Martinez Residents Want More Than Apologies — They Want Protection

Nearly three years after a massive release of toxic dust coated homes, gardens, and cars across Martinez, many residents say the question is no longer what went wrong at the oil refinery in their backyard in 2022 — but what it will take to make the community more resilient the next time something happens.

And lately, the “next time” feels less hypothetical, says Heidi Taylor, co-founder of the advocacy group Healthy Martinez and a local family law attorney.

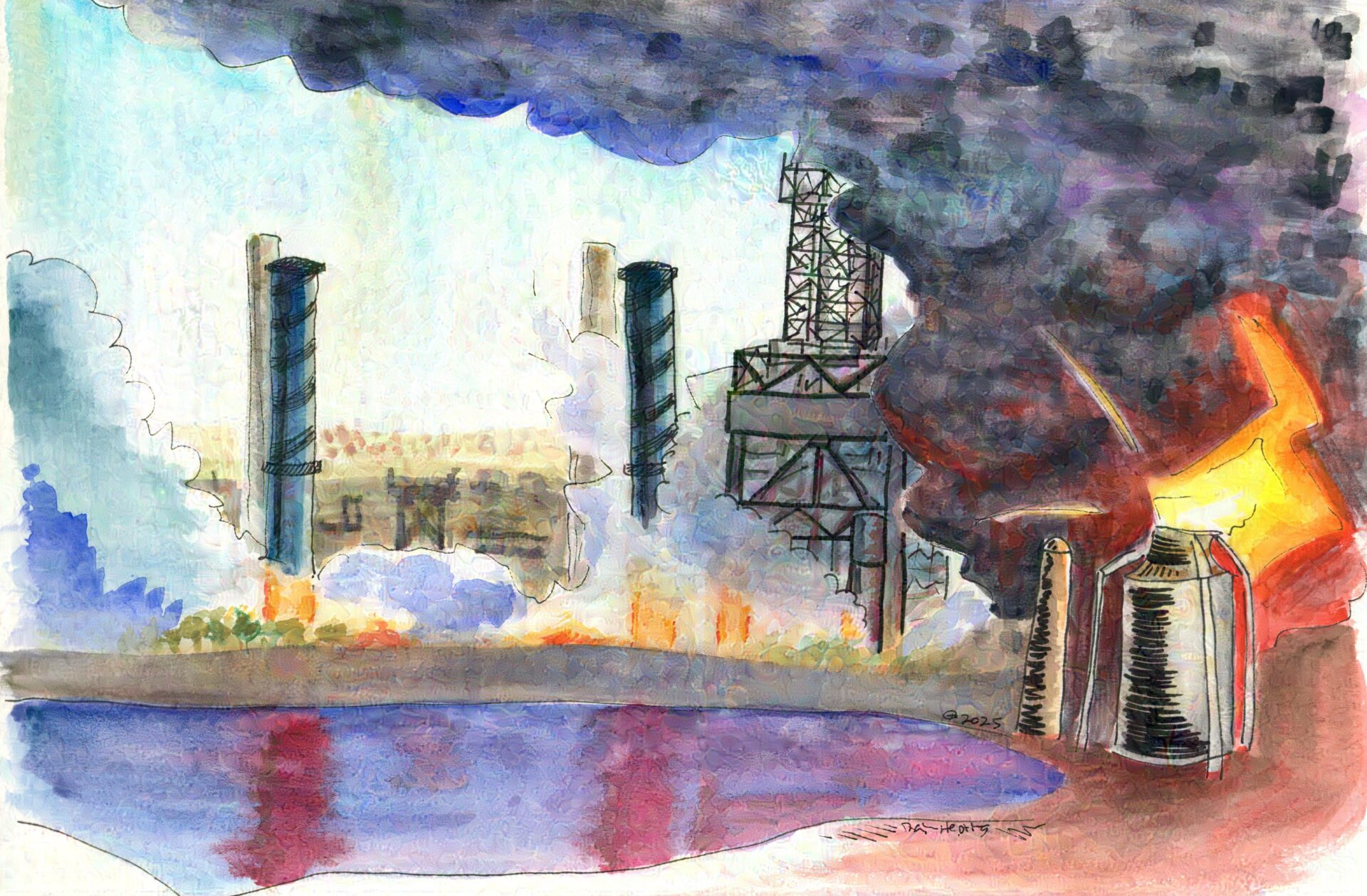

During a maintenance procedure at the Martinez Refining Company in February of this year, workers loosened bolts on a pressurized pipe, causing flammable hydrocarbons to escape and ignite. The fire spread in less than a minute, according to KQED, and sirens echoed across the city as residents scrambled to sort through text alerts, automated phone calls, and social media posts that at times offered conflicting instructions.

“Living in Martinez means you start the day with a smile and hope you end it with one,” says Taylor. “At any moment, you could get a Level 1, 2, or 3 alert, and it can derail your whole day. That’s just the reality here.”

For Taylor, who moved to downtown Martinez in 2022 — just months before the refinery’s release of toxic catalyst dust — the incidents reveal deeper, long-standing vulnerabilities in the town’s regulatory systems: older homes that offer little protection from outdoor air, an alert network that relies on a confusing mix of sirens and phone notifications, gaps in publicly accessible emissions data, and oversight processes that often leave residents learning about incidents long after they’ve happened.

“During the fire, we were sitting at our dining table with the sirens going off, asking whether we should go or stay,” she recalls. “Shelter in place only works if your home can actually keep toxins out. Ours can’t — and most homes here can’t.”

Martinez is a small town of roughly 38,000 people on the northeastern shore of the San Francisco Bay. Historically a hub of heavy industry, it sits along a corridor lined with refineries and chemical plants, with neighborhoods just blocks from industrial sites.

Healthy Martinez has distributed more than 1,000 HEPA filters to residents, but Taylor says individual stopgaps only go so far. “We’ve been kept in the dark and under-resourced,” she says. “We need accurate alerts, real air monitors, the best technology at the refinery, and real enforcement — not after the fact, but before something goes wrong.”

Contra Costa County has pledged to expand alert enrollment and improve messaging, but Taylor argues that what Martinez lacks is a resilient system built for frontline communities living in the shadow of fossil-fuel infrastructure.

The solutions she and other advocates outline resemble the broader climate-adaptation strategies emerging across the state:

- Real-time air monitoring that residents can trust

- Rapid, automatic exceedance notifications that don’t wait for regulatory agency approvals

- Upgraded home infrastructure — from windows to doors — for safe indoor air

- Clean-air centers modeled after responses to wildfire outbreaks

- A long-term transition plan for workers, contaminated land, and the refinery’s eventual closure

Other Recent Posts

Noticias en español

Encuentra más historias en español esta primavera, dentro de nuestro boletín KneeDeep con vecinos, y aquí en nuestro sitio.

Building Sustainably with Mass Timber

This building method can help clear forests of smaller trees that burn easily while also reducing the carbon footprint of new homes and offices.

Hardscapes That Filter Rain

Heavy rain can overwhelm storm drains and pollute waterways, but materials like permeable pavements help filter runoff and prevent flooding.

The Gray-Green Alchemy of Baycrete

Baycrete is a nature-based hybrid of concrete, shell, and sand designed to attract oysters and create shallow water reefs in SF Bay.

Tools Tweak Beaver Dams

Humans find ways to co-exist with beavers, tweaking dams to prevent flooding and create more climate resilience.

Hopes and Fears for Sierra Snowpack

February’s drought and deluge confirms that uncertainty may be a given for California snowpack, western water supply, and wildfire risk.

Errands by E-Bike

Electric cargo bikes are climate-friendly car replacements for everyday activities, from taking the kids to school to grocery shopping.

“If the only protection they offer is to shelter in place, then make sure our homes are safe places to shelter,” Taylor says. “Replace doors and windows. Provide safe food if our gardens get contaminated again.”

She argues that these upgrades shouldn’t fall on the homeowners, but that they should be funded by the refinery responsible for the hazards, also noting that it’s not standard for residents in any community to have to retrofit their houses because of industrial accidents. “Asking residents to fix their own homes because of refinery pollution is backwards,” she says. “The people creating the risk should be investing in our safety.”

The February fire forced the refinery to shut down major units for months. While MRC partially restarted operations in late April, it has been running at reduced capacity ever since. The company is now seeking approval to resume full production later this year.

California depends on the Martinez refinery for nearly 10% of the state’s fuel supply, and industry advocates point to its economic importance during the transition to renewable energy. But residents say the company’s poor safety record and growing health problems among locals are leaving frontline communities too vulnerable for their own good.

With MRC now preparing to resume full operations for the first time since the February fire, Taylor says the community is watching closely. “They’re getting ready to start up again, and the question is whether the safety culture is going to change,” she says. “I’m tired of waiting for them to do the right thing.”

Artist Rain Hepting is also a 2025-2026 Community Reporting Fellow with KneeDeep.

MORE

- The Path to a Just Transition for Benicia’s Refinery Workers, KneeDeep Sept 2025

-

Cleaner Air, Fewer Health Hazards from Bay Area Refineries, KneeDeep Sept 2021