New Study Teases Out Seawall Impacts

Experts predict the San Francisco Bay Area will bear two-thirds of the damage from coastal flooding in the state this century, putting 400,000 residents and $150 billion in property at risk.

A new study suggests much of that damage will be the result of sea level rise, and can be avoided with a combination of shoreline protection strategies. An important consideration of these strategies, however, is their impact on Bay water levels.

The study, published in September in the Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal, and Ocean Engineering, examined the effectiveness of three kinds of flood mitigation strategies, as well as their potential impact on both water levels and tidal amplitude — the intensity of and range between high and low tides — in the Bay. Researchers at a Dutch technological institute, an Alameda County engineering firm, UC Santa Cruz, and UC Berkeley collaborated on the report.

This group of scientists determined that the most practical defense against flooding involves a mixture of both hard and soft strategies for Bay shorelines. They found that hard structures, such as seawalls and levees, will protect low-lying areas but minimally raise surrounding water levels, and that the restoration of wetland habitat, a soft shore, conversely would absorb water like a sponge. More importantly, modeling showed neither would affect water levels in the Bay significantly, though a more detailed look revealed some interesting twists useful to shoreline designers.

The more researchers and urban planners understand about the pros and cons of various flood protection strategies, “the more effectively we can move forward and plan and spend the limited resources we have on adapting to climate change,” says study author Patrick Barnard, research director at UC Santa Cruz’s Center for Coastal Climate Resilience.

Modeling Flood Scenarios

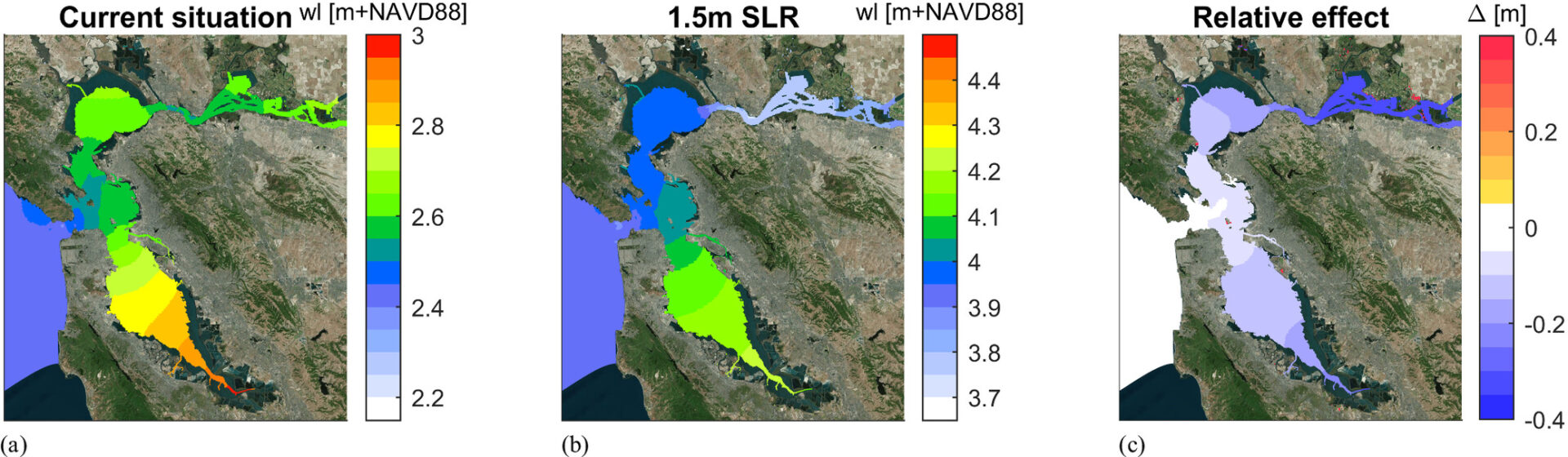

Barnard and his colleagues used a computer model they designed for an earlier study that simulates water level change as a result of different adaptation strategies in the San Francisco Bay Estuary. Their results cover tidal amplification, three resilience strategies, and a new understanding of the importance of hard structures’ locations.

Shoreline hardening, Barnard says, is the most realistic way to protect low-lying, populous areas or critical infrastructure, such as hospitals and schools.

But hard structures also funnel water to their flanks. “Unless you have a wall everywhere up to the sky, it’s going to very likely increase water levels in places where there aren’t walls,” Barnard says.

The study reports that shoreline hardening on its own could increase water levels by up to four inches (10 centimeters) for every five feet (1.5 meters) of sea level rise, an amount that’s unlikely to cause increased damage.

Other Recent Posts

Reforming Rules to Speed Adaptation

Bay Conservation and Development Commission to vote early this year on amendments designed to expedite approval of climate projects.

Warner Chabot Shifts Gears

After 11 years at the helm of the Bay Area’s leading science institute, its leader moves back into the zone of policy influence.

Is Brooklyn Basin Emblematic of Regional Development Vision?

The 64-acre waterfront development adds thousands of new housing units to one of the world’s most expensive places, but questions remain about its future.

Coordinate or Fall Short: The New Normal

Public officials and nonprofits say teaming up and pooling resources are vital strategies for success in a climate-changed world.

Pleasant Hill Gets Sustainable Street Improvements

An intersection redesign with safer bike lanes earned a national Complete Streets award, while sparking mixed reactions from drivers.

Six Months on the Community Reporting Beat

The magazine worked with four journalists in training from community colleges, and began building a stronger network in under covered communities.

Rio Vista Residents Talk Health and Air Quality

A Sustainable Solano community meeting dug into how gas wells, traffic, and other pollution sources affect local air and public health.

Extreme 10-year water levels across the Bay: (a) baseline; (b) 1.5 m SLR; and (c) difference. (Base maps from ArcGIS World Imagery, Sources: Esri, Maxar, Earthstar Geographics, and the GIS User Community.)

Ellen Plane, a coastal scientist at the San Francisco Estuary Institute who was not involved in the study, says the results provide a reality check for researchers and urban planners previously concerned that while a wall might protect one property, it might also just shift flood threats to neighbors.

“Yes, shoreline hardening will have some impacts, but it’s on the order of centimeters compared to meters of sea level rise,” she says. Plane’s work, including an SFEI report from earlier this year that she co-authored, focuses on Bay Area adaptation to coastal flooding.

Another finding from the modeling is that location matters. A levee constructed several kilometers farther inland, at the edge of urbanization, would raise tidal amplification significantly less — by less than one inch (two centimeters) for five feet (1.5 meters) of sea level rise. Moreover, coupling this strategy with the restoration of natural, soft shorelines counteracts the rising water levels.

The study also modeled scenarios centering two other adaptation strategies — large-scale wetland restoration (not accompanied by hardening) and floodgates. Both alternatives could lower or have a negligible effect on water levels, the models determined, but they’re likely not able to protect communities on their own.

“These findings point toward the justification for a range of adaptive measures across political boundaries, weighing hard and soft options in addressing the mounting danger of sea level rise,” the study abstract concludes.

More to Consider

These approaches to flood management do not represent the entirety of coastal resilience strategies. Other options include artificial reefs, “living seawalls,” managed retreat, raised dwellings, and more.

While seawalls slightly raise water levels, wetland restoration (such as at this site on the Marin County shore at Bahia) can lower them. Photo: Ellen Plane

Although the study closely analyzed how these three potential solutions could tackle sea level rise, it doesn’t examine the economic, social, or ecological implications of each option. Plane notes that seawalls and levees require a commitment to maintenance and to managing floodwaters behind them during storms or inland flooding events. Moreover, they can drown seaward ecosystems, Barnard says.

The bigger question is, “What kind of environment do we want to have in the future?” Plane asks. “I think this paper and the work that we’re [SFEI] doing points to the need for balanced solutions that account for those other benefits while trying to provide flood protection for areas that need it.”