Marshes Could Save Bay Area Half a Billion Dollars in Floods

What, precisely, is the value of habitat restoration? While answers tend to aim for pristine nature and thriving wildlife, one approach — recently published in the journal Nature — has assigned salt marsh restoration projects a dollar value in terms of human assets protected from climate change driven flooding. This novel approach uses the same models engineers use to evaluate the value of “gray” solutions such as levees and seawalls.

“You can really compare apples to apples when you put these green climate adaptation solutions on the same playing field as gray infrastructure,” says Rae Taylor-Burns, a postdoctoral fellow with UC Santa Cruz’s Center for Coastal Climate Resilience and lead author of the study.

Given that sea level is expected to rise by 1.6 to 7.2 feet (0.5 to 2.2 meters) by 2100, such value assessments are going to become increasingly relevant to the large population living and working near the low-lying shorelines of the San Francisco Bay Area. The region has already seen significant damage from floods when combined with high tides and storm surges. Statewide, if sea level rise reaches more than seven feet (2 meters), 675,000 people and $250 billion in property will be exposed to flood risk in the event of a 100-year storm.

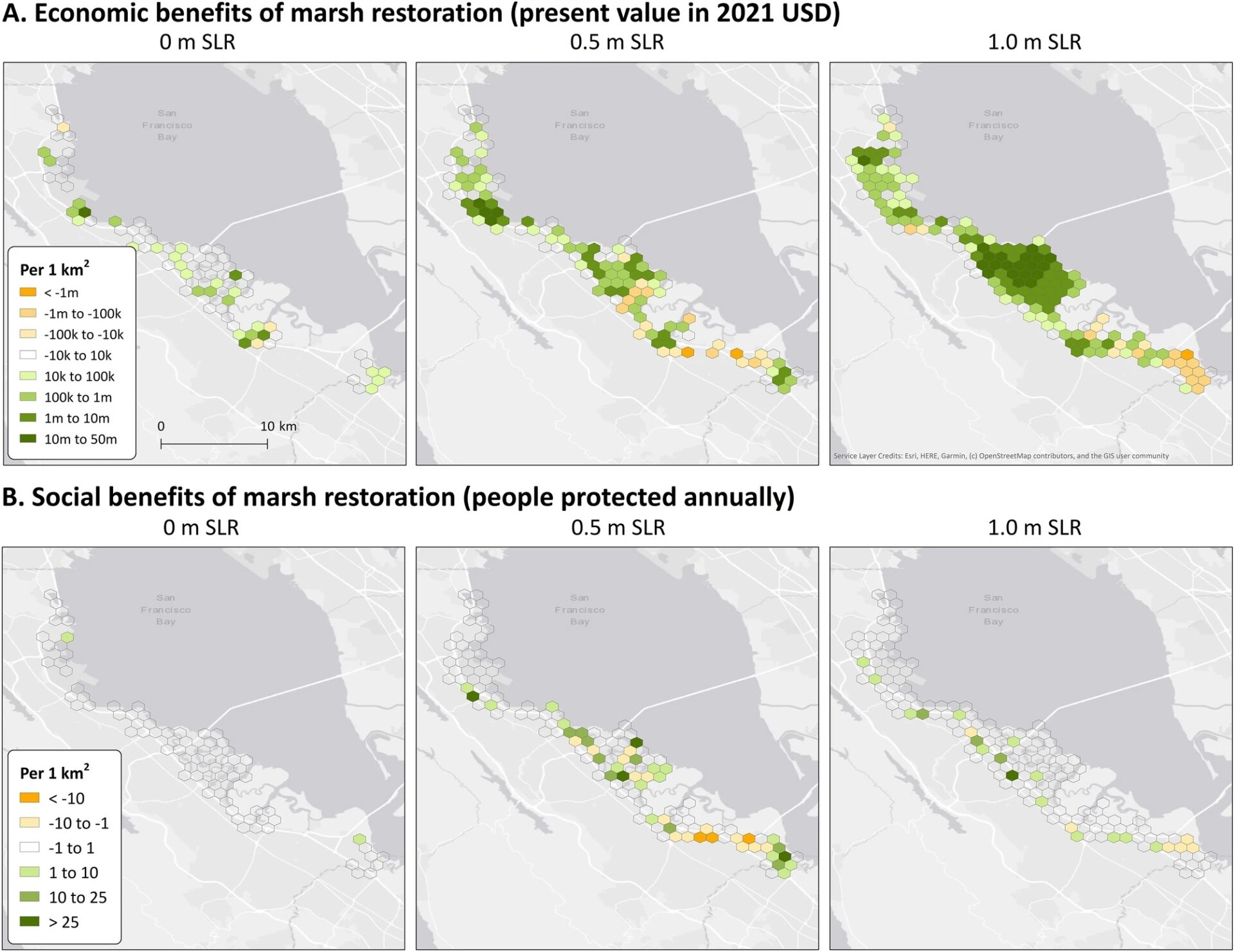

Map of (A) economic and (B) social benefits from flood reduction of marsh restoration with sea level rise. Green colors represent positive present value and people protected and orange colors show negative present value and increased risk. Source: UC Santa Cruz

Other Recent Posts

Assistant Editor Job Announcement

Part time freelance job opening with Bay Area climate resilience magazine.

Training 18 New Community Leaders in a Resilience Hot Spot

A June 7 event minted 18 new community leaders now better-equipped to care for Suisun City and Fairfield through pollution, heat, smoke, and high water.

Mayor Pushes Suisun City To Do Better

Mayor Alma Hernandez has devoted herself to preparing her community for a warming world.

The Path to a Just Transition for Benicia’s Refinery Workers

As Valero prepares to shutter its Benicia oil refinery, 400 jobs hang in the balance. Can California ensure a just transition for fossil fuel workers?

Ecologist Finds Art in Restoring Levees

In Sacramento, an artist-ecologist brings California’s native species to life – through art, and through fish-friendly levee restoration.

New Metrics on Hybrid Gray-Green Levees

UC Santa Cruz research project investigates how horizontal “living levees” can cut flood risk.

Community Editor Job Announcement

Part time freelance job opening with Bay Area climate resilience magazine.

Being Bike-Friendly is Gateway to Climate Advocacy

Four Bay Area cyclists push for better city infrastructure.

Can Colgan Creek Do It All? Santa Rosa Reimagines Flood Control

A restoration project blends old-school flood control with modern green infrastructure. Is this how California can manage runoff from future megastorms?

San Francisco Youth Explore Flood Risk on Home Turf

At the Shoreline Leadership Academy, high school students learn about sea level rise through hands-on tours and community projects.

The Bay Area filled or destroyed the majority of its 190,000 acres of historic tidal wetlands — natural buffers against waves, storms and sea level rise — over the last 200 years, with only 40,000 acres remaining by the 1990s. In recent decades, the region’s marsh extent has crept back up to 80,000 acres thanks to modern restoration projects (with 24,000 acres of additional restoration projects in the pipeline). Much of the region’s highly urbanized shore depends on complex gray infrastructure like levees, dikes, seawalls, and seawater pumping for flood protection.

However, according to Taylor-Burns, the current value of marsh restoration within her study area of San Mateo County is $21 million. Under current conditions, nearly half of the people benefiting from flood reduction due to restoration live in socially vulnerable census areas, the UC Santa Cruz paper stated. However that percentage would decrease as sea levels rise and the vulnerable are displaced — as the low-lying areas would be inundated, and the floodplain would expand into higher elevations and more affluent census blocks.

As sea levels rise, so do the financial benefits of marsh restoration: to over $100 million under conservative estimates of 1.6 feet (0.5 m) of sea level rise, and up to roughly $500 million given moderate 3.3 feet (1 m). Financial benefits are calculated by Taylor-Burns’ team using the input of a variety of local planners and government stakeholders. They utilized hydrodynamic models to determine flood depths and extents, and then used census and building stock data to determine the impact of the flood in dollar amounts and in terms of people impacted. Countywide, the flood reduction benefits of salt marsh restoration would increase by a factor of 23 given 1.0 m of sea level rise.

Taylor-Burns says the evaluation of benefits is likely conservative, because it did not consider co-benefits to the restoration — such as positive impacts on recreation or water quality, the paper notes. Likewise, it did not consider benefits to endangered species.

“If you think about quality habitat for animals, that is likely to be large expanses where they can be separate from the built environment,” Taylor-Burns says. “The restoration that could benefit endangered species might not be in the same place as those that would provide the greatest flood risk reduction.”

South Bay salt pond restoration project site near shoreline development. Photo: David Hasling

Even in terms of dollars, some restoration projects would deliver even higher benefits, based on what infrastructure is nearby — such as the narrow fringe of restored marsh near the San Francisco Airport which provides a present value of $900,000 per hectare.

“Small restorations that are adjacent to, say, a Google campus or densely developed suburbia would offer more risk reduction benefits than larger island restorations,” Taylor-Burns says. “But in a nutshell, the findings show that marsh restoration can play a role in reducing flood risk in the bay pretty substantially.”