Mapping Those Most At Risk

When planning for climate disaster, many federal agencies assess risk on the scale of cities and counties. But in reality, neighborhoods within a city are impacted very differently from one another. A flood that hits Bayview-Hunters Point in San Francisco would pummel a dense, 96% minority community with a poverty rate nearly three times as high as the county average. That same flood in the Marina District would encounter a spread-out, predominantly white, and highly educated population with an average salary nearly ten times greater than Bayview-Hunters Point’s — making the area far more able to withstand the flood and bounce back.

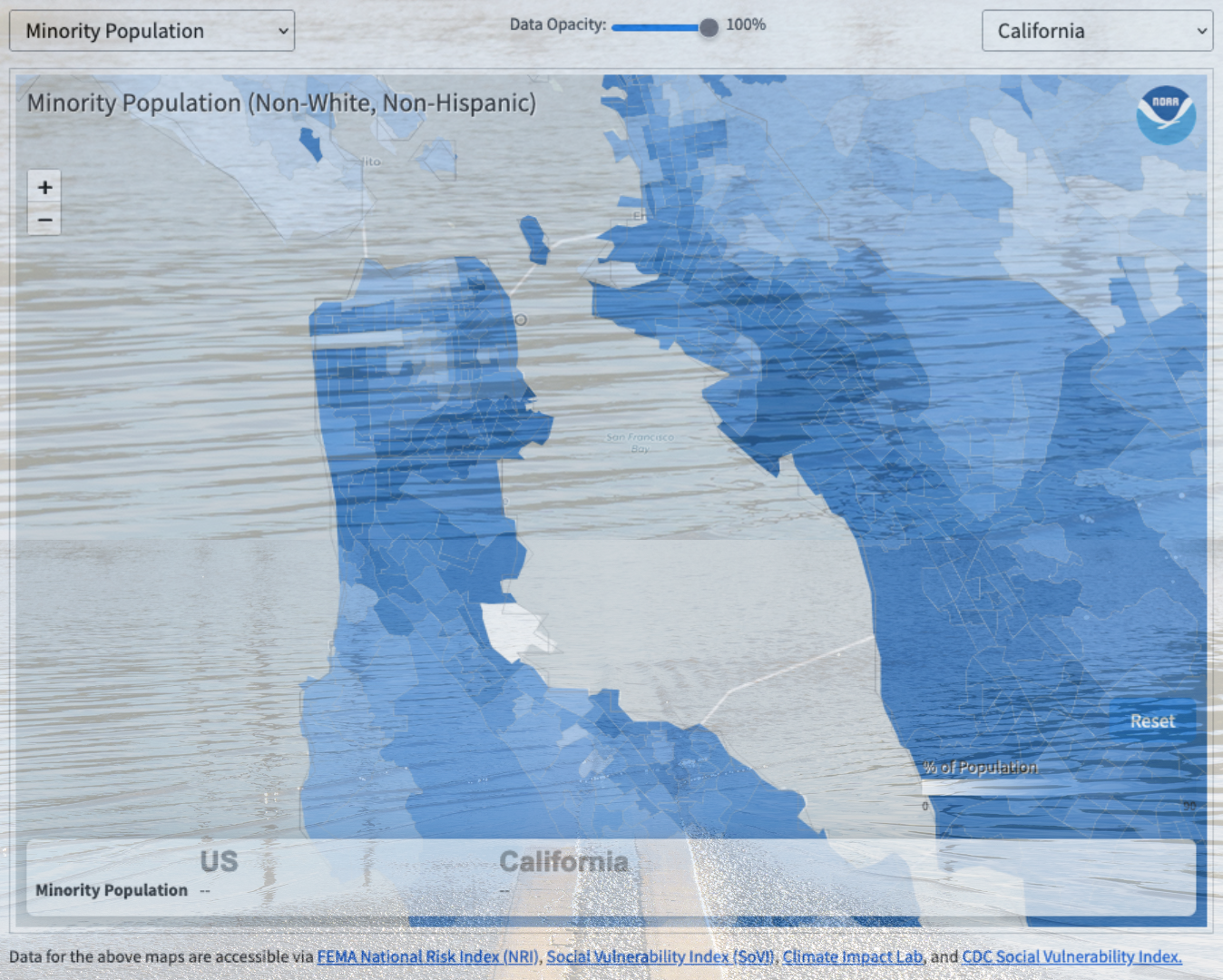

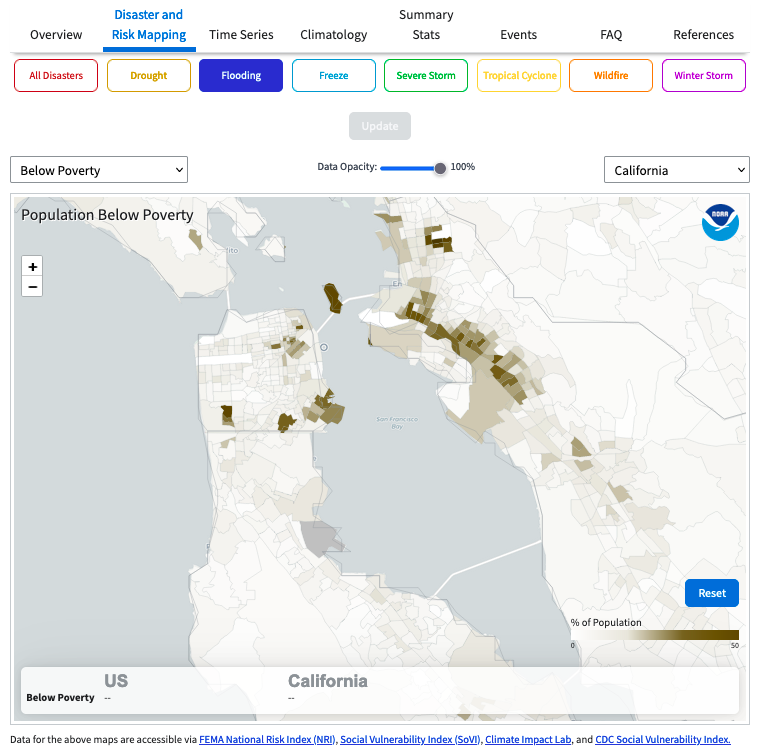

With the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s recent update to their long-running Billion Dollar Disaster Map, urban planners and citizens can see for themselves how disaster risk and vulnerability vary at the much finer “census tract” scale, representing about 4,000 people in a geographic area. Using the tool to look at “hazard risk” and “social vulnerability,” one can see how frontline communities like San Jose’s Alviso, Marin City, the San Rafael Canal District, East Oakland, and others stand out in stark contrast to the wealthier, whiter neighborhoods around them. The tool shows which census tracts have a significant number of people with characteristics that contribute to social vulnerability — for instance, those without vehicles, senior citizens, or the mobility-challenged. Or race, income, and educational level, which correlate with lower access to essential government programs and services that are essential to helping people and communities rebuild after a disaster.

As risk maps go — and there are an overwhelming number out there — NOAA’s is still a little clunky. The census tract view is hidden in a drop-down menu above and to the right of the map, and to look at historic flood hazard risk one has to manually de-select all six other hazard types. The Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s regional Community Vulnerability map is even more granular, analyzing vulnerability at the small “census block” scale (geographic areas of 3,000 people or less), and it also indicates contamination exposure. But hopefully NOAA’s update represents progress toward seeing pre-existing risk and vulnerability disparities within a city or county, and taking ameliorative steps before the next disaster exposes and widens them.

Other Recent Posts

Tools Tweak Beaver Dams

After witnessing fire disasters in neighboring counties, Marin formed a unique fire prevention authority and taxpayers funded it. Thirty projects and three years later, the county is clearer of undergrowth.

Reforming Rules to Speed Adaptation

Bay Conservation and Development Commission to vote early this year on amendments designed to expedite approval of climate projects.

Warner Chabot Shifts Gears

After 11 years at the helm of the Bay Area’s leading science institute, its leader moves back into the zone of policy influence.

Is Brooklyn Basin Emblematic of Regional Development Vision?

The 64-acre waterfront development adds thousands of new housing units to one of the world’s most expensive places, but questions remain about its future.

Coordinate or Fall Short: The New Normal

Public officials and nonprofits say teaming up and pooling resources are vital strategies for success in a climate-changed world.

Pleasant Hill Gets Sustainable Street Improvements

An intersection redesign with safer bike lanes earned a national Complete Streets award, while sparking mixed reactions from drivers.

Six Months on the Community Reporting Beat

The magazine worked with four journalists in training from community colleges, and began building a stronger network in under covered communities.

Rio Vista Residents Talk Health and Air Quality

A Sustainable Solano community meeting dug into how gas wells, traffic, and other pollution sources affect local air and public health.

New Year Immerses Concord Residents in Flood Preparations

In Concord, winter rains and flood risks are pushed residents to prepare with sandbags, shifted commutes, and creek monitoring.

What You Need to Know About Artificial Turf

As the World Cup comes to the Bay Area, artificial turf is facing renewed scrutiny. Is it safe for players and the environment?