Half a Dozen Horizontal Levees in the Works

The buzz about horizontal levees began more than five years ago, when the East Bay’s Oro Loma Sanitary District near San Lorenzo began experimenting with building a wedge-shaped levee, planting it with natives, and irrigating it with wastewater. Since then, the specter of sea level rise, perpetual drought, and disappearing wetlands has put many sizes and shapes of horizontal levee on the region’s shoreline adaptation maps.

“These horizontal levees, and nature-based infrastructure, will buy us time so we don’t get backed into a corner with hard infrastructure,” says S.F. Estuary Partnership planner Josh Bradt, referring to the default seawall.

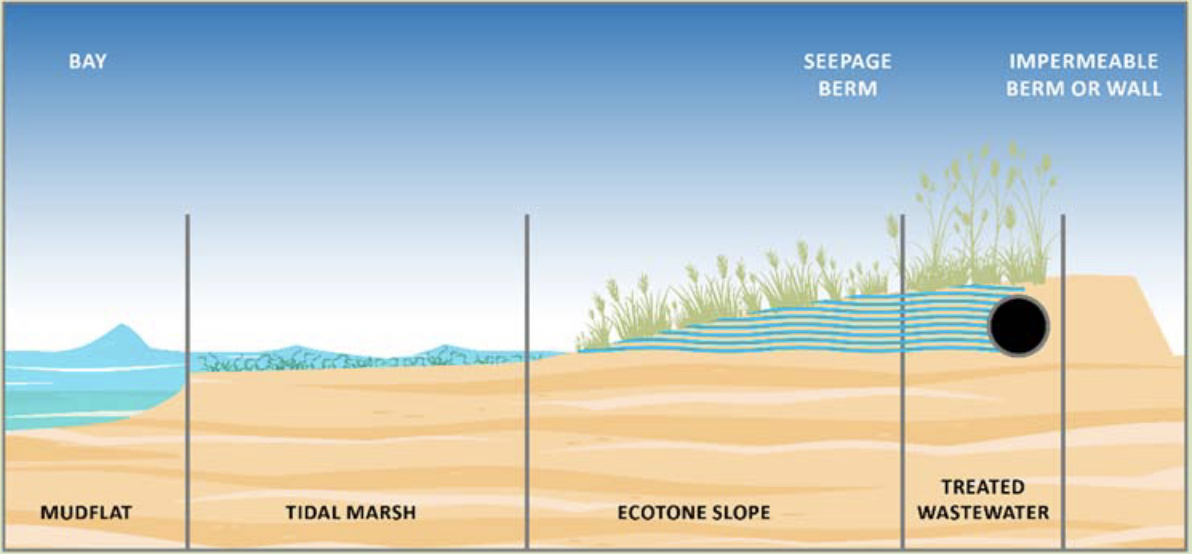

A horizontal levee is different from a dirt berm or riprapped levee — rather than a mound it’s a wedge, rather than hard it’s soft, rather than bare it’s vegetated, rather than in the marsh or bay it’s behind and inland. Grossly simplified, this new kind of levee — variously known also as an ecotone slope or habitat levee — is fast becoming a popular transitional object in the fight to get ahead of a rising Bay.

So when will we see any of these marvels built? Not anytime soon, say managers, but at least half a dozen projects are in the works, all with different priorities. Some will help sewage plants better “polish” their wastewater, some will offer flood protection, some will provide high ground for marsh mice and birds to escape high tides, some will grow native species favored by Indigenous tribes for cultural use. Many will try to do more than one of these things, all at once.

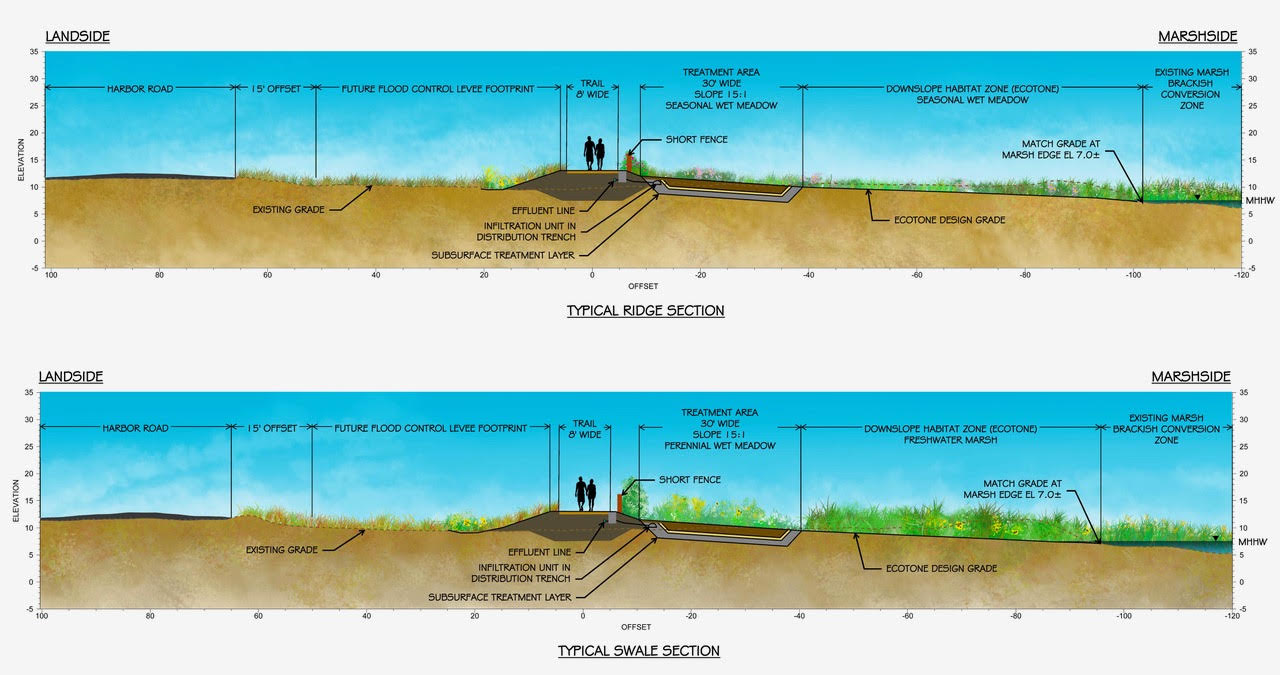

Looking around the San Francisco Bay for tangible examples, the headliner is a 325-foot-wide, 100-foot-long levee near the Palo Alto Regional Water Quality Control Plant. The project is the only one that is already 60% designed and ready to submit for permits this spring. Unique to this project was the City of Palo Alto’s early emphasis on creating quality habitat, while also polishing wastewater. Though small, the new levee will also eventually align with a much longer shoreline protection system proposed by a local authority (SAFER).

Unlike the Oro Loma pilot, the new Palo Alto horizontal levee will have a steeper slope and sit right next to a tidal marsh. Designer Mark Lindley, an engineer with ESA Associates, will be carefully watching to see if the wastewater trickling out from the “toe” of the levee freshens the salt marsh. “A little bit of freshwater marsh on the back side of the marsh is a good thing, but wholesale conversion could be detrimental,” he says.

Also unlike Oro Loma, this levee won’t get watered year round. Lindley designed the irrigation and filtration system to mimic local hydrology – with more water on the plants in winter and spring than summer and fall. “We’re tuning flows to the plant species we want, rather than to wastewater treatment goals,” he says, happy to see horizontal levees inspiring a broader vision of benefits.

Conceptual design for Palo Alto horizontal levee, reflecting a phased approach while the U.S. Army Corps and the San Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Agency plan a larger bayfront flood control levee in the area (hence the wide offset from Harbor Road). Image: ESA.

One of the biggest possible projects, in terms of scale, could be a five-mile levee proposed between Castro Cove and Point Pinole in the East Bay. At its heart is a 3,700-foot stretch reaching from Wildcat Creek to San Pablo Creek and designed to create transitional habitat and protect the West Contra Costa sewage plant from flooding. The bigger footprint will require relationship-building with local property owners and community interests the county is not shying away from. A local group called the Watershed Project will take on some of this critical community outreach and eco-literacy work. “We have the place, the partners, the money, and expertise all lined up to take a crack at it,” says Josh Bradt.

Getting to this point in North Richmond hasn’t been easy. The Estuary Partnership’s work with local interests on a shoreline vision, leadership from Supervisor John Gioia, funding from the SF Bay Restoration Authority, inspiration from a Resilient by Design Bay Area Challenge project in the area, plus an active and engaged North Richmond community, all paved the way for progress.

Even more ambitious among the slate of pending horizontal levee projects may be “the First Mile” levee. Sandwiched between the hard edge of the Union Pacific Railroad and the Hayward marshes, just inland of which sit homes, industries, and utilities at risk from future flooding, this project will test everyone’s mettle to get it built.

But that’s the point. Nature-based infrastructure proponents need to test the regulatory waters for bigger, more ambitious projects involving bay fill or building within wetlands. Traditionally, this would be a major no no in terms of protecting endangered species and habitats. Permitting in the past, for anything in the bay zone, can be onerous at best and at worst, expensive quicksand.

“It’s hard to hold onto our champions, because these multi-benefit projects are risky, involve multiple partners, are hard to permit and fund, and take forever to implement,” says the Estuary Partnership’s Heidi Nutters, who runs a new collaborative of practitioners of nature-based infrastructure projects designed to help them forge on. “Our goal is to learn across projects.”

Nutters hopes navigating the First Mile project will lead to learning leaps. Project developers shared conceptual ideas with a new interagency integration team of regulators (aka the BRRIT) much earlier than in the past, for example, hoping to overcome possible barriers before spending a lot of time and money on design. “Regulators are more willing to come to the table and grapple with uncertainty together now,” observes Nutters.

Oro Loma site in August 2021. Photo: ESA.

And while all these new levees percolate along, stalled by pandemic inertia but now regrouping, the experiments at Oro Loma continue. “We see it as a living laboratory where we research management questions about horizontal levees that are important to the region,” says Nutters.

Oro Loma’s levee is really just a slope of dirt and plants with an elaborate filtration and water system designed to test different things, and never connected to the Bay or a marsh. Early tests revealed running wastewater through the slope removed more than 90% of the nitrogen in it, a big plus for water quality. Another result, however, has been that it was difficult to pass a large volume of wastewater through the levee system.

Since that means it could be challenging to scale for that purpose, Oro Loma managers are looking next to tougher treatment challenges, like what to do with the waste byproduct of reverse osmosis process used to recycle and purify wastewater. With drought and climate change taking water managers beyond the limits of existing supplies, water recycling to drinking water purity is becoming a must for California. For several years now, Valley Water has been trucking in the residue from its state-of-the-art Silicon Valley Purification Plant to tiny Oro Loma. Early results suggest promising removal of bad actors.

Though it has no horizontal levee, another project in San Leandro is following Oro Loma’s lead on nature-based water quality treatment with a proposed 7-acre treatment wetland capable of filtering about 20% of San Leandro’s wastewater. About 30% of the treatment plants in the region have some capacity to deploy nature-based solutions for wastewater treatment, according to recent research. San Leandro’s treatment marsh is 100% designed and approved, just weeks ago, by water quality regulators. “It’s a novel approach to our water quality challenges,” says Ian Wren, a consultant working to evaluate nature-based solutions in the region.

Save the Bay plants a habitat transition zone, another label for a wedge of dirt and vegetation aimed at adapting to sea level rise, at the Ravenswood complex of the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project near Menlo Park. At this time, the project has more than eight such zones (ranging from 20:1-40:1 slopes) in some stage of being built. Photo: Ivan Parr.

That’s not the end of the horizontal levee story around the Bay, however. Blueprints for a wide variety of planned shoreline adaptations now feature these humps of dirt, whether to protect low-lying stretches of Bay Trail, roadway or parkland. Marshes can only buffer some areas, and last so long, before they themselves succumb to the ocean’s advance to our shores.

“We’re going to have to have seawalls, but around and between them can be more natural transitional solutions, because plants and animals will need to retreat, just as we will,” says Bradt.

More

- Nudging Natural Magic (Estuary News December 2017)

- North Richmond Transitions (Estuary News March 2018)

- The horizontal levee: a multi-benefit nature-based treatment system that improves water quality and protects coastal levees (Science Direct 2020)

- Use of stable nitrogen isotopes to track plant uptake of nitrogen in a nature-based treatment system (Science Direct, 2020)