Tweaking Climate Talk So It Hits Home

Tanner with nudibranch, a “seaslug.”

Richelle Tanner is a special type of climate scientist. While many of the numbers she crunches come from satellites, rainfall records, or sensors in the oceans and ice, a lot of her data also come from people — and our perceptions about climate change.

Tanner is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Science & Policy at the Schmid College of Science and Technology at Chapman University in Orange, California. For the past seven years, she and her lab have been involved in several major studies exploring climate messaging. One study, published in 2021 and focused on the Gulf of Maine, tested how different metaphors can help Americans of all stripes both grasp information and act on it. According to the study, “Many standard communication strategies that rely on fear and scientific authority alone—rather than comprehensive explanations that include solutions—can leave audiences feeling overwhelmed and disengaged, instead of hopeful and motivated to act.” Tanner’s now involved in a much broader, national study on a similar topic.

“Everything we’re working on is based on trust and how to build it,” she says.

KneeDeep’s managing editor Ariel Rubissow Okamoto interviewed Richelle Tanner to get into the (figurative) weeds of how to research what makes a good metaphor, why grounding in shared values matters, and what makes climate extremes such a tricky aspect of climate science for non-experts to understand.

Q: Tell me about your new study.

The study is focused on the interaction between extreme weather events and climate change. These are phenomena like wildfires and hurricanes, and tornadoes and storm surge — things that you can’t directly attribute to climate change, but climate change plays a role in their unpredictability in the future.

Extreme weather events are confusing for people because they can be in what people perceive as the opposite direction of climate change. They can cool temporarily, or they can introduce more precipitation. The work we’re doing is trying to figure out how to communicate best that climate change increases the unpredictability of weather, not necessarily just creates a warmer, drier place all around the world. Because that’s just not true.

One entry point for approaching climate change topics is the value we all place on nature. Photo: Barbara Christianson

Other Recent Posts

Reforming Rules to Speed Adaptation

Bay Conservation and Development Commission to vote early this year on amendments designed to expedite approval of climate projects.

Warner Chabot Shifts Gears

After 11 years at the helm of the Bay Area’s leading science institute, its leader moves back into the zone of policy influence.

Is Brooklyn Basin Emblematic of Regional Development Vision?

The 64-acre waterfront development adds thousands of new housing units to one of the world’s most expensive places, but questions remain about its future.

Coordinate or Fall Short: The New Normal

Public officials and nonprofits say teaming up and pooling resources are vital strategies for success in a climate-changed world.

Pleasant Hill Gets Sustainable Street Improvements

An intersection redesign with safer bike lanes earned a national Complete Streets award, while sparking mixed reactions from drivers.

Six Months on the Community Reporting Beat

The magazine worked with four journalists in training from community colleges, and began building a stronger network in under covered communities.

Rio Vista Residents Talk Health and Air Quality

A Sustainable Solano community meeting dug into how gas wells, traffic, and other pollution sources affect local air and public health.

New Year Immerses Concord Residents in Flood Preparations

In Concord, winter rains and flood risks are pushed residents to prepare with sandbags, shifted commutes, and creek monitoring.

What You Need to Know About Artificial Turf

As the World Cup comes to the Bay Area, artificial turf is facing renewed scrutiny. Is it safe for players and the environment?

Threatened by Trump’s Policies, GreenLatinos Refuses to Back Down

National nonprofit GreenLatinos is advancing environmental equity and climate action amid immigration enforcement and policy rollbacks.

Q: So you’re trying to develop recommended language people can use for the kinds of extremes we’re experiencing?

We’re trying to explain extremes in a way that people find approachable, but has just enough background information so that they’re getting the proper scientific context, and that they’re not relying on unhelpful cultural models that they hold as bias.

Q: Can you give us an example of how this works?

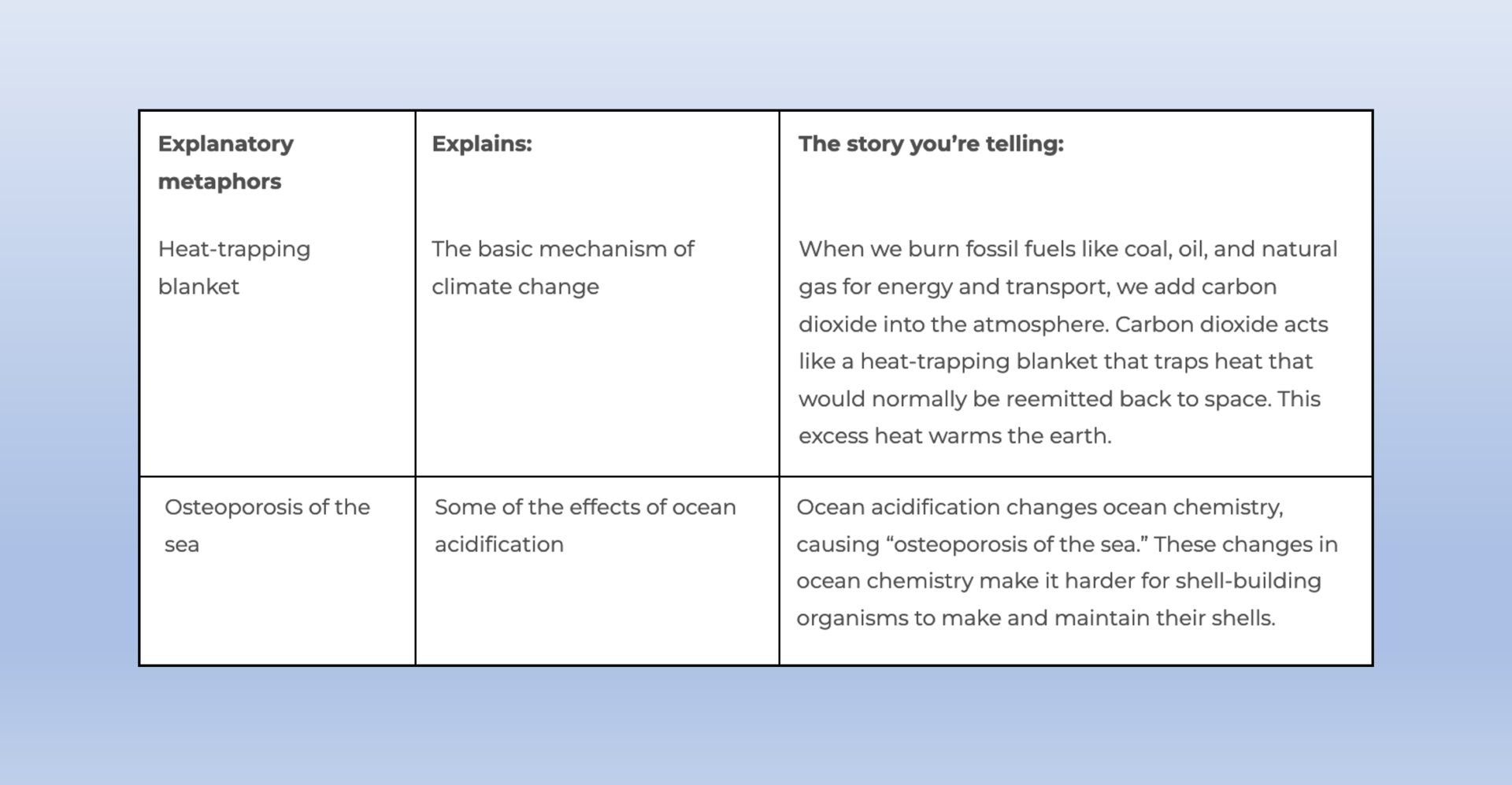

We spend a lot of effort evaluating cultural values in the public. The cultural values we hold that are related to the environment are the values of protection and responsible management. We all agree that it’s important to protect our natural environment, not just for the production of resources, but also for the intrinsic value of it — that it deserves to exist, outside of any value it can give to us. The other value is we all believe that it’s important to responsibly manage our resources.

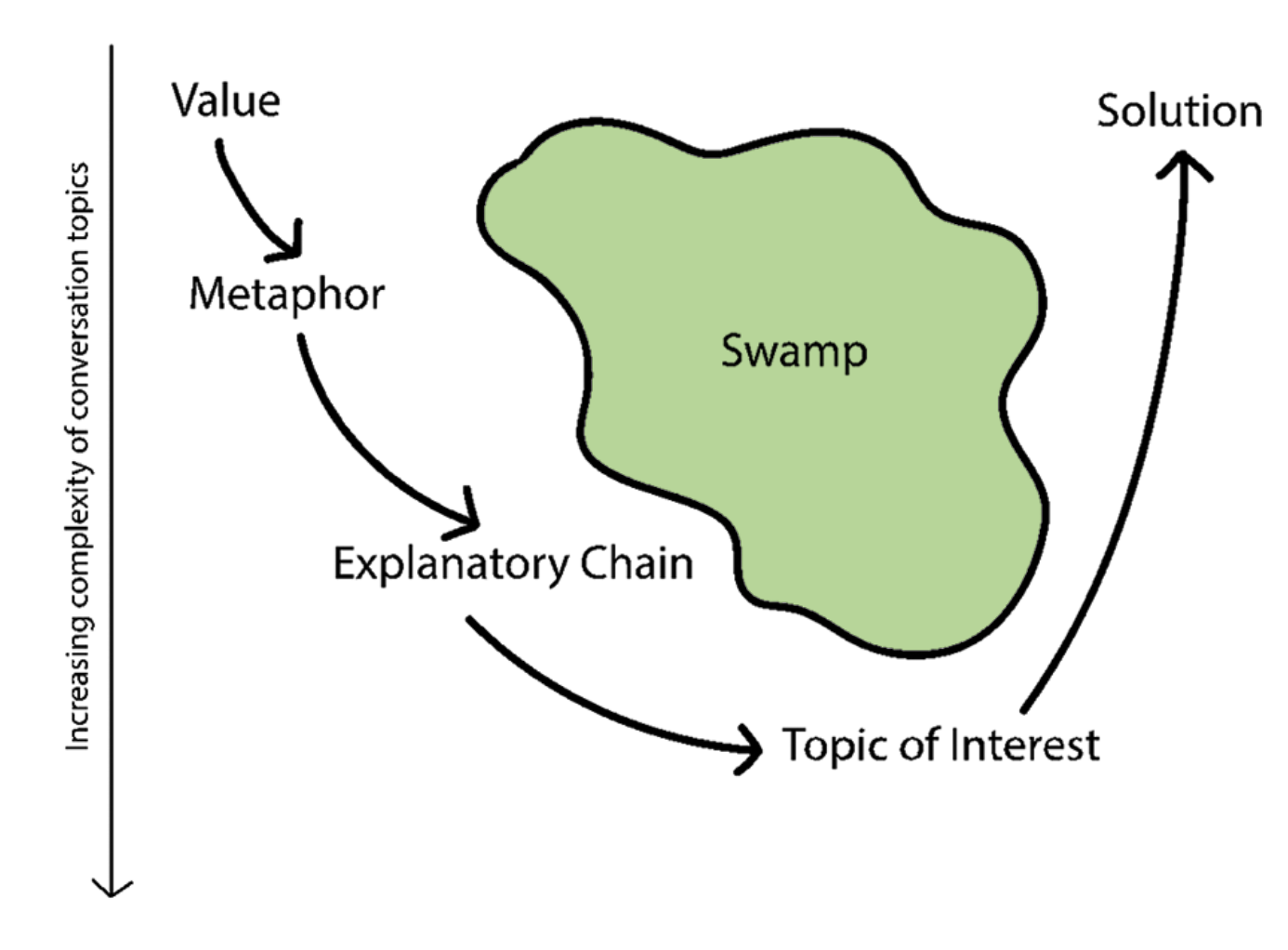

Navigating around the swamp of climate communication with hope-based tools. Source: Bonnono et al., 2021

When we build these communication pieces [for communicators to share], we not only develop them but also write them all out beforehand, and then memorize them until it feels natural. We always start with something like “it’s important to protect our natural environment” or “it’s important that we all responsibly manage our resources,” and it’s always framed as a “we” statement, not an “I” statement.

Our research shows that emphasizing individual action is not an effective way to communicate. It’s not your single responsibility to solve climate change, as the scale of the problem is massive and the scale of the solution also has to be massive. That’s why a lot of campaigns about recycling and turning off the lights and driving your bike to work have not been effective. People are not fooled by this idea that, “Oh, if you do one thing, everything will be okay” because they can see that the problem is very large, so we try to frame individual action as part of a community level solution.

So we go from connecting to people with a value, using a metaphor to explain a complex scientific problem, and then ending with this community level solution. That’s how we build our communication pieces, and it’s fairly effective.

Q: Do you have any metaphors for climate migration?

The language we use to talk about migrants and the language we use to talk about species that are overtaking ecosystems because we’ve introduced them is the same. It’s “invasive,” “illegal.” These language models are punitive and negative, but also place blame on the subject when the outcome is not necessarily their fault. When we say “invasive species,” it’s very active, like the species is trying to invade an area. It’s not. It’s just thriving in an environment in which it was placed, so even though I still use “invasive species” when I talk to science colleagues in biology and natural resource management, when we do our public presentations, we don’t say “invasive,” we say “introduced.” There’s research that shows that using “invasive” conjures up cultural models that make people think about “illegal” immigrants, which is a harmful way to talk about people and nature.

Q: What’s changed in climate science that makes communicating about extremes different?

I think 10–20 years ago, the science and the communication was really focused on a change in the average temperature and conditions moving forward. Now we’re a lot more concerned with outliers as a signal of change, so even in my physiology or ecology research, what we focus on is a change in the amount and the signature of variation in environmental conditions as our main problem in evaluating the effects of climate change. I think that’s pretty consistent across the field.

We’ve made this shift from people being really concerned about an average four degrees Celsius increase in temperature to being concerned about an increase in the stochasticity, which is the unpredictability of climate extremes with climate change. Because we’ve noticed that a lot of species can deal with this gradual change in temperature, but they cannot deal with the extremes that come along with it. The conditions when things are really hot, or really cold, or really salty or fresh like the water, whatever it is.

Q: Many of us learn about climate change through our news meteorologists, and their focus is always on warning people in time to be prepared. So the predictability of weather and climate is kind of baked into our approach. That raises lots of questions about how we shift our values?

I don’t think that this national study that we’re still finishing is going to have all the answers. It’s just going to be a start for how to broach a conversation about unpredictability.

It’s really hard to teach people that the scariest thing coming forward is that we don’t know what is going to happen. There are ways we can prepare for that, but we need to accept that we don’t know and that there’s no way to predict. That’s the signature that we are predicting — we are predicting unpredictability.

Tanner with her students embarking on conservation biology field trip to Catalina Island in Southern California. Photo: Richelle Tanner