Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Unpacking the Hold Up on Heat Protection for Indoor Workers

Mauricio Juarez recalls when the kitchen temperature in the San Diego County Jack-in-the-Box where he works reached 102 degrees Fahrenheit. Employees passed out from the heat and paramedics were called, but it took a workers’ strike to get managers to install an air-conditioner. Juarez was one of a long queue of indoor laborers who pleaded with the Standards Board of the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health to implement long-awaited rules, developed almost five years ago, to protect indoor workers from potentially lethal heat. While state leaders and legislators have voiced concern, meaningful action has been slow to come—a planned Cal/OSHA vote to determine if protections will become law won’t happen until early next year. Meanwhile, late summer temperatures remain high across the United States. “Heat is heat, and extreme heat is a threat to all workers who are subjected to it,” said Stephen Knight of Worksafe.

FULL READ

Unpacking the Hold Up on Heat Protection for Indoor Workers

Mauricio Juarez recalls when the kitchen temperature in the San Diego County Jack-in-the-Box where he works reached 102 degrees Fahrenheit. Employees passed out from the heat and paramedics were called, Juarez told a panel of state health officials in May, but it took a workers’ strike to get managers to install an air-conditioner.

“But it looks like they went for a cheaper remedy,” he said through a translator. “Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t.”

Robert Moreno, who works in a UPS warehouse, also made a public comment that day, telling the board that his workplace has “zero to no air flow” and routinely heats up to stifling temperatures.

“I don’t want to wait for someone to die for us to make changes,” he said.

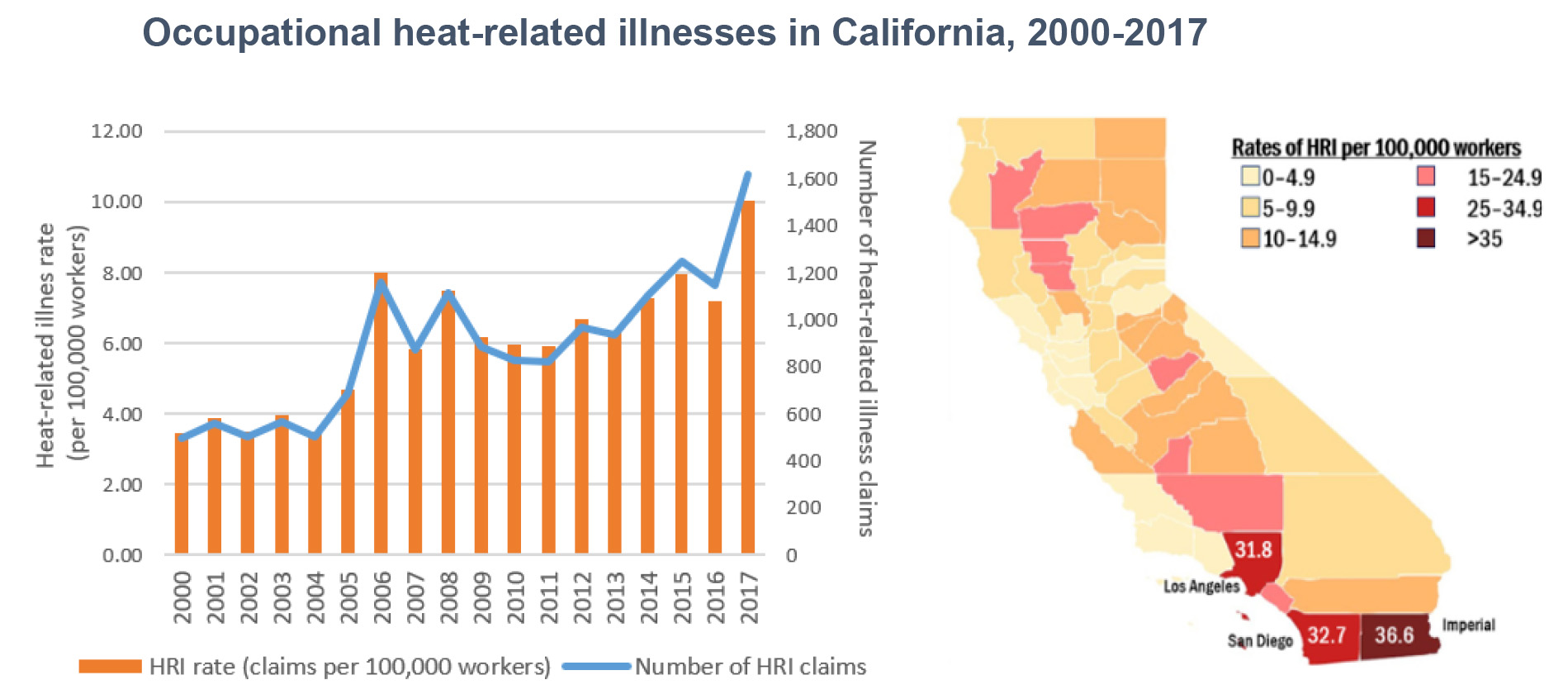

Juarez and Moreno were two of a long queue of indoor laborers who pleaded with the Standards Board of the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health, or Cal/OSHA, to implement long-awaited rules, developed almost five years ago, to protect indoor workers from potentially lethal heat. Existing protections, effective since 2006, only cover outdoor places of employment, like farms, highways, and construction sites. Business operations enclosed by walls and ceilings—places like warehouses, delivery vans, restaurant kitchens, and the cabins of grounded airlines—are essentially unregulated.

Stephen Knight, the executive director for the workers protection group Worksafe, says there isn’t a clear explanation for why indoor workers were left out of the 2006 regulations.

“Heat is heat, and extreme heat is a threat to all workers who are subjected to it,” he says.

Art: Alyson Wong. Original Photos I-Stock: coffeekai (workers); gorodenkoff (warehouse); cookelma (oven).

Heat protections for indoor workers have been years in the making. In 2016, Senate Bill 1167 became law, requiring that state officials create a heat illness and injury prevention plan by January 1, 2019. They did, missing the deadline by just a matter of weeks. The rules they produced, draft rules, if implemented, would protect workers in any indoor workplace where temperatures reach at least 82 degrees Fahrenheit, with specific remedies required when temperatures equal or exceed 87 degrees. But the bill did not require the plan to be implemented. These guidelines have remained frozen in regulatory limbo ever since they were published.

This lax action has almost certainly led to fatalities in the workplace. Louis Blumberg, senior climate policy advisor with the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center, says the number of Californians employed in the warehouse and storage industries since 2019 has increased by 50%.

“Given the heatwaves that are happening, the threat to these workers has increased exponentially,” he says.

The Standards Board has indicated it will “likely” vote on the rules in early 2024. In an emailed statement, the board said the new rules “would require engineering controls, administrative controls, and personal heat-protective equipment to protect workers” and, if adopted, would “go into effect” on July 1, 2024.

But Blumberg says that even if the guidelines become law early next year, standard administrative proceedings will prevent them from protecting workers until 2025.

Blumberg submitted written comments to the state asking that the rules be implemented as soon as possible and with the threshold for coverage lowered to 80 degrees, consistent with indoor worker protections in Oregon. Other advocates have suggested a 77-degree coverage threshold. The California Chamber of Commerce, meanwhile, has pushed in the opposite direction, asking state officials to apply the rules only to un-air-conditioned structures where the temperature reaches or surpasses 95 degrees. Those specifications would exclude air-conditioned vehicles that can heat up to 100 degrees or more—conditions described at the May hearing by delivery driver Heath Lopez. He said that “even the working air-conditioners in some of the vans” have little cooling effect on a hot day. Other delivery drivers complained of interior vehicle temperatures in the 140-degree range.

EXTREMES-IN-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Series Home

Click here to enter

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

Daniel Rivera, who sorts packages at a San Bernardino Amazon depot, told the board that he had suffered nosebleeds and other symptoms from heat stress on the job, as had multiple coworkers.

“It’s a cycle that’s not going to stop until we put a real standard in place,” Rivera said. “Another summer without these protections will put too many of us workers in danger.”

Summer came, and July went down as the planet’s hottest month ever recorded. 2023, in fact, is shaping up to be the hottest year on record, and with a strong El Niño developing 2024 could be hotter still.

Officials are, at least, paying attention. On Aug. 16, Gov. Gavin Newsom called on schools to remove on-site asphalt and plant more trees as a heat mitigation measure. The day before, Cal/OSHA issued a warning to employers to mind the safety of their workers ahead of a triple-digit August heatwave. On July 24, 112 members of Congress sent a letter to the U.S. Department of Labor warning of a “dire threat to the lives of workers exposed to extreme heat” and calling for “the fastest possible implementation” of a national heat standard to protect millions of people.

State officials with the Office of Planning and Research, the Department of Industrial Relations, and the Cal/OSHA Standards Board did not reply to emailed questions.

The Growing Risk from Indoor Heat

These calls to action are on point.

Heatwaves are not a new phenomenon, but global warming is making them more severe—that is, longer, hotter, and potentially deadlier, including for indoor workers. Michael Wehner, a senior scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory who studies extreme heat’s impacts on human health, says extreme heatwaves today are on average about 5 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than they would have been in the absence of anthropogenic climate change. This increase can easily spell the difference between life and death when it’s already 100 degrees or more—as it often is in enclosed, uninsulated workplaces.

“When it’s really hot, a little bit hotter makes it a lot more dangerous,” Wehner says.

Among all the disasters and weather conditions currently being aggravated by global warming, none kills more people than extreme heat, experts say, though these deaths are generally undercounted. They tend to be assigned to their more proximate causes like cardiac arrest, heart disease, renal failure, and various accidents caused by heat-induced physical and mental impairment. In 2021, the LA Times took up the task of tallying heat-related mortalities and estimated that heat kills an average of almost 400 Californians annually, which the reporters estimated was six times the official heat-related fatality rate.

Wehner notes that extreme heatwaves now occur roughly once every 20 years but that, by century’s end, they could strike every two years.

Of existing rules protecting workers, he says, “It’s appropriate for experts to reevaluate as temperatures increase and ask, ‘Are these laws appropriate for a new, warmer world?’”

Daniel Aldana Cohen, a U.C. Berkeley assistant professor of sociology, has studied the ways in which demographics and economics affect who is or isn’t exposed to dangerous heat levels. He says many lower-income Americans are unable to afford air-conditioning in their homes. If such people must also contend with workspaces that are not air-conditioned, they are more likely to fall ill or die during an extreme heatwave.

“If people can’t cool down at work, and they can’t cool down at home after work, that will cause far greater health problems and of course increase mortality,” he says.

California’s existing rules for outdoor workers are not always enforced, but they do at least offer clear guidance. They require that employers prepare a written plan of action to prevent and address heat illness and emergency response in the workplace. They also require employers to educate and train workers about risks and signs of heatstroke, provide “suitably cool” and complementary drinking water, provide and encourage rest and hydration breaks, and provide sufficient shade on days with temperatures higher than 80 degrees. Indoor protections are far more lenient, requiring only that employers, “correct unsafe conditions for workers created by heat as part of their Injury and Illness Prevention Program (IIPP).”

Taking Action and Blocking Progress

While state leaders and legislators have voiced concern, meaningful action has been slow to come. The May Cal/OSHA hearing was only the first public meeting to discuss the proposed indoor heat standard, four years after it was drafted. Early next year, a planned Cal/OSHA vote would determine whether it becomes law.

Other efforts to protect workers from heat are also slow-cooking on the legislative backburner. The Asuncion Valdivia Heat Illness and Fatality Prevention Act of 2021 was introduced in the U.S. Senate in April of 2021. It was read twice, then referred to a special committee, where it died. It was reintroduced in July 2023 as SB 2501 and is now idling under review. The bill, if someday passed, will require the Department of Labor to develop a system of standards to protect U.S. workers, both indoors and outdoors, from excessive heat. Among other things, the bill would protect whistle-blowers who call out employers for failing to ensure safe conditions.

In February, several state attorney generals, including California’s, petitioned the Department of Labor to implement an emergency temporary standard that would protect workers in both indoor and outdoor workspaces with rules that kick in when the heat index surpasses 80 degrees Fahrenheit. The petition fell dead at the feet of Assistant Labor Secretary Douglas Parker, who claimed in an April response that such emergency measures “would divert significant time and resources from developing a permanent standard and could very well result in no tangible results for workers.”

Knight feels progress on heat equity has been stalled and hindered by businesses and industries.

“Delay is really a product for the business community in the occupational health and safety world,” he says. “A delayed process is one that’s not subjecting them to any expense.”

In fact, business owners and representatives pushed back during the May hearing against the proposed heat standards for indoor workers, citing concerns over increased expenses and logistical challenges. They urged the board to relax and modify the regulations before implementation. As they’re proposed, several stated, the regulations create ambiguity about how and where they shall be enforced. Among other things, business leaders asked that the rules include an “incidental exposure exemption,” which would apply to workers exposed to high heat only momentarily.

Katie Davey, senior legislative director with the California Restaurant Association, told the board that requirements to keep kitchen workers cool could conflict with food safety rules that require animal products to be sufficiently cooked and subsequently maintained at protective temperatures.

Mitch Steiger, a senior legislative advocate for the California Labor Federation, asked the board to stall no more on protecting indoor workers from heat and to pass “ideally a stronger version of this standard.”

“God only knows how many workers have suffered and died because we’ve taken this long,” he said.

Cohen, at UC Berkeley, says passing rules protecting indoor workers will not mark the end of the fight. Employers, after all, must still abide by the regulations, and that doesn’t always happen: Researchers from UC Merced, though, interviewed farmworkers and reported in 2022 that existing rules for outdoor workers are met with “substantial non-compliance.” Among other things, the survey found that many employers failed to provide shade or monitor temperatures as required.

“Compliance,” Cohen said, “might be the next battleground.”

EXTREMES-IN-3D

SERIES CREDITS

Managing Editor: Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Web Story Design: Vanessa Lee & Tony Hale

Science advisors: Alexander Gershunov, Patrick Barnard, Richelle Tanner

Series supported by the CO2 Foundation.

Special Credits for Heat and Indoor Workers

Special thanks to Louis Blumberg and Bruce Riordan for background information and interviews.

Top Video: Tigerstrawberry, I-Stock