“This means youth can be outside without constantly checking the air quality.”

In July, the Board of Directors of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District voted 19-3 to amend its Regulation 6, Rule 5, requiring fossil fuel refineries under its jurisdiction to reduce particulate matter emissions from their fluidized catalytic cracking units (“cat crackers” in refinery parlance), a major point source of pollution. The move gave the Bay Area the nation’s most health-protective and stringent regulation on particulate emissions, a recognized health hazard. Local environmental and environmental justice groups applaud the decision. “People see this as a huge victory,” says Steve Nadel of Sunflower Alliance. “Getting the strictest standard in place has a national impact.” Katherine Ramos, coordinator for the multi-group Richmond Our Power Coalition, describes the relief among the city’s youth: “This means they can be outside without constantly checking the air quality. We’re on our way to something better.”

The two corporations whose refineries will be affected, Chevron in Richmond and PBF Energy (a former Shell facility) in Martinez, responded by challenging the need for the new regulation, the science behind it, and the District’s estimate of compliance costs, with ominous references to potential refinery closures, higher costs to consumers, even excessive water use in a time of extreme drought. But the world is changing around them. Another local refinery, Valero in Benicia, has already installed equipment to cut catalytic cracker emissions, and two others are retrofitting to process renewable fuels. In Richmond, the idea of decommissioning the Chevron refinery is being taken seriously.

THE POLITICS OF CLEAN AIR

In many ways, Richmond has been the pivot point of a long struggle to contain refinery emissions. There’s literally no breathing room between Chevron’s facility and the city’s homes, schools, churches, and businesses. As Steve Early recounts in Refinery Town: Big Oil, Big Money, and the Remaking of an American City (2017), the Chevron corporation’s clout has shaped local politics for decades, while explosions and fires at the refinery, including a Level 3 event in August 2012, have rattled Richmond residents, who face disproportionate economic and health challenges even without the refinery’s impact.

Some Richmond activists were galvanized by the 2012 catastrophe. Others became involved with groups like Communities for a Better Environment and Sunflower Alliance in opposition to a plan to transport Alberta tar sands oil and Bakken crude from North Dakota over the Sierra Nevada and through the Sacramento Valley to North Bay refineries. Recognizing Richmond’s cultural diversity, the Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN) developed a ten-language warning system for Chevron refinery accidents. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, activists mobilized support for the change to Rule 6-5 through virtual town halls and workshops.

Art: Sophia Zaleski

The Air District’s Board of Directors, made up of elected city and county officials, adopted Rule 6-5 in 2015 to reduce particulate matter (PM). The rule needed to be strengthened to help the Bay Area meet state and federal standards and to comply with state legislation mandating technological retrofits at refineries covered by California’s cap and Trade program, along with efforts to reduce air pollution impacts on disadvantaged communities.

Air District staff originally presented two options for the amendments, one with a more stringent standard for PM. Community support helped advance the stronger alternative, which was endorsed by the District Board’s Stationary Sources committee, chaired by Emeryville Mayor John Bauters, in June. The amendments require the two refineries to cut PM2.5 emissions from a 2018 baseline of 800 tons per year to 529 tons per year by July 2026, with an estimated initial cost of $241 million for Chevron and $255 million for PBF. (Regulators refer to two size categories, PM10 and PM2.5, based on the width of particles in microns.)

CRACKERS, SCRUBBERS, AND ESPs

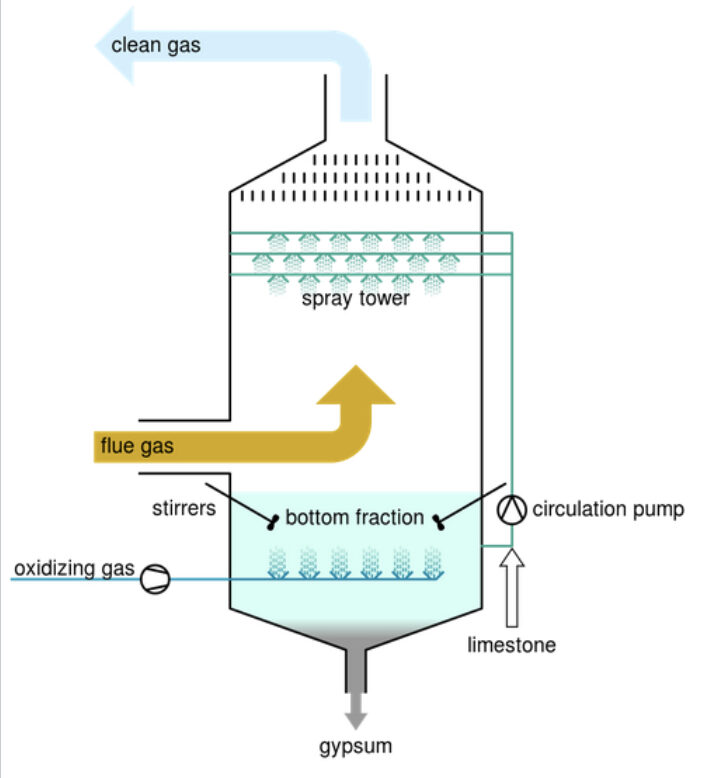

Contra Costa County Supervisor John Gioia, a District Board member since 2006 and former chair, grew up in Richmond and still lives there. His experience, including picking up his son at school during a shelter-in-place warning, has made him a committed advocate of emissions control. “I know how parents and families feel when you’re faced with something like that,” he says. “For many people it’s a traumatic event.” Between blowups, there’s steady exposure to PM. Gioia breaks pollutants down into three categories: “Greenhouse gases have global impact. Criteria pollutants [with national standards set by the US Environmental Protection Agency] like ozone, nitrous oxide, and sulfur dioxide have a regional impact in the Bay Area. And toxics like PM impact those directly breathing these particles. Over half of the PM from refineries comes from catalytic cracking units.” He says Air District staff provided a thorough analysis of who is impacted by the plumes from refineries, predominantly communities of color. “The Board’s decision was about making a commitment that we wanted to achieve equity,” Gioia sums up. Catalytic cracking units convert heavy components of crude oil into lighter products like gasoline and jet fuel. Burning off carbon that coats a unit releases PM and other pollutants. Two competing technologies, wet gas scrubbers and electrostatic precipitators (ESPs), can reduce catalytic cracker emissions. Wet gas scrubbers are regarded as not only more effective but safer. ESPs, currently used by Chevron and BFP, have a problematic track record. “An electric arc can spark an explosion, usually during startup or shutdown or when for any reason flammable gases get into the chamber,” explains former CBE staff scientist Greg Karras. In 2015 that happened at an Exxon Mobil refinery in Torrance, CA; no lives were lost, but the economic damage was calculated at $6.9 billion. While the ESPs used by Chevron in Richmond and PBF in Martinez haven’t blown yet, it’s a concern. Meanwhile, the wet gas scrubber option has been adopted by refineries all over the country—even in Texas—including four of PBF’s other refineries. Valero took that step in 2002 under a US EPA consent decree, although its scrubber was not operational until 2011. As the name suggests, wet gas scrubbers are water-intensive, a talking point for opponents of the regulatory change. But according to a CBE analysis, water use from a scrubber would represent only 2-4% of existing water use at the two refineries, an increase that could be compensated for by using more recycled water.BORN INTO ASTHMA

Many studies document the health effects of PM exposure: asthma and other respiratory illnesses, cardiovascular problems, and more. The smaller the particles, the more insidious: “There’s no safe level of exposure to PM 2.5,” says pediatrician Amanda Millstein, co-founder of Climate Health Now. Air District staff has calculated that PM from the refineries increases mortality by an annual average of 11.6 deaths for Chevron and 6.3 deaths for PBF. Researchers from UC San Francisco (UCSF) found that the incidence of asthma in Richmond, in the plume of the Chevron refinery, is twice the statewide average, 25% versus 13% and that Black and Latino communities in the Bay Area as a whole have much higher rates than other groups. “Children are born into it,” adds Ramos. Millstein recalls her early experiences with Richmond patients: “One of the biggest shocks of coming into practice in Richmond was the extent to which childhood asthma is ingrained in the community, that families have an expectation that their children will have asthma.” She remembers seeing newborn infants whose parents asked if their babies had asthma: “It caught me off guard—where is that coming from? Now I’m more aware of what goes on in terms of exposure.” She continues to see asthma in very young children, starting at a few months of age.

It’s not just the young who bear the brunt of PM exposure. Some evidence suggests that it can increase the risk for Alzheimer’s disease and other kinds of dementia. There’s also an emerging body of research linking PM to COVID-19 deaths and case rates. A Harvard team reported a positive association between historic PM2.5 exposure and county-level COVID death rates, even controlling for factors like age, race, and income. Another group found that last year’s Washington, Oregon, and California wildfires amplified the effect of even short-term PM2.5 exposure on COVID cases and deaths. No hard numbers on COVID in Richmond are available, but the toll there seems to have been disproportionate. Ramos knows families in North Richmond who lost two, three, or four elders: “An entire generation is gone.” The data may emerge soon: a UCSF project, funded by the California Air Resources Board, is examining the PM/COVID relationship on a census-tract level.

While the regulatory process grinds on, the Air District is moving to protect Bay Area residents from the effects of pollution sources at refineries and smoke from wildfires. In August the District expanded its Clear Air Filtration Program, which will provide portable air filtration units to low-income residents of impacted communities, shelters for the unhoused, and emergency and cooling centers. The District is also working on setting up clean air shelters in Bay Area communities.

THE CORPORATIONS PUSH BACK

In the runup to the Board’s vote, Chevron and PBF contended that the cost of compliance with the stronger alternative would be much higher than estimated by Air District staff, without explaining how they arrived at their own figures. Corporate responses after the decision included PBF’s initial threat to shut down its facility. In a later statement, PBF regional president Paul Davis, noting that the decision didn’t require the company to install wet gas scrubbers, gestured toward compliance: “PBF has previously planned projects that will be implemented over the coming months that will allow our Martinez refinery to achieve emissions reductions significantly closer to the desired level in the first quarter of 2022.” The first part is inarguable: the rule sets a goal but doesn’t specify the technology to meet it. “Currently the most promising technology is the wet gas scrubber,” Gioia explains. “If [the refineries] can demonstrate a technology that achieves that standard and it’s effective, that’s compliant with the rule. Currently our staff believes only the wet gas scrubber can meet the standard.”

Statements from Chevron’s Sean Comey and Brian Hubinger questioned the scientific basis for the rule change, warned of increased costs to consumers, and implied that the decision would be litigated. (Comey said the company was “investigating our options, legal and otherwise.”) If the companies sue, Gioia is confident that the Air District’s decision will stick. “Almost every rule the District has adopted has been challenged,” he says. “The refineries have frequently sued the District but have never won a lawsuit.” Comey also credited a refinery upgrade with reducing PM emissions: “Our refinery modernization project recently reduced particulate matter by 25% refinery-wide which is a greater reduction than anticipated by the rule adopted by the Air Board.” He provided no details on how the reduction was achieved or from what baseline emissions were reduced, and has not responded to a request for clarification.

According to CBE’s Richmond director Andres Soto, any emission reduction at the Chevron refinery would have resulted from lower sulfur content in the crude oil it processes, a change that the community had demanded. “Disputing the science is very Trumpian,” Soto adds. Karras points out that one of the conditions for the improvement project stipulated by the Richmond Planning Commission would in fact have required Chevron to reduce PM emissions, but that this was appealed by Chevron and voided by the City Council. He says flare emissions actually increased as the refinery expanded.

General diagram of wet gas scrubber, which removes harmful materials from industrial exhaust. Courtesy University of Calgary Energy Education.

TOWARD A JUST TRANSITION

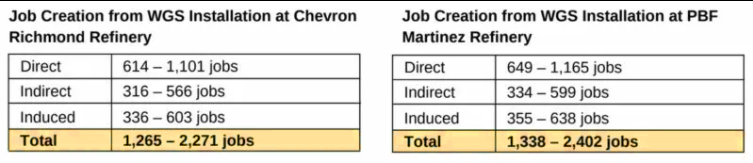

Along with the corporations and community activists, organized labor is the third point of the refinery triangle. Observers weren’t surprised that the Building Trades Union, representing contractors brought in for special refinery projects, denounced the Air District’s vote. “Building Trades and the Western States Petroleum Association have a formal alliance,” says Karras. Both Karras and Soto say the union has targeted Air District Board members who supported stronger regulations, sometimes successfully. Ironically, a study by UCLA’s Luskin Center found that installing scrubbers would create more than 4600 new jobs at the Chevron and PBF refineries.

Full-time refinery workers are represented by the United Steelworkers, which absorbed the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union in 2005. Their Chevron local has lately toed the corporate line, advocating for the weaker Rule 6-5 option. Fear of job loss if refineries shut down or downsize is a powerful motivator. But according to Karras, some rank and file members are standing up to union leadership on pollution issues. “We want to honor the refinery workers and listen to their voices,” Gioia insists. “The goal is not to shut a refinery down. But refineries will be closing as we transition from fossil fuels to electrification.”

That transition is already happening along the North Bay. “Refineries are seeing the writing on the wall, which is why Marathon and Phillips are investing in building renewable fuel facilities,” says Gioia. “Someone from one of the refineries that’s converting told me that they had evaluated many factors and saw the changes to Rule 6-5 coming down the track.” Marathon, which idled its Martinez refinery last year, and Phillips in Rodeo are switching to biofuels. (If Chevron and PBF have comparable plans for their Bay Area refineries, they’re not talking about them. Mark Nelson, a Chevron executive vice president, recently mentioned a biofuel project at the company’s El Segundo facility and an initiative to convert methane from dairy farms into natural gas.) Community activists like Soto, Nadel, Ramos, and Millstein stress the need for a just transition in which good jobs with benefits remain available, a goal that’s also gaining traction with union workers.

However serious Chevron is about life after fossil fuels, environmental justice groups in Richmond are looking ahead to life after Chevron. Following a 2020 report, “Decommissioning California’s Oil Refineries”, CBE, APEN, and others are holding weekly meetings to flesh out what a Chevron shutdown would mean for the city. Soto ticks off agenda items: “What are the policy choices and financial instruments we can use? How do we get refineries to pay now to ultimately clean up the sites after they’ve closed? How does Richmond replace the taxes that are coming from the refineries?” For these activists, decommissioning is clearly more than just a pipe dream.

Meanwhile, incremental regulatory steps are being taken. Climate health activist Amanda Millstein expresses a mixture of relief and frustration: “The rule change is a very good thing. It was long past overdue for the Air District to take action to protect the health of the communities that are most impacted. At the same time, it’s not enough and it’s not going to take effect soon enough. We know what we need to do is to get off fossil fuel as quickly as we can. If we want to avert catastrophic climate change we have to do it quickly and do it justly for everyone, including workers. We can’t leave people behind.”

More:

- News from Sunflower Alliance

- Climate Health Now

- Communities for a Better Environment Economics Fact Sheet

- CBE Cat Cracker Rule

- Air District Clean Air Filtration

- Air District Staff Report

- Harvard PM/COVID study

- COVID/wildfire study

- PM/dementia study

- PBF Energy statement

- Refinery Town

- Decommissioning report

- Breathing Room, Bay Area Monitor Story on Filtration Systems, September 2021