Steve Rasmussen. Photo: Afsoon Razavi

One Man’s Five-Fire Learning Curve

Steve Rasmussen lives far enough into the wilderness around the Napa Valley that his phone bristles with apps. Apps that track everything from the weather to helicopter flight paths to fire flare ups. Why? Since he and his wife bought a 796-acre vineyard and woodland property in 2015, he’s been through five fires. The first was among the October 2017 wine country fires that consumed more than 100,000 acres. That year, California saw just how bad it could get when 80-mile-per-hour gusts, combined with fuel-heavy underbrush, drought and climate change, created four major fires spreading across two counties over three weeks. Rasmussen’s property, called Palisades Canyon, escaped one of those 2017 infernos, but he wasn’t so lucky three years later, when 90% of his acreage burned. In the last eight years, as PG&E and CAL FIRE have repeatedly staged operations on his property, he’s learned a lot about how to both collaborate with them and hold them accountable. And Napa County’s way of responding to fires, and building fire resilience, has also matured.

Extremes-in-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

FULL READ

One Man’s Five-Fire Learning Curve

Steve Rasmussen lives far enough into the wilderness around the Napa Valley, about a mile from the town of Calistoga, that his phone bristles with apps. Apps that track everything from the weather to helicopter flight paths to fire flare ups. Why? Since he and his wife bought the 796-acre vineyard and woodland property in 2015, he’s been through five fires.

The first was among the October 2017 wine country fires that consumed more than 100,000 acres. That year, California saw just how bad it could get when 80-mile-per-hour gusts, combined with fuel-heavy underbrush, drought and climate change, created four major fires spreading across two counties over three weeks. Most Napa Valley folks now refer to those 2017 infernos as “the wake-up call.”

Rasmussen’s property, called Palisades Canyon, escaped one of those 2017 infernos, the Tubbs Fire, but wasn’t so lucky three years later, when 90% of his acreage burned. So when the Pickett Fire flared up on Aug. 21, 2025, the brainy and bubbly 73-year-old vintner, and the county’s fire responders, were ready.

Barn roof line today mirrored in Glass Fire image on the phone. Photo: Afsoon Razavi

EXTREMES-IN-3D

A seven-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Series Home

Click here to enter

Part 6: Infrastructure

Part 7: Aftermath

Supported by the CO2 Foundation.

“I can see bombers dropping red retardant two canyons away from us,” he texted a friend when the Pickett Fire arrived. “Luckily the winds have been light and blowing away from our house and vineyard. Everyone is glued to the Watch Duty app.” The helicopters, fire engines, and bulldozers, what he called “the calvary,” arrived on his ridge soon thereafter.

None of this is anything new to Rasmussen, and he’s learned how to respond the hard way. Over the last eight years, PG&E and CAL FIRE have repeatedly staged operations on his property, wiping out and rebuilding roads, clearing brush and trees, and choreographing back-burns. On his end, he’s updated all six homes on his property to be as fire resistant as possible, built fire breaks and defensible space, and explored how to get grants to clean up post-fire messes.

But there’s one thing, a belief he has in common with another brainy guy on the Napa Valley fire scene, that is a key factor in their successes as modern day armchair and on-the-ground firefighters.

“If you act like a steward of your property, rather than building a fortress to keep everyone away, you start meeting your neighbors and working with other people. You start a community that buys into the whole idea of wildfire preparedness together,” says Rasmussen.

“Fire doesn’t really care if you’re rich or poor. It doesn’t care if you lean left or lean right. It doesn’t care about your parcel boundary or county border. Fire just moves based on three things: fuel, terrain, and weather. Because of that, wildfire resilience is a unifying thing,” says Joe Nordlinger, chief executive officer of the nonprofit Napa Firewise Foundation.

Joe Nordlinger (left) meeting with partners in the fire fight. Photo: Firewise

For both the individual and the collective, it helps that Napa County is small, affluent, and has a strong industry in its wines and vines. And it helps that Rasmussen himself has the resources, time, and chutzpah to do what’s necessary to continue to be a vintner in a fire-prone region and pay the insurance hikes.

And it helps that Nordlinger, too, had 23 years of experience as a CEO before he bought his own 28 acres of Napa wildland and took charge of Napa Firewise. Since then, he’s grown the organization into a centralized, well-resourced “mothership” of fire preparedness with 22 community-based fire councils, including one Rasmussen works with, and $50 million in grants.

“I believe in collaboration and coalition building more so than consensus. Consensus often leads to sub-optimal outcomes and the inefficient use of resources,” says Nordlinger, who points out that one key strategy for scaling Napa Firewise was to avoid having each fire council become its own nonprofit. “This way, the local councils can really focus more on community outreach, the connective tissue to the community, and not have to be out there chasing money.”

Nordlinger, like so many people in California now, has a first fire story. His was the Wragg Canyon Fire of 2014.

“I saw that strata cumulus of smoke on the horizon. And suddenly my 28 acres of forested land, which seemed so lovely, seemed very threatening,” he says.

Tubbs Fire, October 2017 ~ The Wake-Up Call

Rasmussen grew up on the East Coast and worked as a publisher of innovative mathematics materials, but it was his spouse, real estate investor Felicia Woytak, who had the money to buy several Napa Valley properties, of which Palisades Canyon is the jewel.

Their 796 acres, part of which is co-owned by a neighbor, rises from the Napa Valley floor to the ridges of volcanic red rock formations for which the property is named. The spread has six homes, 17 acres of vineyards, and 750+ acres of wildland and forest under a conservation easement. The couple now makes high-end Napa Valley wine.

Concrete water tanks store water for firefighting and irrigation. Photo: Afsoon Razavi

Tubbs was Rasmussen’s first fire. He and his wife didn’t evacuate, largely because they felt secure surrounded by vineyards — which don’t burn easily. They also had fire hoses and 30,000 gallons of water stored in tanks on the ridge that could use gravity to fight the fire.

“The real risk, with those damn winds, was a stray ember landing somewhere,” says Rasmussen. “If you are prepared, you can douse them.” The Tubbs Fire skirted his property but raced over the county border and down to Santa Rosa in what seemed like the blink of an eye, destroying 5,600 homes and ending 22 lives.

“I have a lot of friends that lost property, lost houses, in the Tubbs Fire, so it was a wake-up call. We started to double down on our preparations,” he says.

Doubling down meant hardening the property — clearing “defensible space” around the houses, improving fire hoses, retrofitting buildings with metal roofs and one-way Vulcan vents, and starting what would become a never-ending battle to clear brush, deadwood, and flammables from their forested acreage.

PG&E Canyon Fire 2018 ~ Too Many Trucks & Logos

Just a year later, a helicopter flying low sliced through the high voltage power lines of the canyon behind Rasmussen’s house. The power immediately went out in Calistoga and Middletown, and everywhere in between.

The snapped line, meanwhile, fell to the ground and sparked a fire in the canyon. Rasmussen’s wife saw the offending helicopter limp away to safety. It wasn’t long before first responders arrived: fire engines, more helicopters, even smoke jumpers. While they battled the fire, Rasmussen’s crew put out flare ups in the vineyard.

Water-dumping helicopter negotiates power lines during a Santa Cruz area fire. Photo: Steve Kuehl

“PG&E worked all night to put the high voltage wire back up,” says Rasmussen. But that wasn’t the end of it. In 2019, the wire snapped again.

“It was snaking around in wind. It almost touched our house,” he says, remarking how lucky they were that the wire wasn’t live, because the snap occurred during a power shut down to protect public safety (PSPS — an irritating but now familiar tactic to Californians after lawsuits against PG&E over the wine country fires).

Rasmussen started paying attention to how PG&E was doing fire prevention work on his property. He noticed it usually involved multiple contractors doing different things: one to cut limbs, one to chip wood, one to clear brush or “slash,” and more. There was a lot of coming and going of trucks with different logos and crews, and sometimes they didn’t clean up after themselves very well. A lot of his neighbors were frustrated, too.

“I realized understanding the system was a lot better than just making complaints or getting excited and hollering at people I knew weren’t decision makers. So when I helped crews go through my property, I always told them I’d tell the inspector what I thought of their work,” he says. “That got their attention and cooperation.”

Herbivores keep the dry grass and brush down in the canyon behind Rasmussen’s house, which he calls the “goat moat.” He regularly invites school groups up to visit with these sure-footed firefighters. Photo: Afsoon Razavi

When the high voltage wire snapped that second time, he discovered the broken ends were still visibly frayed and burned from the first snap. So when the PG&E crews next appeared to splice and restring the old wire, he told them he was going to keep a piece unless they repaired it properly.

“I figured if it fell again and burned down my house, I’d have the evidence to show their negligence had caused the fire,” he says. Not long afterward, all three high voltage wires across the canyon were swapped out with stronger, steel-core cable. Today, they have colored balls on them to make them more visible.

Kincade Fire 2019 – Forward Progress

Another fire in Rasmussen’s neck of the woods flared up in 2019 but stayed up around Mt. Saint Helena. He watched it like a hawk and checked his apps, but the wind never shifted in his direction.

Meanwhile he, like everyone else who’d gotten close to the 2017 fires, kept clearing brush and deadwood on his property, as did Joe Nordlinger on his 28-acre spread in the western foothills of the Napa Valley.

“I recognized you’re better off doing this work, and it’s expensive work, incrementally and making forward progress, than thinking you have to do it all at once,” says Nordlinger.

At the county level, in the years after the 2017 North Bay fires, lots of other things were in the works. Napa invested in a countywide wildfire protection plan with specific priorities, a process facilitated by Firewise and involving 32 agencies. The Napa Resource Conservation District, meanwhile, worked with the county to provide more technical assistance to landowners navigating post-fire recovery.

“Two of the biggest challenges for communities and fire safe councils that want to achieve sustained wildfire resilience are fragmentation and complacency,” says Nordlinger.

To combat this, Napa Firewise has undertaken more than 500 projects focused on three things: vegetation and fuel management around roads and at the landscape level; a valley stewards initiative; and what Nordlinder calls the “care and feeding” of Firewise’s 22 fire safe councils.

CAL FIRE’s heavy equipment for cutting fire breaks. Photo: Steve Rasmussen

At the same time, the Napa RCD joined its neighbors and other organizations in launching a North Bay Forest Improvement Program.

“In 2017, at the time of those first big fires, our RCD didn’t even have a forestry program,” reflects Ali Blodorn, who directs the district’s forest health initiatives. Before then, the district was more involved in helping landowners with soil and water conservation, as well as wildlife-friendly farming. “Now forest health and fire resilience are one of our biggest and most funded programs. I manage a grant that supports capacity building for Napa and five neighboring counties,” she says.

But all of these initiatives were only just beginning to make headway — the countywide plan had just been completed — when the Glass Fire torched 67,000 acres of wine country.

“It was a crystallizing moment,” says Nordlinger.

Glass Fire September 2020 – Command Positions

Calistoga is a sweetheart of a small American valley town, centered around a historic Main Street that mixes Wild West salons with artisan wine bars and mud baths. And it was this town of 5,000 at the north end of the Napa Valley that CAL FIRE was worried about when it took a stand on Rasmussen’s ranch during the Glass Fire.

The fire started seven miles south of his property, and soon, fed by hot Diablo winds, was behaving like “a blowtorch” on the nearby Calistoga Ranch property, according to a firefighter who fled the scene. The blaze quickly tripled in size and appeared on Rasmussen’s horizon.

“I took the CAL FIRE commanders up our roads so they could get way up high in the Palisades and close to the fire and see it. And that helped with planning,” he says.

Rasmussen makes a point of working with his neighbors to maintain half a dozen roads (both dirt and improved) so that access remains open, not only for the property owners but also for maintenance crews working in the adjacent state park and, of course, fire vehicles.

CAL FIRE soon sent four large bulldozers. The crew worked through the night to build a massive firebreak by widening one of the ridge roads. “The line didn’t hold. There was a lot of wind,” says Rasmussen.

These green-engines at Palisades Canyon during the Glass Fire belong to California’s strategically staged, at-ready CALOES fleet that any fire district can commandeer and use. Photo: Steve Rasmussen

The next morning, five fire engines and a prison crew from Sonora Fire Camp arrived. They worked in the woods and around the buildings to get ready for fire. Rasmussen and his wife practiced with fire hoses. “We brought all our neighbor’s tractors and dozers into the middle of the vineyard where they’d be safe. We gave shelter to some of our neighbors whose homes were more threatened,” he says.

Since the firebreak hadn’t held, and the winds could pick up again, CAL FIRE started worrying about the fire racing down the canyon into Calistoga. They decided to do a controlled back-burn.

“They didn’t tell us what they were doing, we just had to figure it out as they did it. We sat in the house watching them light fires all around us. They used our roads and trail systems to do it. The battalion chief sat up on the top of the hill, in the spot I had told him he could get the best view of the terrain, and choreographed an elaborate controlled burn across our entire canyon that unfolded in ways we didn’t expect,” he says.

Video from the night of the Glass Fire, as CAL FIRE set the back-burn in the woods around the main house. Video: Steve Rasmussen

Rasmussen later learned that part of this choreography included setting fire to a large ring around a house, and then starting another ring closer in. “When the first fire is roaring, it sucks oxygen and creates its own wind, drawing the second fire away from the house. I saw multiple instances where they would make one fire to attract or draw another. It gave me a lot of insight into how CAL FIRE thinks,” he says.

The battalion chief’s plan worked, saving the houses and vineyard infrastructure, keeping the fire at a low enough intensity to save trees, and using Palisades Canyon as a 750-acre firebreak to protect Calistoga.

“It was both miraculous and [sad], all that scorched ground. My wife couldn’t go up into the canyon for months. It was too depressing,” says Rasmussen. But in the immediate aftermath, he did go there to put food and water out for the animals in the blackened canyon. “I made a lot of friends among the bears,” he says.

In retrospect, he says, the Glass Fire helped him see how CAL FIRE operates from the inside and made him think about all the ways he could be more proactive.

“They can’t save everything, and the first thing CAL FIRE sees when looking at a rural property is what the homeowner has done. It’s totally obvious to them immediately whether you’ve done anything or not to protect your own property. If you haven’t done much, they’re not going to risk their lives to do it. But if what we do is recognized as beneficial by CAL FIRE, they’ll send more resources here,” he says.

Bankrolling Post-Fire Restoration

After the Glass Fire, Rasmussen joined Calistoga’s fire safe council and helped organize neighbors into the “Palisades Fire Watch.” He also started looking into what grants were available to clean up the burned woods and repair the fire roads. What he found was a can of worms.

The first likely grant fell under something called the EFRP, a federal disaster recovery assistance program administered by the USDA Farm Services Agency. At first glance, the program looked like a good fit, as it aimed to help landowners clean up after wildfires and hurricanes. But after some phone calls to local agencies, and even to U.S. Rep. Jared Huffman’s office, it looked like Rasmussen was ineligible. At the time, in 2020, the program had yet to deploy in California, and the nearest use was in Oregon, where the timber industry had helped themselves to program grants and become the local model for federal officials.

So Rasmussen did some homework: “I read the legislation and didn’t see anything in it that required I had a timber harvest.” Further research suggested the money was for agricultural landowners, not commercial interests. “I wrote letters and complained. I got in contact with FSA officials,” he says.

As the first grant stalled out, he went after a second to fix a road ruined by CAL FIRE in their efforts to bulldoze a firebreak. “They just ripped the top of our ridge off, and the road got ripped off with it,” he says.

Right away, he applied for an EQIP grant administered by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, got approved, and was able to fix the road by spring 2022. Under the grant, the NRCS reimbursed him for 60% of the projected cost ($44,571). “We did the tree work first, piling and burning all the burned wood within 25 feet of the road. We cleared selectively, aesthetically,” he says. He then rented a $4,000-a-week bulldozer and got a skilled friend to rebuild the road. Some tasks cost more than projected, and others less, always a challenge to document. But the process was much easier than the can of worms he opened trying to get his next grant, he says.

Fire road fixed with the EQIP grant. Photo: Steve Rasmussen

One day, a grower bulletin arrived in Rasmussen’s inbox announcing that landowners in the scar of the Glass Fire were now eligible for those federal emergency reforestation grants he’d been turned down for a year before. Seventy landowners in the fire scar applied. Rasmussen filled out applications with his two elderly neighbors as a group, using what he’d learned already to get the EQIP grant. “We’re a little canyon of old men, but we still get stuff done,” he says with a proud giggle.

In the process, he familiarized himself with the official rate sheets used by agencies to project reimbursement levels — covering more than 300 practices ranging from cutting down large trees to hauling or burning or chipping slash.

“It’s not just one category for trimming trees. It’s trimming big trees or little trees or medium-sized trees,” he says. “And for me and my neighbors in the Glass Fire burn scar, it’s also trimming trees in a steep, rugged canyon. I figured we’d need four times the amounts on the rate sheets for that.”

In time, Rasmussen became a spokesperson of sorts for his neighbors because he had experience with the grant process. After jumping through all the required hoops — site visits by RCD, property mapping, documentation, budgets — many landowners were underwhelmed with the bottomline. “When people heard how much money they were going to get, they’d just tell the agencies to go to hell,” he says.

Rasmussen worked with administrators to get the state’s fledgling FSA-EFRP grant program to use a different, more realistic California rate sheet to value the work. He then won an appeal to a local oversight committee to raise the reimbursement by 150% of the written rates to account for the rugged terrain in the fire area and for the high labor rates in Napa Valley.

He also learned how different practices on the rate sheets could be “stacked.” For some of the work, you get paid for three tasks on one acre or one tree, and for others not. “It gets complicated,” he says.

In general, for the 70 Glass Fire applicants, the grant process dragged on and on. The local FSA office was new to the job and understaffed. Meanwhile, there were 70 sets of property maps, forestry plans, environmental reports, cultural assessments, maps of spotted owl habitats, reimbursement calculations, and contracts to prepare for property owners before work could be authorized.

“The fire-weakened trees were falling and making the work harder. But we had to wait until we got approval before beginning, otherwise we would not get compensated,” he says.

Eventually, he and his immediate neighbors were approved for five grants totaling more than $300,000 to work on their canyon properties over two years starting in 2024. Various restrictions narrowed the window to do the work to as few as three months during the year.

Rasmussen is still trying to get the work done before the grant period ends. “I bit off more than I can chew. But I don’t have to do everything on the grant list. I can choose to do what is most strategic and get paid for the things I do,” he says. Rasmussen says he appreciates how hard the FSA staff have worked to bootstrap the program.

A bridge Rasmussen built out of fire-damaged wood. Photo: Afsoon Razavi

Not everyone was as patient. Other property owners went ahead with work without waiting for official approval and then got red-tagged by the county.

“It’s gotten kind of ridiculous, because on the one hand, CAL FIRE is out there in our woods bulldozing and blading and flailing with a masticator to make our community safe. And the county encourages CAL FIRE to do that,” he says. “But when a private landowner cleans up after the fire, they can get in trouble.”

Rasmussen understands the need to be careful with the wild, but the old county rules no longer seem to fit the new normal. “I’m an environmentalist. I don’t want to clear cut forests. I don’t want to damage trees or streams. I want to keep all the oak trees I can. But the county conservation and land use laws we have to adhere to did not account for this level of destruction by fire,” he says.

“It’s better to disrupt the landscape in minor ways, than to not do [any fire prevention at all],” Firewise’s Nordlinger points out. “Because when fire does come, it’s likely to be super catastrophic and really nuke these ecosystems in ways that they’re just not going to be able to recover from. We need to help these forests be resilient to what will eventually come.”

Pickett Fire September 2025 ~ Can Do Community

This fall, a vintner prepping for a wedding apparently caused a fire that brought CAL FIRE to Rasmussen’s canyon again. By then, he had spent a quarter of a million of his own money on fire clean up and preparedness.

But the county’s four fire districts, Firewise, CAL FIRE, and landowners are all so much more organized and experienced with managing wildfires in this specific terrain now, and so much more work has been done to clear fuel and build fire breaks, that the last two fires didn’t bring about as much devastation as their predecessors.

“They held the Toll Fire to 40 acres using a fuel break we had built with vintner donations as a fallback containment line. It totally made a difference,” says Nordlinger. “The same thing with the Pickett Fire this September. It was devastating and unfortunate for some, but work that we had done in advance with the Napa Land Trust contained that fire.”

The RCD’s Blodorn agrees. Post Pickett, she’s had the opportunity to see how fire interacted with landscapes that had gotten some attention to resilience. “Things look really good in areas with previous thinning and fuel reduction projects. It’s really encouraging,” she says. “It’s a good reminder that the investments that landowners are making really do pay off. The trees are looking good, and no fire is getting up into the canopy.” (Indeed, data confirm that the fire produced only low to moderate burn severity).

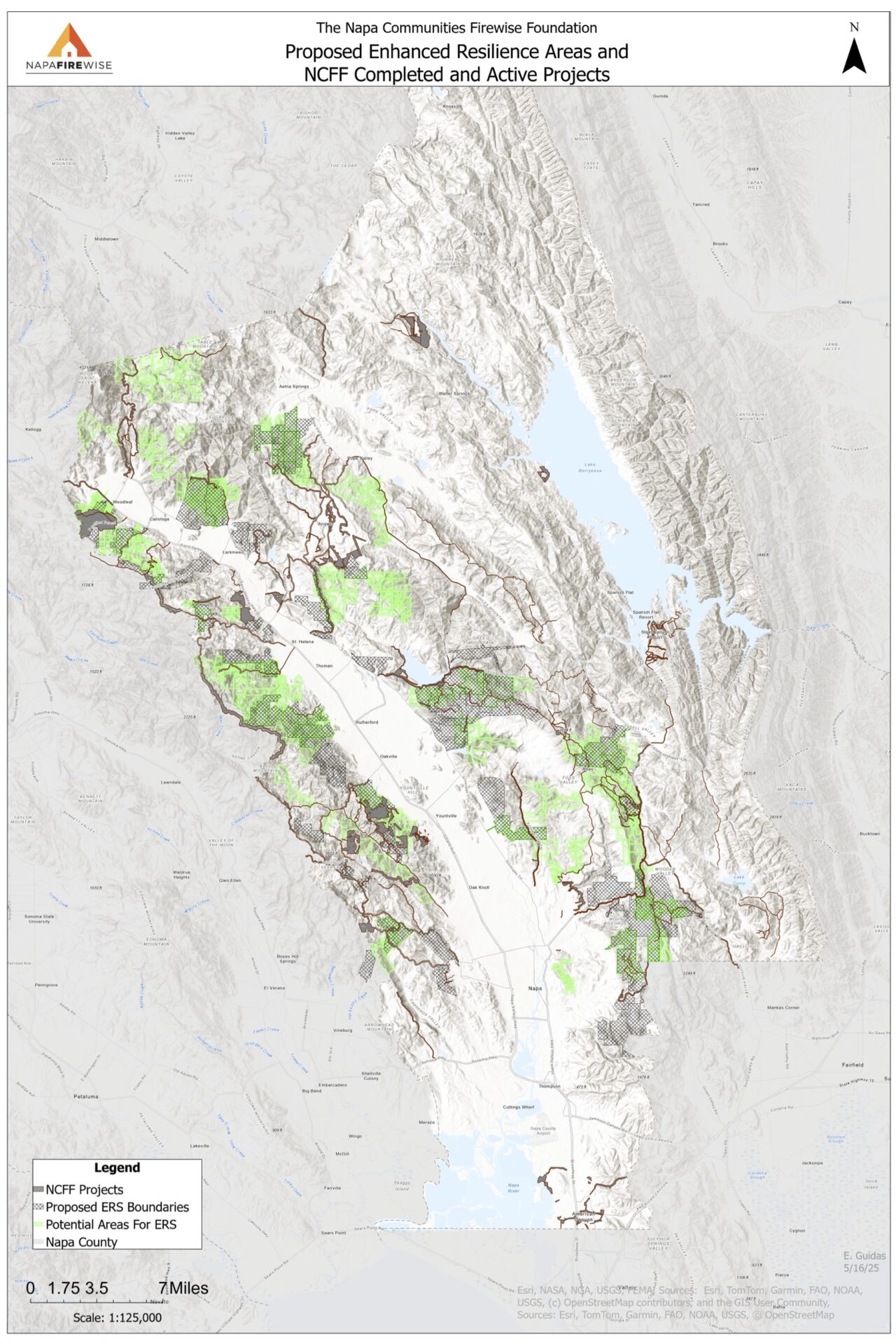

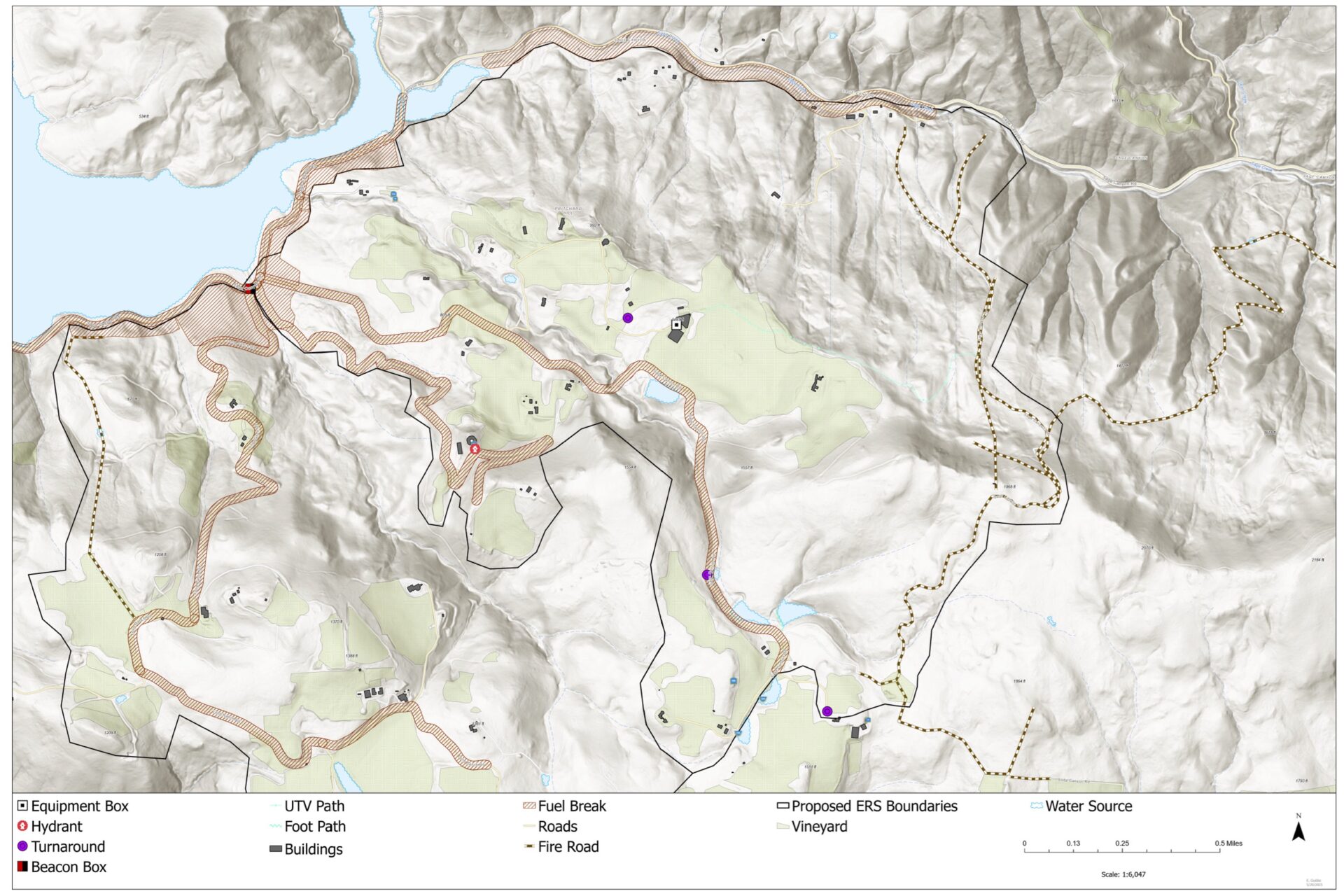

But getting this kind of result is not guaranteed. At least 50,000 acres of privately held forest land, both burned and unburned, needs treatment and management in Napa County, according to Firewise. If they can’t do that, they can at least develop what Nordlinger calls “enhanced resilience sites,” which he defines as an area of wild land, forested land, that is topographically strategic for wildfire containment.

“Generally, you stop fires on ridge tops, spur ridges and wide-open saddles and benches,” he says. “So throughout the county there are certain properties that have these characteristics important for firefighting.”

Recently, Firewise has been working closely with CAL FIRE, insurance companies, and large landowners to define and identify the county’s most likely enhanced resilience sites — with a target of sites of about 50-300 acres. They’ve started mapping all the places that have well-maintained roads, staging areas, water, and managed trees and vegetation. And now they’re integrating this information into an online system all firefighters use called “Tablet Command.”

“Those resilience assets are important, because when there’s a fire, the firefighting agencies need to know where that stuff is,” says Nordlinger. Firewise’s objective is to build 100 of these enhanced resilience sites over the next 10 years. To date, they have 139 parcels and 70 landowners signed up. These will be the best places to take a strong stand, he thinks.

“We hope to build 200 of these things in the next five years, which ultimately translates into something of value for insurance companies, and starts to move the needle on everything from more rapid containment to better insurance outcomes,” he says (see also KneeDeep’s Insurance Innovations story).

Since not everyone can afford enhanced resilience, Firewise is also gathering donations from large landowners to support smaller neighbors with fewer assets to do the right thing. And RCD, meanwhile, is encouraging all landowners to think about the woods. “A good place to start is to make a forest management plan, or even a mini-forest management plan if you have a really small property,” says Blodorn.

“Most landowners have to think really carefully about where they put their investments, which is where strategic planning and implementation comes into play. We can help them prioritize areas where there’s the highest fuel loads, or where we expect fire to travel and cause greater risk to life and structures.”

Another recent frontlines-fire-resilience tool is the Napa RCD’s prescribed burn association. The association is a mutual aid society of trained volunteers that helps landowners conduct safe, beneficial burns.

Photo: Afsoon Razavi

Five Fires Later

One of the first phone calls Rasmussen answered when the Pickett Fire flared up in August was from the local open space and parks district. He maintains an access road through Palisades Canyon that helps them clear trails in Robert Lewis Stevenson State Park, so they wanted to return the favor. They offered volunteers to help him stave off the Pickett Fire, which was licking at a far edge of his canyon. But this time CAL FIRE had the situation under control.

“CAL FIRE is getting better and better, and the county is getting better and better, and we’ve all learned a lot from these fires,” says Rasmussen. “I find that being as open as possible with everyone involved, and trying to do as much for them as you can, it just pays off big time.”

MORE

Note: the reporter is a landowner acquaintance of Steve Rasmussen.

EXTREMES-IN-3D

SERIES CREDITS

Managing Editor: Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Web Story Design: Vanessa Lee & Tony Hale

Art Director: Afsoon Razavi

Science Advisors: Alexander Gershunov, Patrick Barnard, Richelle Tanner, Emily Corwin, Terry Young

Series supported by the CO2 Foundation.

Top Photo: Afsoon Razavi