science institute, its leader moves back into the zone of policy influence.

Is Brooklyn Basin Emblematic of Regional Development Vision?

The 64-acre waterfront development adds thousands of new housing units to one of the world’s most expensive places, but questions remain about its future.

Coordinate or Fall Short: The New Normal

Public officials and nonprofits say teaming up and pooling resources are vital strategies for success in a climate-changed world.

Pleasant Hill Gets Sustainable Street Improvements

An intersection redesign with safer bike lanes earned a national Complete Streets award, while sparking mixed reactions from drivers.

Six Months on the Community Reporting Beat

The magazine worked with four journalists in training from community colleges, and began building a stronger network in under covered communities.

Rio Vista Residents Talk Health and Air Quality

A Sustainable Solano community meeting dug into how gas wells, traffic, and other pollution sources affect local air and public health.