How Collaborating with Community Really Works

“We are not looking at this simply as a public works project or to recreate the status-quo.”

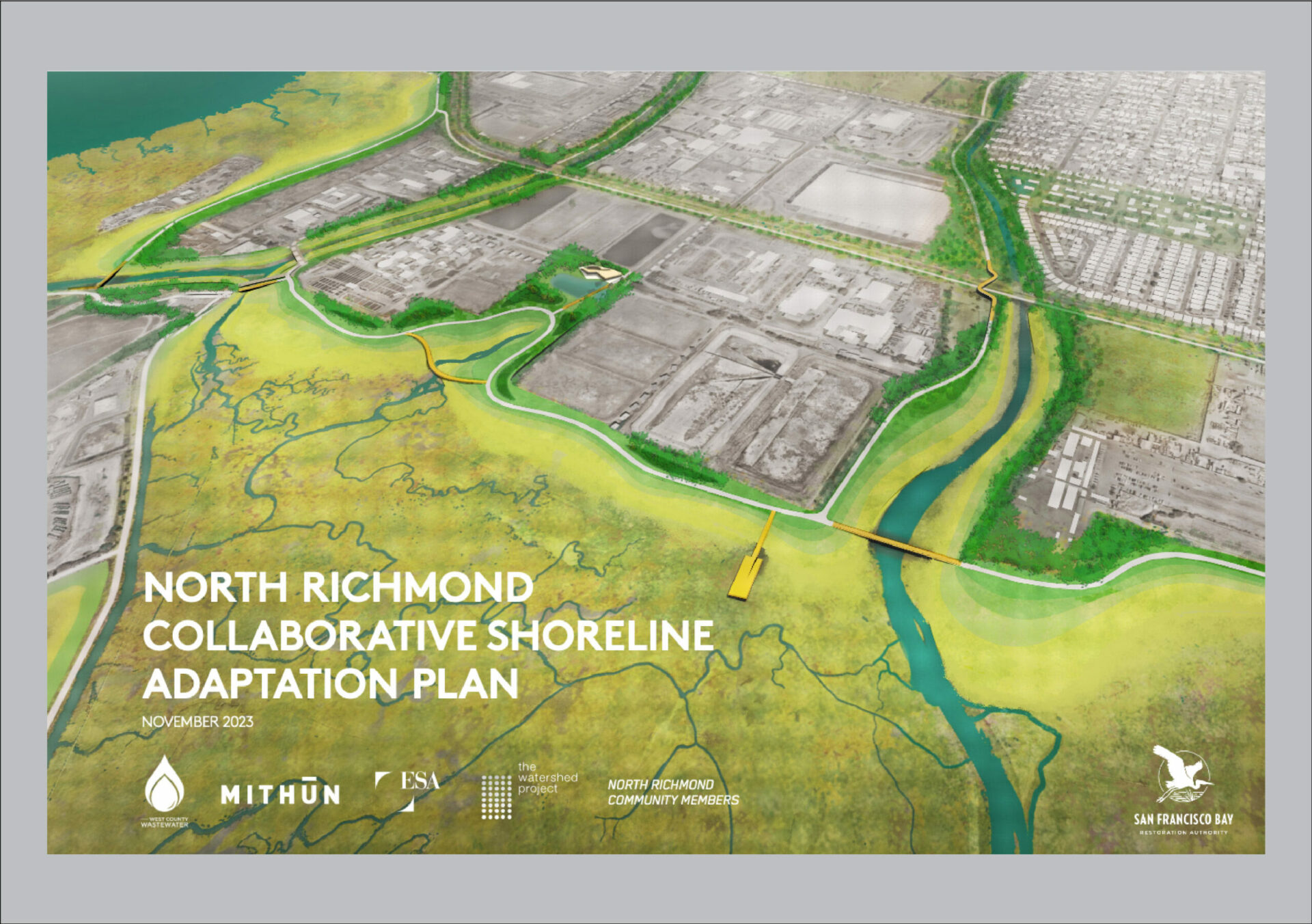

Tucked behind fences, ringed by industrial sites, and disconnected by roadways, the marshes and creek mouths of North Richmond have long felt like a reclusive neighbor—intriguing, but often unavailable. But now, after years of meetings among residents, engineers, designers, and property owners, there are big plans to connect the five miles of shoreline with the nearby community.

“When I was raising my kids, we had to pack up the car to go to other parts of the Bay Area to enjoy the shoreline, even though we knew we had one of the largest salt marshes nearby,” says North Richmond resident Cynthia Jordan. “For me, this is an opportunity to work on a piece of land that I [have] lived around and played around [all my life] and to know its possibilities.”

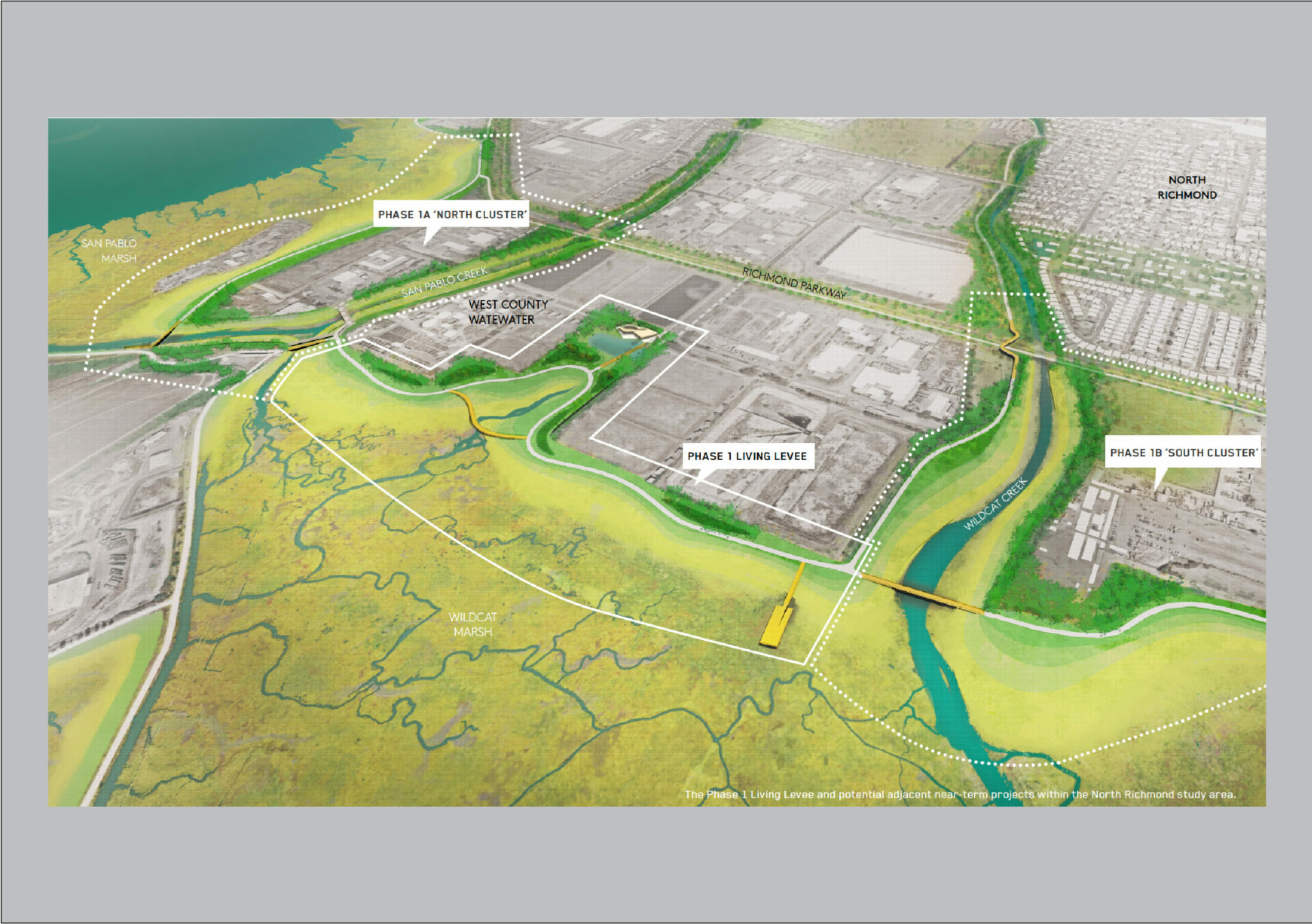

Those possibilities include new trails, kayak launches, and even an innovative levee to protect the local wastewater treatment plant from rising sea levels. Years in the works, the North Richmond Living Levee has cleared a key early design review, and the broader North Richmond Collaborative Shoreline Adaptation Plan is complete.

The plan, which included extensive input from the community, will not only protect critical infrastructure and homes from flooding, but also help sensitive species adapt, all in a way that will make the Bay and its marshes feel more accessible. The goal of the collaborative shoreline project is to create authentic collaborations and give people who live nearby the chance to help design what the future shoreline will look like.

“We are not looking at this simply as a public works project or to recreate the status-quo,” says Graham Laird Prentice, one the project leads for Mithun, a design firm working on the Richmond Shoreline project. “We want the community to benefit, not just in terms of flood protection, but also in terms of public access, habitat restoration, and jobs and wealth building over the long-term.”

The Lay of the Land

For a lot of reasons, getting a true handle on how North Richmond works is complicated. That’s why Cynthia Jordan told me to zoom out. Jordan is a former North Richmond resident (her church is still there) and longtime member of the North Richmond Municipal Advisory Council, a group created to increase communication between the Contra Costa Board of Supervisors and residents of the unincorporated portions of North Richmond. Jordan also participated in exercises involving residents in community design. To get the lay of the land and understand the challenges facing residents in the area, she suggested I cross the Richmond Bridge and look back at the city, or go to the top of Nicholl Knob, a prominent hill in Point Richmond.

Going farther away to understand something better feels counterintuitive. Most times when working on a story like this one, the closer you can get the better. But Jordan was right, “Go and see how it’s all connected,” she told me.

In the photos I took from my new vantage point on top of the knob, smokestacks and the artificial mounds of a landfill and railroad berms frame the shot. North Richmond has long been home to polluting commercial activities. Over the years, intense community activism resulted in more awareness about the impacts of poor air quality and toxic pollution. Today, the Chevron refinery, the railyard, and the landfill still very much define the community. A more modern addition are distribution centers (for companies like Amazon) and their ant-like lines of delivery vans coming and going. All of that industrial activity adds up. In 2021, North Richmond was the second most disadvantaged community in California according to the CalEnvironScreen Health Report.

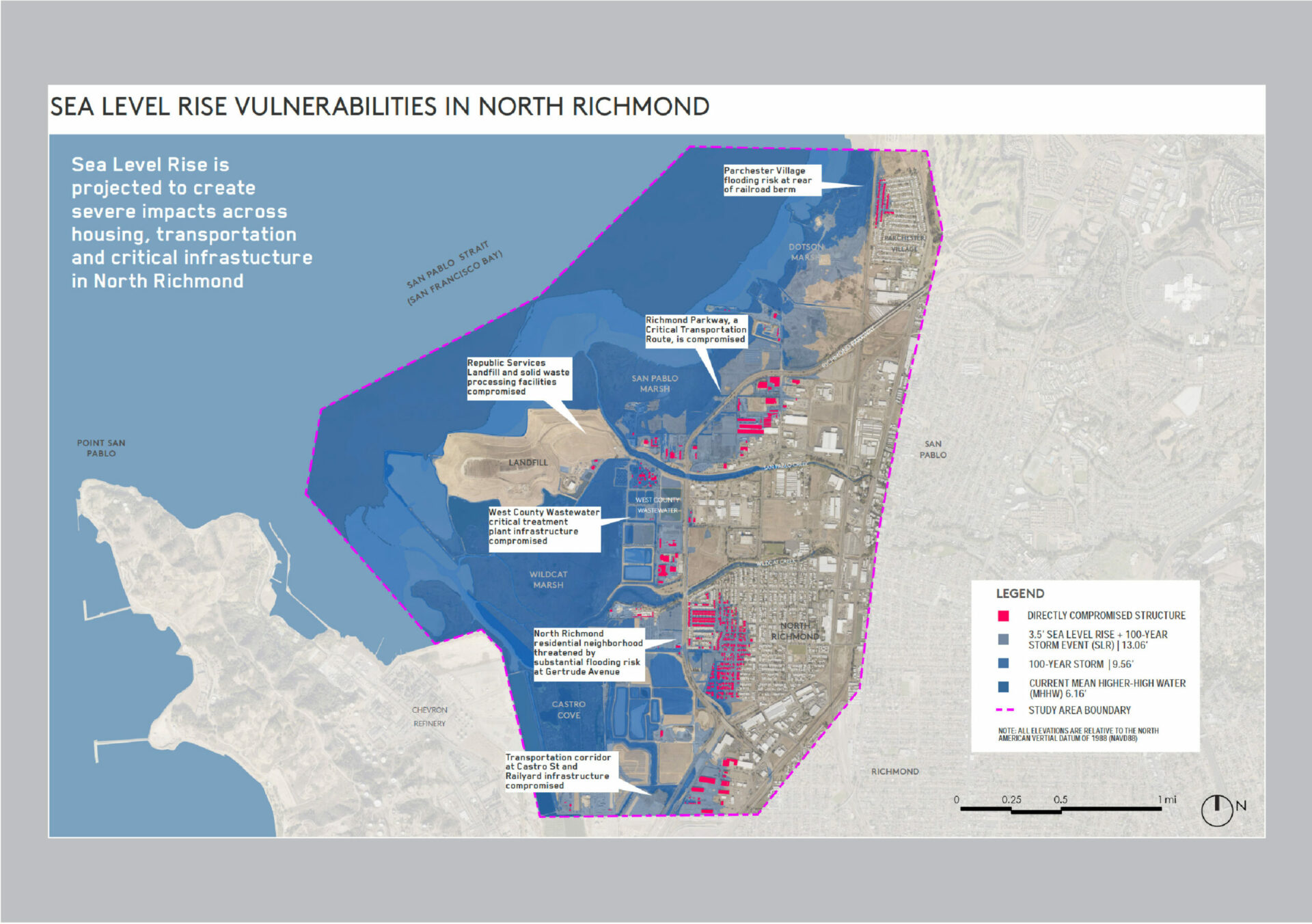

From my high-ground perch, I can also see the four-lane Richmond Parkway crossing Wildcat Marsh. The marsh sits at the confluence of San Pablo Creek and Wildcat Creek. Both watershed runoff and higher future sea levels threaten the area with flooding.

Jordan remembers what it was like when she was a kid. “During the rainy season, water would come up to our doorsteps,” says Jordan. “You needed boats to get around North Richmond, and after the water receded, all this mud would be left over—it was just a big muddy place.”

A Living Levee

Once I have some clarity on what I’m looking at, I head down to the focal point of the North Richmond adaptation plan—a 0.65-mile strip of shoreline that has a subtle but persistent briny, earthy smell that could either be coming from sun-baked marsh mud or from the nearby wastewater treatment settling ponds. On the horizon a quarter mile away, the marsh and the bay seem to blend together. It doesn’t take superpowers to understand that without any kind of intervention, this entire marsh will disappear underwater, leaving the local wastewater treatment plant vulnerable. That’s why everyone’s talking about a new levee.

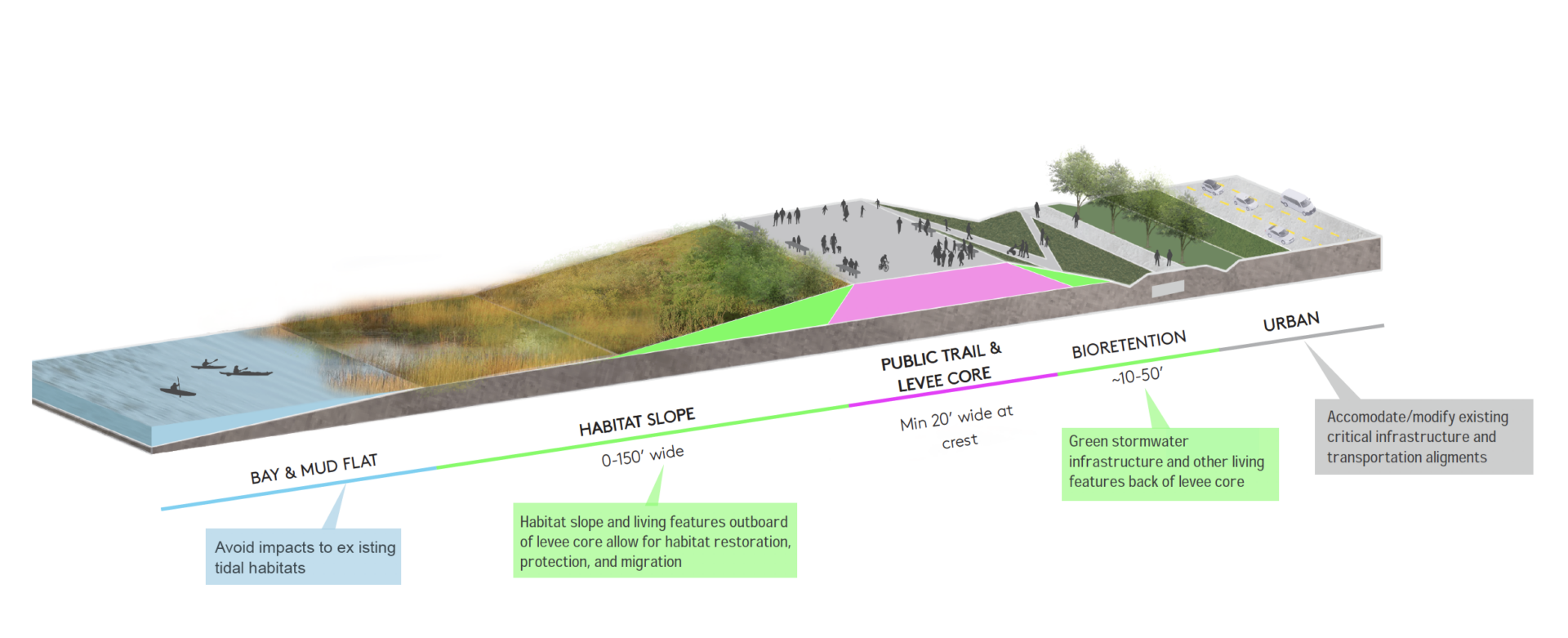

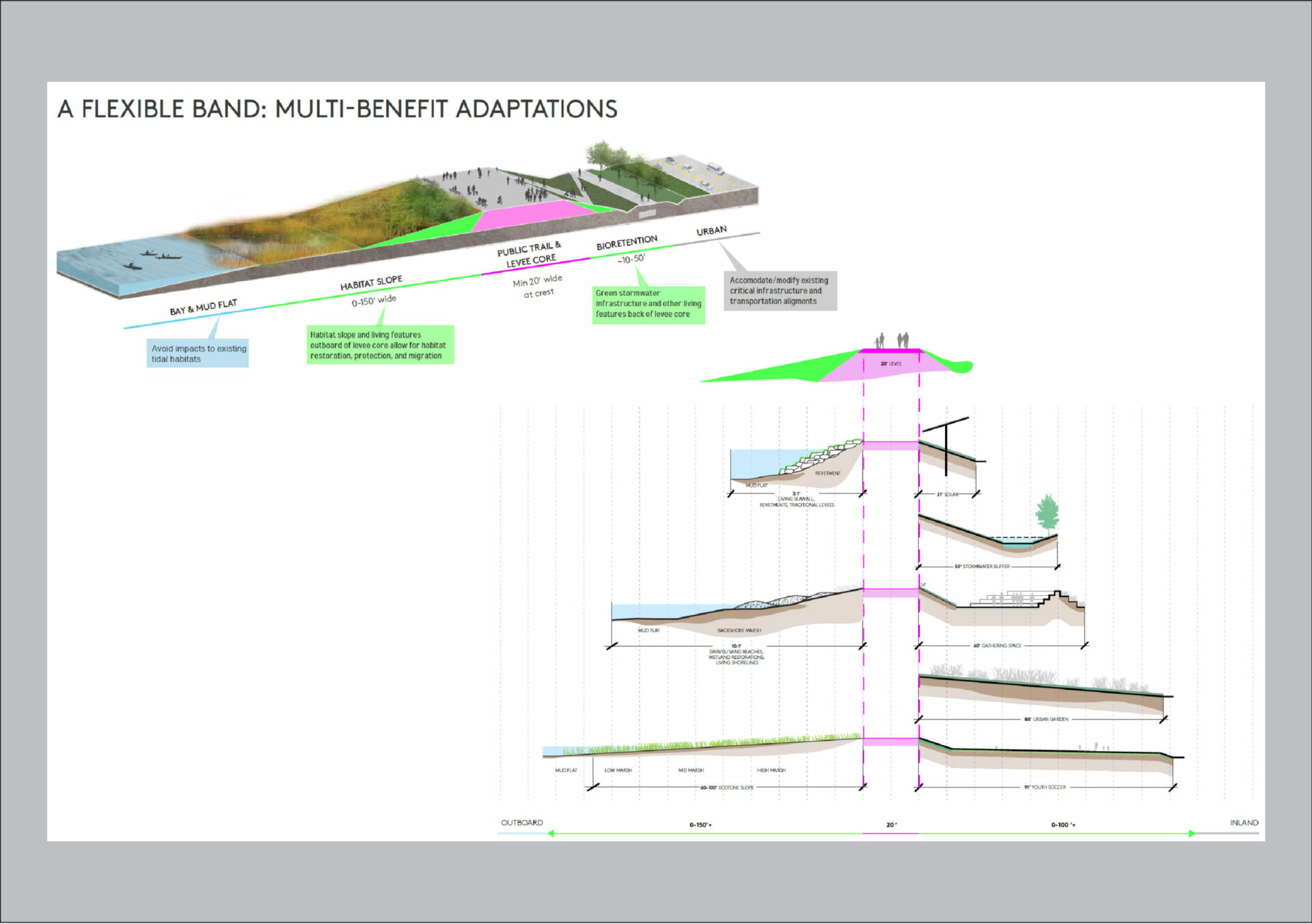

When you hear “levee,” you might be thinking about a wall-like structure of packed dirt or rip-rap, like are common in the Delta. Traditionally, levees were seen as an over-engineered solution to one single problem — flooding. But these kinds of levees can also be ecologically costly, hardening habitat and blocking natural processes.

That’s why an alternative to traditional levee building started taking shape about a decade ago. A “living” levee creates a deliberate slope of vegetation growing out from the levee core, with treated wastewater percolating and filtering through the resulting slope. The slope is a gentle gradient between the existing marsh and newly built higher ground called an upland. Currently there are about half a dozen living levee projects either planned or underway around the Bay.

“There’s been a lot of work in the Bay Area over the past few years to find ways to implement more nature-based infrastructure, and build more connections between communities and Bay ecosystems,” says Eddie Divita, a civil engineer working on the North Richmond project for ESA.

More Than a Public Comment Period

What sets the Richmond living levee project apart is that the focus isn’t just how to protect critical wastewater infrastructure from flooding, or give refuge to sensitive species like the salt marsh harvest mouse habitats transition over time. Instead, the most interesting thing about the project is the opportunity to reconnect the residents of North Richmond to the nearby landscape. As the project moved from a conceptual design to more developed drawings, what is known as 30% design—far enough along to start applying for construction funding and get the environmental impact studies underway—the level of community participation in the process has become more formalized.

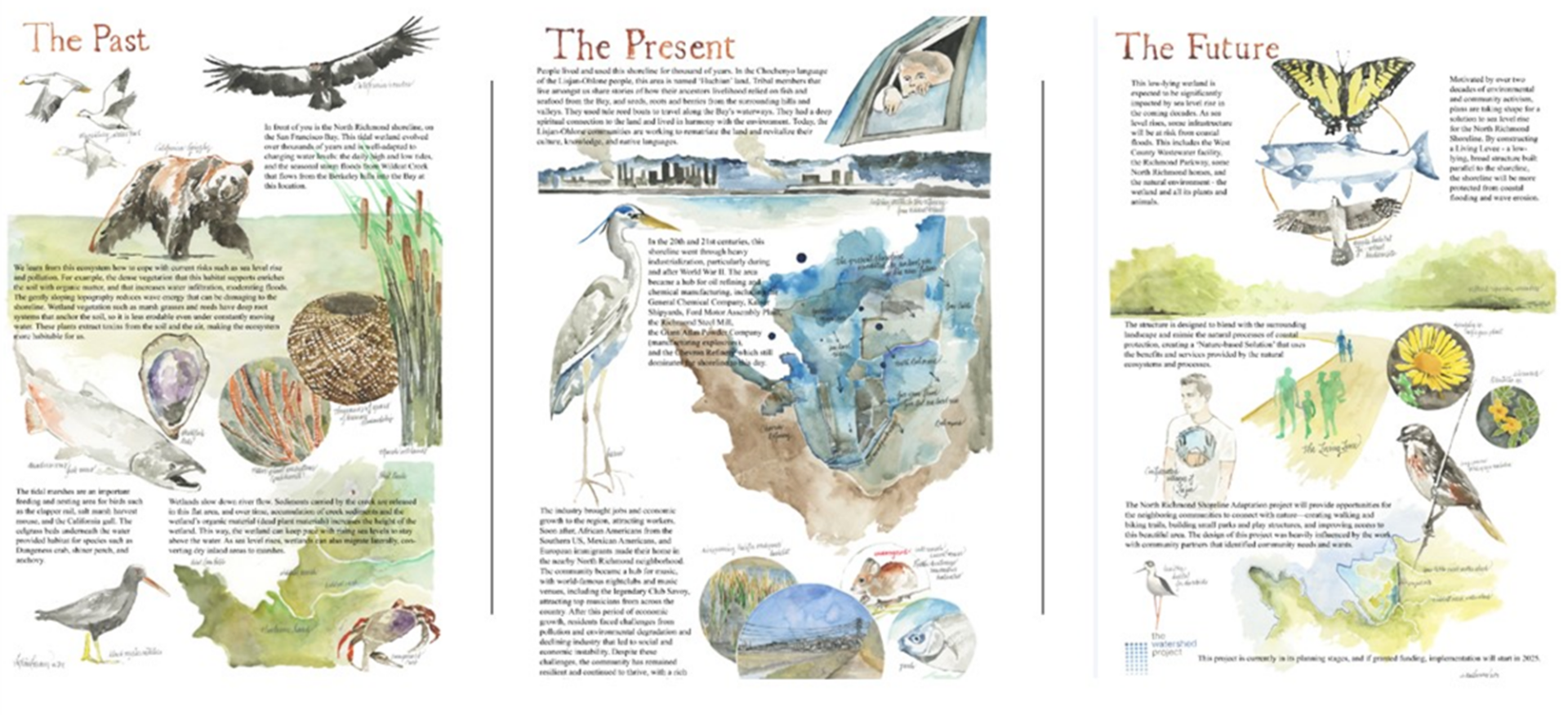

Richmond’s living levee project began in 2017 with the creation of a new community vision for the North Richmond shore. At the time, the Watershed Project, a Richmond-based non-profit that works on community organizing and watershed education, started organizing educational events. Early on that meant bringing together local residents as well as the members of the Confederated Villages of Lisjan who have ancestral ties to the marshes, creeks, and uplands that now make up the North Richmond shoreline.

The following year, the design firm Mithun got involved during the Bay Area-wide Resilient By Design challenge. The competition was created to prompt cities around the region to start preparing for sea level rise. In 2021, the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority funded more formalized development of the project by West County Wastewater, the lead agency, with a $644,709 grant, and in 2023 provided another $50,000.

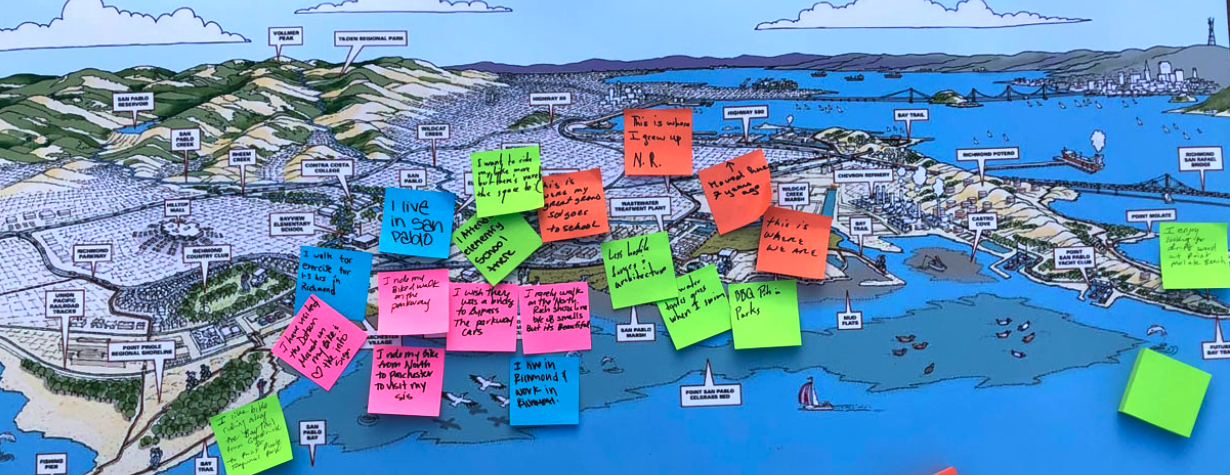

Part of the initial grant helped build on the work started by the Watershed Project and funded a long-term community engagement effort. At first this took the form of activities like tabling at events or hosting webinars and question and answer sessions with local residents, but it soon evolved into something much more substantial. “We wanted to use a rigorous community design process,” says Naama Raz-Yaseef, a community engagement manager for the Watershed Project.

The nonprofit invited interested community leaders to participate in a working group. “We started with a learning academy,“ Raz-Yaseef says. “We visited the site with the engineers and designers to talk about climate change and nature-based resilience.”

Community leadership team with new interpretive signs. Cynthia Jordan is on the right. Photo: The Watershed Project

By early 2022, the group of 20 began meeting regularly with designers from Mithun, engineers from ESA, and property owner West County Wastewater.

“We wanted community leaders to be involved,” says Joe Neugebauer, the Environmental Services Manager for West County Wastewater. “We wanted these leaders to take information back to their churches and community-based organizations. The idea was to have small focus groups where residents of North Richmond would feel comfortable sharing their ideas in a low stress environment.”

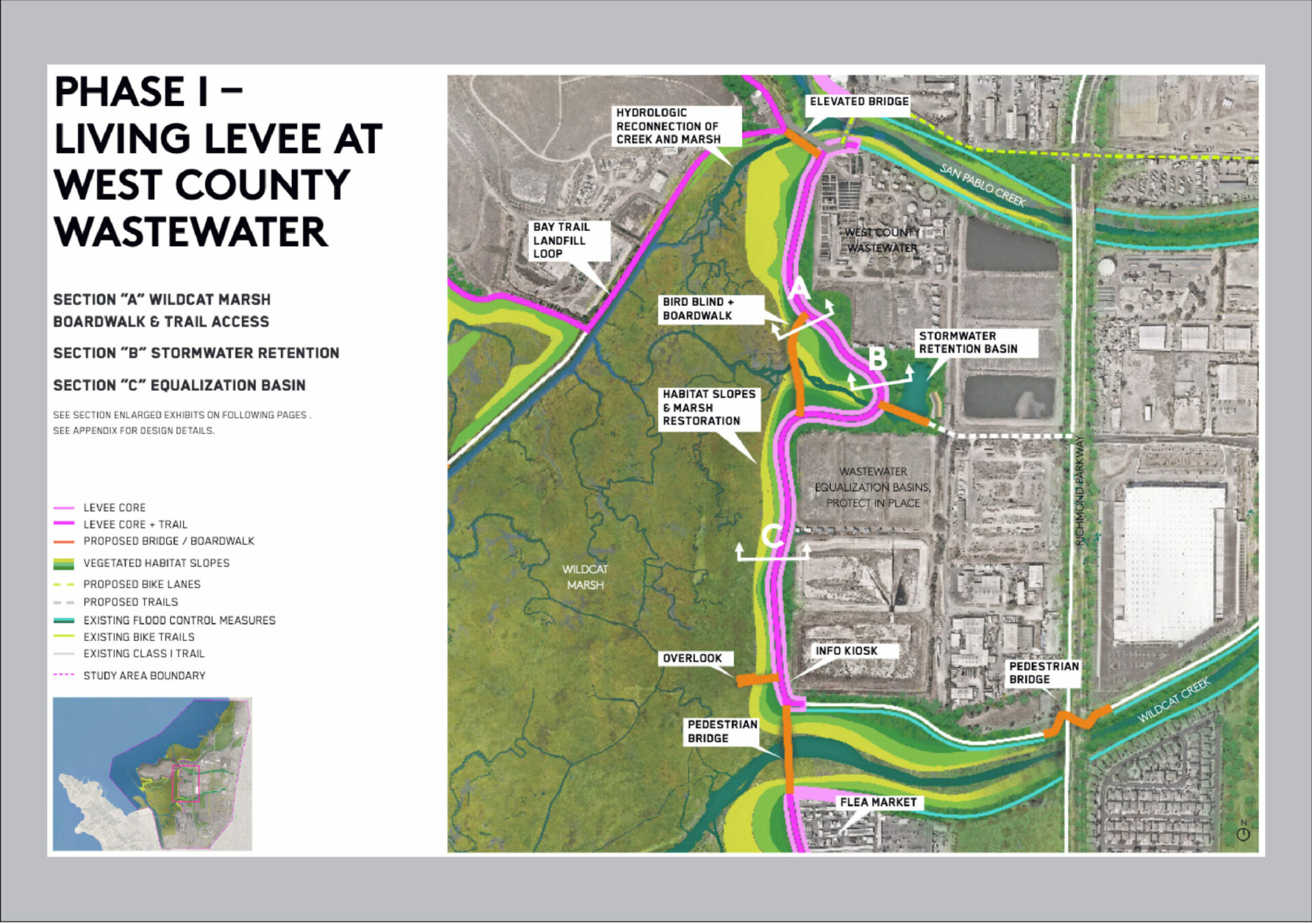

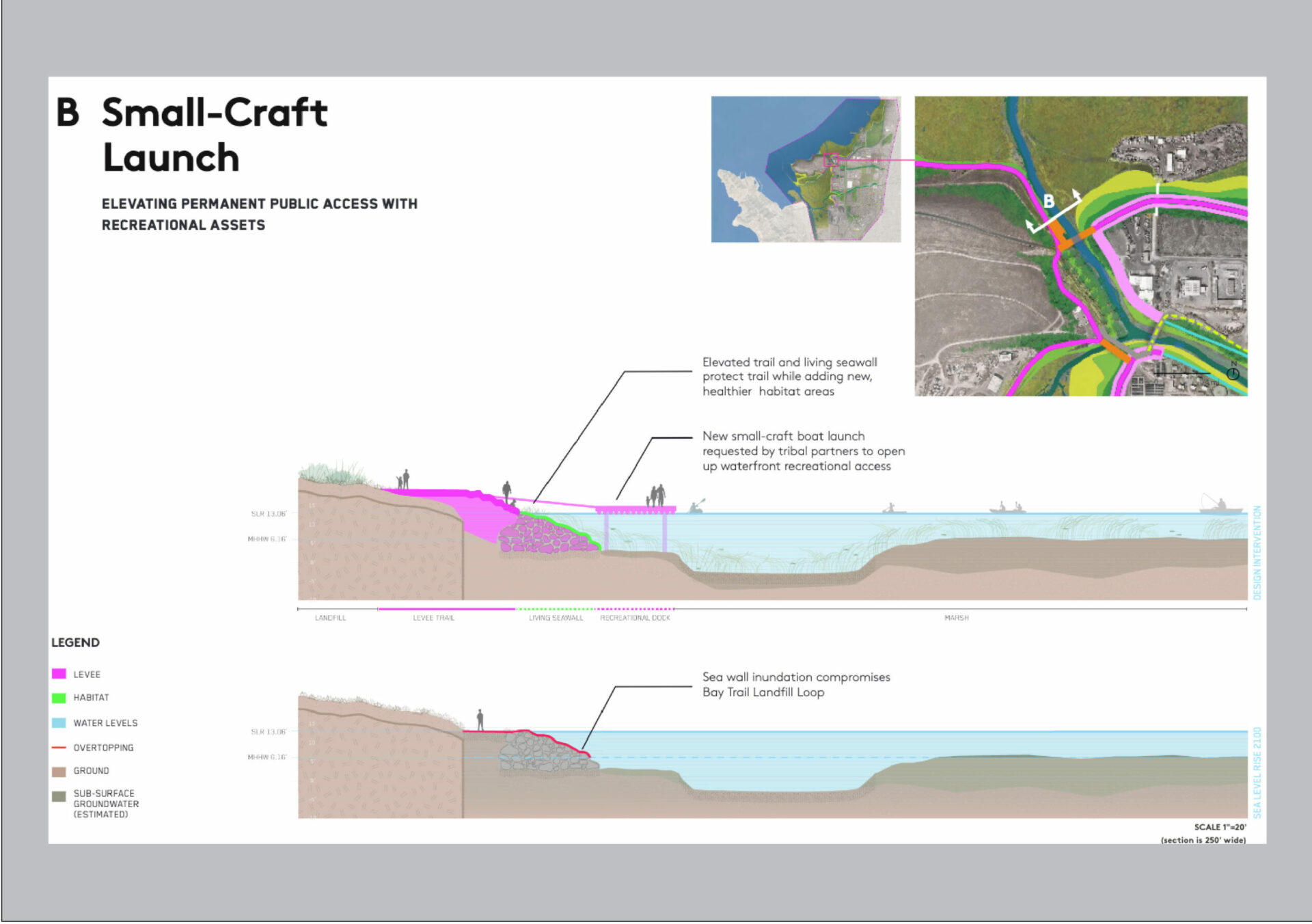

So the team subdivided into smaller groups. The first group focused on design and worked off of maps and drawings. “It was truly a novel process,” says Raz-Yaseef. “There was a better understanding of why certain things can’t happen or some of the technical challenges of the project.” The group of community members worked with the designers to imagine what new park-like amenities were possible, things like a boardwalk, parks, trails, observation decks, and even kayak launch pads.

The second group focused on community benefits, “so we beautify, but not gentrify,” says Raz-Yaseef. They thought about how to connect the improvements made possible by the levee project to other pressing issues such as housing, local jobs, and overall access to the shoreline. One idea was to create a shuttle service from the North Richmond neighborhood to the shoreline on weekends and holidays. The third group worked on community outreach, conducting a survey, and co-facilitating smaller focus groups.

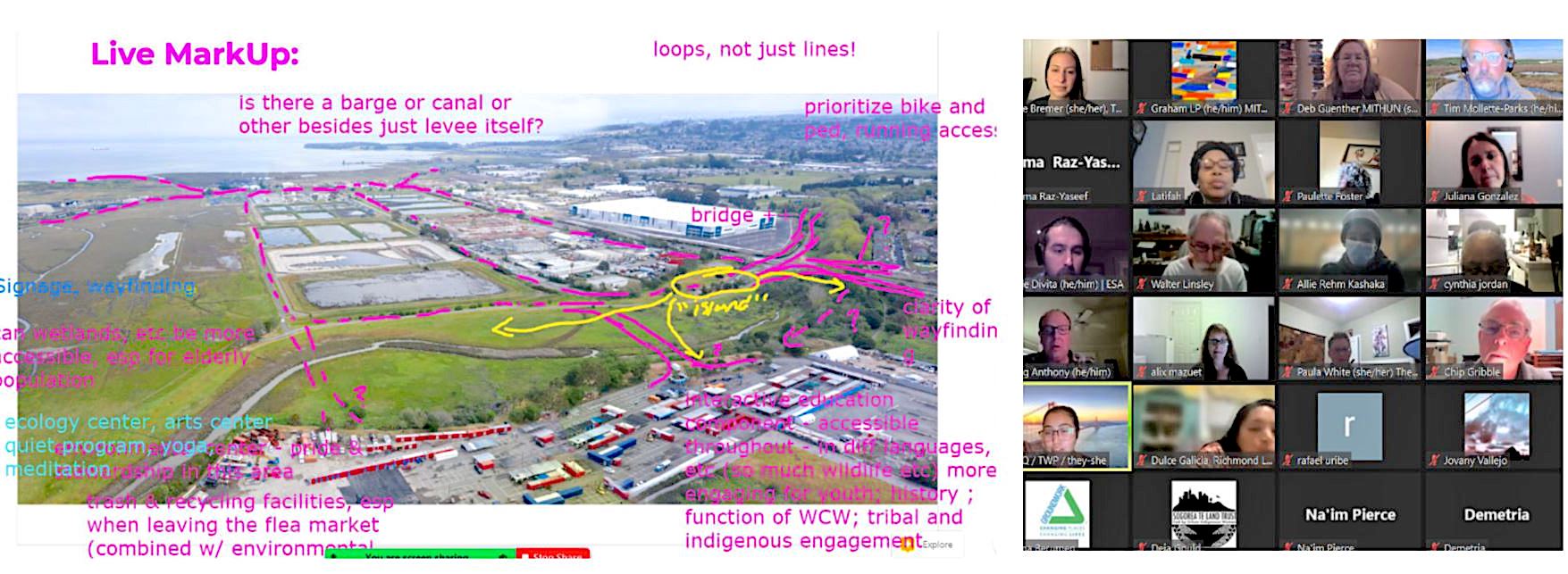

Community members were paid a stipend for their efforts. The group met largely on Zoom because most of the work took place during COVID restrictions.

Real-time Feedback

For planners and designers, the North Richmond project provided a different kind of experience . “It was new for me,” says ESA’s Divita, “working with that level of community involvement. We were sharing early work of drawings and concepts. The whole point was to give people the opportunity to provide feedback so they could help shape projects and outcomes.”

Most of the feedback centered on how to make the living levee project more connected to the surrounding neighborhoods. “The site visits were very revealing. Some residents of North Richmond had never been out there. Feedback from community members included finding places to build benches and shade and water fountains so that walkers could take breaks and take in the scenery,” says Divita. Some asked for a trail leading to the locally popular La Pulga flea market.

Another suggestion from the community of designers was to do more than just an out-and-back trail near the living levee. “Community members wanted the trail to loop around the [treatment plant] and the marsh, which is better experientially and better for public health,” says Mithun’s Graham Laird Prentice.

Members from the Confederated Villages of Lisjan asked about creating a small boat launch near the marsh in order to connect modern access to traditional usage. “So we found a place on San Pablo Creek that will work to create a yearlong boat launch,” Laird Prentice says.

Snapshots from the North Richmond Collaborative Plan. Source: Mithun

All of those ideas made it into the first round of formal design documents , which were published earlier this month. In addition to the 0.65-mile trail along the original living levee site, the plans also cover design ideas for either side of the levee—creating more trails and amenities and connections with other nearby pedestrian infrastructure.

Not all of the community’s suggestions made it on the plan, mainly because of feasibility. A floating barge with an interpretive center, for example, didn’t make the cut.

With the new design in hand, project partners are looking for additional funding. Earlier this month, the Restoration Authority granted an additional $1.9 million and other big grants are in the works. The total funding will get the project to 65% designed.

The original community working group will reconvene later this month. Their work will focus on the second phase of the project, as well as how to create local jobs to care for the shoreline’s new amenities and how to take advantage of the momentum of the shoreline project to address related flooding and access issues along the lower stretches of Wildcat Creek.

Long Road to a Safer Future

Sea level rise won’t just be an issue in North Richmond, so the community designed project is capturing attention elsewhere. The enactment of SB 272 in late 2023 compels local government agencies around the Bay to create sea level rise adaptation plans by 2034. Contra Costa County, for example, just created an ad-hoc sea level rise committee to come up with a plan for the entire county. The state mandate is generating a lot of interest in collaborative community design, like what’s happening in Richmond.

“One of the big themes with this project is capacity building,” says ESA’s Divita. “Just going through the planning process itself helped [local residents] learn how to do planning. Sea level rise is going to be a problem for decades. Hopefully the relationships and partnerships and collaborations created through this project will help the community become better at pulling the pieces together.”

At times, this project can feel like it is taking forever, say people involved with it. After all, the first meetings took place in 2017, and construction, let alone completion, still feels a long way off. “Funding is one of the biggest questions,” says Joe Neugebauer from West County Wastewater. “We have a good roadmap to get to 65% design, and we’ve been engaging with the Army Corps of Engineers to earmark more funding for 2025. Having construction dollars, that’s one of the biggest challenges. We can’t put all of this on the backs of our ratepayers.”

A change in perspective takes time. Once the Richmond levee gets built and the associated trails and amenities are visited by local residents, people will be able to look out at Wildcat Marsh and remember how a group of people worked on an idea about how they could reclaim a shoreline by protecting it for the future.

“When we go out and talk about this project, we don’t ask what people want to see today,” says Cynthia Jordan. “We ask what they want to have for their children. We are talking about a 30-year project. I know I won’t be around to see it finished.” But, she adds, “I can say I was there at the beginning.”