Making Shade Where There Isn’t Any

Photo: KDI.

FULL READ

Making Shade Where There Isn’t Any

During a typical day at work in the eastern Coachella Valley’s agricultural fields, Silvestre Caixba struggles to find relief from the desert heat. As he walks along different fields to provide maintenance for the irrigation systems, there’s little opportunity for shade or other ways to cool down.

Caixba’s day-to-day life outside of work is not much different. In the summer, when temperatures can reach more than 120 degrees Fahrenheit, the lack of shade in this part of Southern California makes the most common of outside tasks particularly arduous.

“Even at markets and shopping centers, there’s little access to shade. Most parking lots have nothing to cover us or the cars,” Caixba explains in Spanish. “It’s very difficult because the only moment you’re cool is while you’re inside the store. Once you’re back outside, you have to hurry to your car for the air conditioning.”

Photo: Maria Sestito

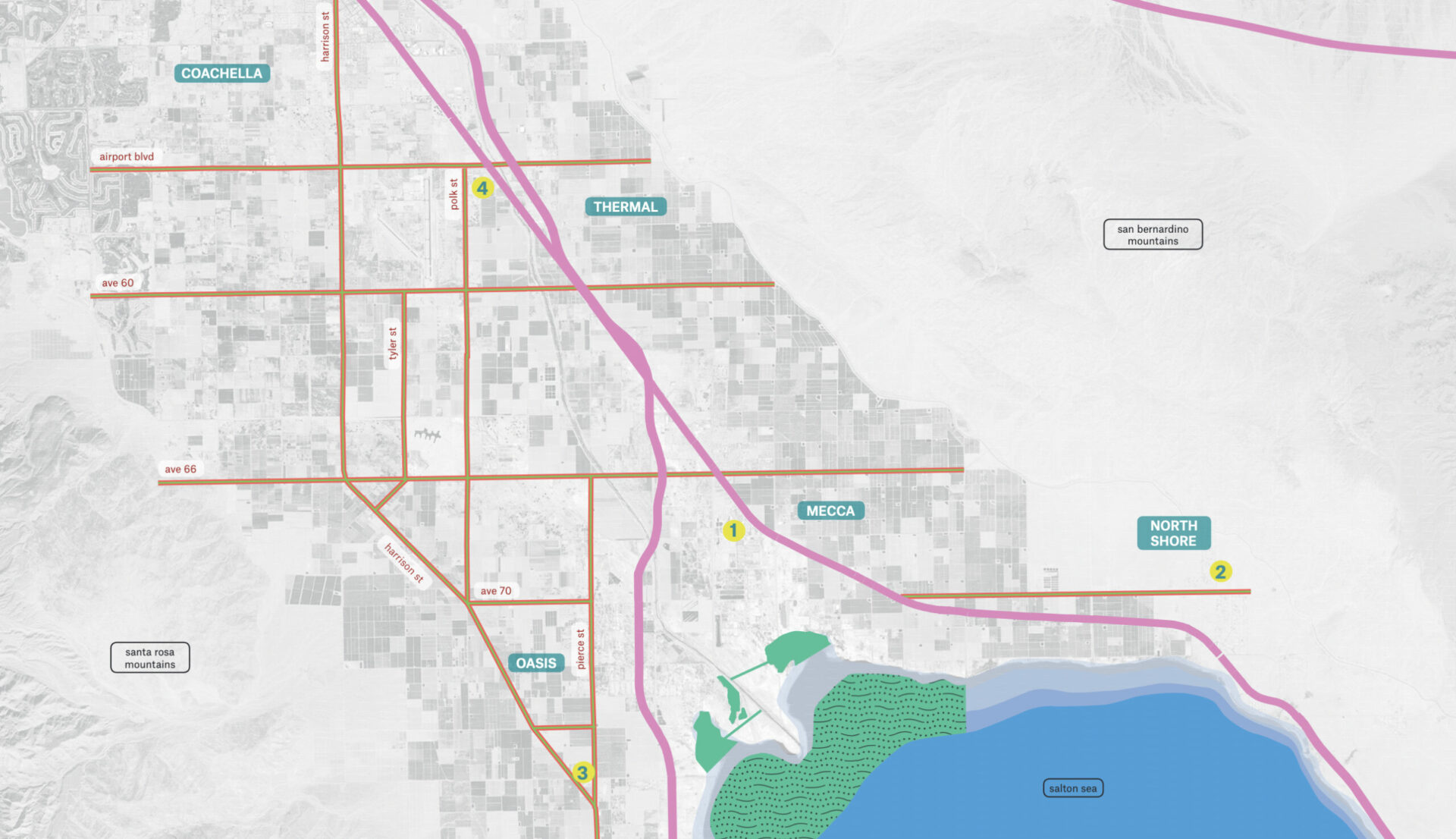

Caixba works throughout Thermal, Mecca and Oasis — unincorporated communities in Riverside County, which also includes the town of North Shore.

All four towns are small, according to 2020 Census Bureau data, with populations of slightly over 2,500 people each in Oasis and North Shore, a population of 1,371 in Thermal and 5,541 people in Mecca.

Although Caixba, 47, has lived in the area for half of his life, he says he hasn’t gotten used to the extreme heat.

“Only God knows how the body withstands so much heat some days,” he says, half-joking. “In this part of the valley, we don’t have a lot of services, including those that address how hot it can get,” he adds.

EXTREMES-IN-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Series Home

Click here to enter

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

Silvestre Caixba. Photo: Maria Sestito

Caixba tries to stay informed and be supportive of expanding services within his community when plans do arise. He attended the meetings that helped shape Oasis Del Desierto, a park that was supposed to be finalized in 2021, but still has sections under construction. He’s also been present at meetings in which county leaders spoke about establishing bike lanes and pedestrian pathways in Oasis, but has yet to see these materialize, he says.

“I’m not sure when we’ll see [bike lanes] in this area and even then, we would need more trees to help us with the heat,” Caixba says.

On the other side

Made up of mostly dusty land within the dry, open desert, the eastern Coachella Valley’s unincorporated areas lack public green spaces and overall protection from the sun that would allow people to spend more time outside.

That is in stark contrast to the amenities and public infrastructure — the “services” that Caixba refers to — available on the west end of the valley, about a 40 minute drive away.

The city of Palm Springs, for instance, is a busy tourist destination, home to luxury spas, golf resorts and even the Kardashians (at times), while many people in Thermal, Mecca, Oasis and North Shore can barely access the basics. In these east valley towns, thousands of residents have struggled for decades with contaminated water and routine power outages resulting from the absense of proper water mains and faulty power lines, on top of the limited parks and shade structures.

For over two years, the Oasis Leadership Committee, made up of community members, has been working with the Kounkuey Design Initiative, a nonprofit dedicated to community development and design, and with the Luskin Center for Innovation at the University of California Los Angeles to develop a study on the impact of heat issues in the unincorporated areas.

Eastern Coachella Valley, where Kounkuey is working with the community on where to focus shade-building efforts. Map: KDI.

The study also aims to find possible solutions, with a focus on shade equity.

“A place that experiences a lot of extreme heat — and really needs infrastructure — is where our particular kind of work can hopefully be useful to the people there, who are already advocating and planning around this stuff,” says Ruth Engel, an environmental data science project manager at the Luskin Center who joined the study nearly a year ago.

Meanwhile, the Oasis Leadership Committee and KDI meet regularly in the east valley to talk about new heat priorities. This summer was so hot, however, that it was hard for the groups to find a comfortable meeting space, and their meetings were postponed.

When they finally met again in September, rather than heat, the groups discussed flood damage from Tropical Storm Hilary the previous month.

The storm flooded some streets and destroyed already vulnerable infrastructure in the east valley. It also highlighted the wide range of preparation needed to address climate change issues.

In Hilary’s path was a colorful, wooden bench and shade structure that had been placed at a bus stop in Oasis in late 2022.

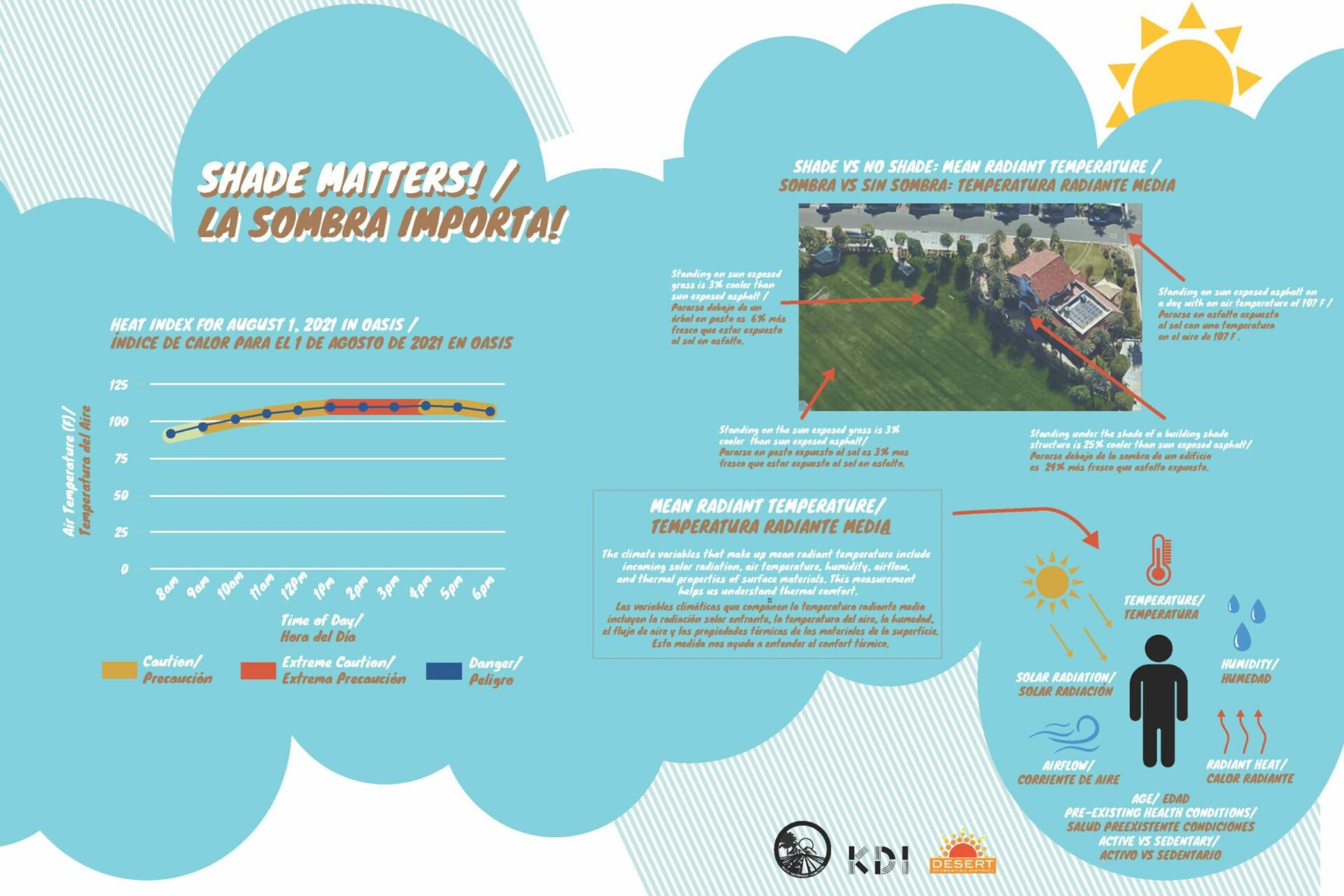

Engel says the shade structure was a result of the study so far, which found a lack of shade throughout the town’s bus stop route. No shade there potentially discourages residents from using public transit and makes their wait time dangerous.

This pilot project remained at the Oasis bus stop past its intended month-long demonstration and was removed once the storm damaged it, in August. Currently, it’s at Oasis Del Desierto Park but no longer seems safe to sit on, as wooden spikes stick out around it from the cracks it endured.

Community members and KDI were able to work with SunLine, the company that operates the local buses, to establish the shade structure. Partnerships like those facilitate such projects to see what can be set up more permanently in the future, Engel says.

The study has also shown that at Mountain View Estates, the mobile home park in Thermal where Caixba lives, and around various mobile homes in Oasis, there is “basically zero shade in the middle of the day,” Engel says. In the mid-afternoon (about 4 p.m.) these spaces are only shaded at 10 to 13%.

“At the very, very most, there’s about 14 or 15% shade, at like 8 a.m.,” she says.

The study doesn’t take into account “informal shade structures,” Engel notes, like canopies and tarps that residents set up themselves. Instead, it records shade from trees, buildings and other “formalized and public infrastructure.”

A woman sits in the shade while holding a yard sale along 70th Avenue in Thermal in September 2023. Photo: Maria Sestito.

Designing shade

To tackle the lack of shade, the groups involved in the study are working on a master plan that originally set out to assist Oasis but evolved to include all four unincorporated communities once data showed shared issues across the board. KDI is responsible for coming up with designs.

“The data that’s coming back about how much shade is available at certain intervals of the day is quite alarming,” says Christian Rodriguez, senior community associate at KDI. “Our master plan is going to take a look at already available data. And then, we’re also going to produce new studies and create an assessment of how to best address this sort of ‘shade desert,’ looking at both natural and built intervention.”

While planting trees is the obvious “natural intervention,” Rodriguez says building and structure designs, which consider the different times of day shade is most scarce and the height that would be needed to provide adequate protection, are examples of what’s to be built.

Dried mud, likely leftover from Tropical Storm Hilary, cracked from the heat in Thermal. Photo: Maria Sestito.

According to Engel, field work within the study has been funded by the California Strategic Growth Council, while the master plan layout is being funded by the state’s Governor’s Office of Planning and Research through a $685,000 grant for climate adaptation provided in 2023.

Once the plan solidifies, Rodriguez says KDI will submit it to Riverside County’s Executive Office, which will help facilitate participation across county departments for the implementation of new shade in the unincorporated areas.

Apart from the relief it could provide local residents, Engel emphasizes the significance of the study and resulting master plan beyond the valley.

“There’s never been a non-urban shade master plan. And because it’s such an effective way of relieving the physical health burden of heat, it means that the eastern Coachella Valley is really at the forefront of planning around this stuff … What we’re hoping is that this will give both a baseline and a sense of what’s possible, and allow the work to continue in a way [that’s] beneficial in other areas,” she says.

Engel pinpoints similar heat studies in the cities of Phoenix and Tel Aviv.

Experts on heat

Both Rodriguez and Engel underscore the importance of having the Oasis Leadership Committee’s participation, which allows for more input from residents of the unincorporated towns, who ultimately know best what lessens or exacerbates heat there.

From the governor’s office grant, $60,000 will fund outreach work done by community members.

“If there’s a really hot place, but no one’s there, it doesn’t matter that much. Or at least, it doesn’t matter from a health perspective,” Engel explains. For that reason, the study needs to include resident’s “expertise about how the community is used and how heat is experienced there,” she says.

Oasis Leadership Committee members share recognitions from their elected officials for their advocacy and participation in the Heat Impacts Study in Oasis at a ribbon cutting in 2022. Photo: KDI.

After 23 years in the eastern Coachella Valley, Caixba is one of those expert residents. He says most years, the heat starts increasing in June, with mid-July being the hottest it gets, with temperatures ranging from 117 to 122 degrees. Once October hits, the temperature begins to simmer down, he adds.

In the hotter months, Caixba says agriculture field supervisors allow workers to leave early if they start to feel unwell under the sun.

Though he hasn’t personally experienced some of the physical ailments that can result from extreme heat — dehydration, dizziness, migraines, fainting — Caixba says every summer, he does struggle with feeling stuck at home as there’s no way to be outside and cool at the same time.

“You feel stir crazy and you have to keep reminding yourself, ‘It’ll pass. It’ll pass,’” he says.

EXTREMES-IN-3D

SERIES CREDITS

Managing Editor: Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Web Story Design: Vanessa Lee & Tony Hale

Science advisors: Alexander Gershunov, Patrick Barnard, Richelle Tanner

Series supported by the CO2 Foundation.

Special Credits for Making Shade Where There Isn’t Any

Banner Image: Maria Sestito