Swale and drain in stormwater park. Photo: Ariel R Okamoto

The Race Against Runoff

Few of us give stormwater a second thought — at least until it backs up. That’s why watershed planner Sarah Minick, who has dedicated her career to the subject, is so excited that an innovative new park in San Francisco’s Mission Bay neighborhood has been named accordingly. “It actually says ‘Stormwater Park’ on Google Maps,” she gushes. Completed in 2022, the 1.2-acre park sits on the edge of a sprawling former parking lot near the Giants’ home stadium, and drains into Mission Creek. Previously, any rain that fell here would flow straight to the channel and then San Francisco Bay, carrying with it motor oil, gasoline, microplastics, and trash from the expanse of pavement. But with the recent redevelopment of the neighborhood, the city added this lush, green promenade, underneath which lies a network of drains, pipes, and channels that together help capture and clean stormwater. It’s just one of many new green stormwater infrastructure projects across the city and entire Bay Area where engineers and water managers are pushing the design envelope to handle dirty runoff rushing toward the Bay and ocean – but can they keep up with increasingly severe storms?

Extremes-in-3D

A seven-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Supported by the CO2 Foundation.

FULL READ

The Race Against Runoff

Few of us give stormwater a second thought — at least until it backs up. That’s why Sarah Minick, who has dedicated her career to the subject, is so excited that an innovative new park in San Francisco’s Mission Bay neighborhood has been named accordingly.

“It actually says ‘Stormwater Park’ on Google Maps,” gushes Minick, an urban watershed planning manager with the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. “That’s cultural progress.”

Completed in 2022, the 1.2-acre linear park sits on the edge of a sprawling former parking lot abutting Mission Creek. Directly across the waterway — also known as China Basin Channel — sits Oracle Park, the San Francisco Giants’ home stadium.

A view of tree-lined Mission Creek Stormwater Park and the newly redeveloped Mission Bay neighborhood, whose runoff it helps capture and clean. Photo: Ariel R. Okamoto

Previously, any rain that fell here would flow straight to the channel and then San Francisco Bay, carrying with it motor oil, gasoline, microplastics shed from tires, trash, and other environmental pollutants.

But with the recent redevelopment of the Mission Bay neighborhood, the city also added this lush promenade. Beyond being beautiful, it’s paved with permeable surfaces and densely planted with mostly native grasses, shrubs, and trees in soil concealing a network of drains, pipes, and channels that together help capture and clean stormwater from a 9.6-acre catchment area before releasing it to the creek.

Mission Creek Stormwater Park, which attracts thousands of visitors on game days, is first and foremost a public thoroughfare — streetlights and picnic tables included. But just as important is its ability to capture and treat three-quarters of an inch of rainfall over 24 hours, or approximately 694,000 gallons of stormwater annually.

EXTREMES-IN-3D

A seven-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Series Home

Click here to enter

Part 6: Infrastructure

Part 7: Aftermath

Supported by the CO2 Foundation.

Click through to view multiple slides above

That’s a lot of potentially dirty water not flowing straight to the Bay. But it’s just a drop in the bucket relative to San Francisco’s bigger goals with green stormwater infrastructure, a term that refers to natural, permeable surfaces engineered to capture and absorb rain and other runoff rather than letting it flow over hard urban streetscapes into a water body or sewer drain.

In a city with a combined sewer system that processes stormwater and sewage simultaneously, green stormwater infrastructure plays a particularly important role in helping protect water quality in both the Bay and the Pacific Ocean. That’s because, when the amount of rain falling on the city exceeds the system’s ability to handle it, overflows occur. Like activating an emergency relief valve, the city is forced to discharge minimally treated wastewater, a mix of runoff and sewage, instead of the fully cleaned and sanitized effluent it typically does.

The diversionary role of green stormwater infrastructure is all the more crucial in a time of climate change, when winter storms are likely to become more and more severe, albeit less frequent, holding more and more water and delivering it in briefer, more intense bursts.

Building Out the System

San Francisco received about 20 inches of rain last year, slightly below its long-term average of 23. More notable from a climate-change perspective, however, is that almost 13 of these inches, or nearly two-thirds of the total precipitation, arrived in just four major, multi-day rainstorms between November 2024 and February 2025.

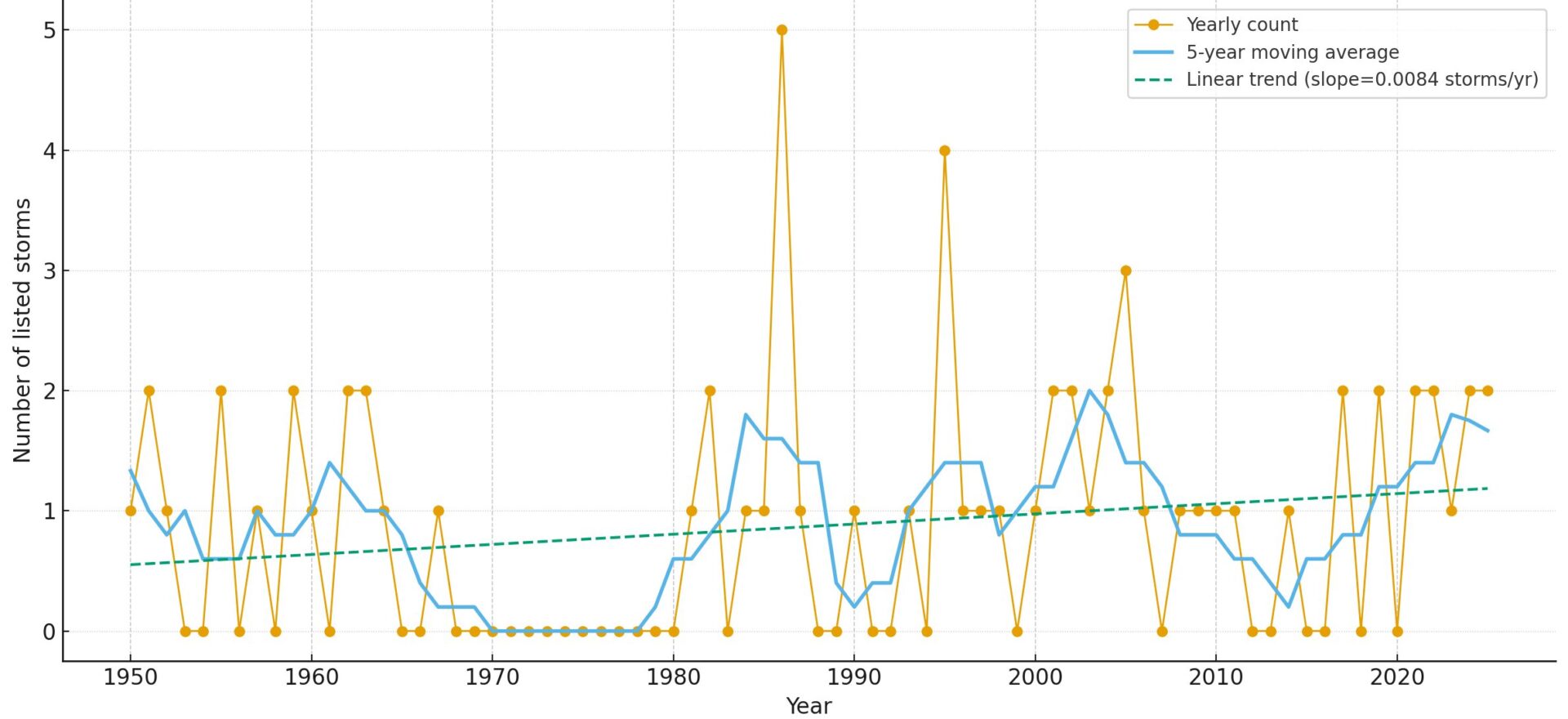

According to meteorologist Jan Null’s Bay Area Storm Index, very large storms have become slightly more common in the region since 1950, the first year for which data is available. Thirteen such extreme storms (also accounting for wind speeds) have occurred since 2017.

Trend in large storms listed in the Bay Area Storm Index, showing an increase in frequency since 2017. Source: BASI

But even more moderate events can overwhelm San Francisco’s combined sewer system. Last winter, six storms caused overflows, says SFPUC press secretary Nancy Crowley, releasing to the Bay and Pacific Ocean well over a billion gallons of wastewater treated only to remove solids.

Climate change’s promise of larger, wetter storms thus looks something like a double-edged sword for the city: on one side, perhaps, a reduction in the sort of mid-tier storms that may or may not lead to smaller overflows; and on the other, an increase in larger storms that existing infrastructure isn’t equipped to handle and that result in the greatest overflows by volume.

To take some of the pressure off its network of pipes and three treatment plants, and ensure that as much stormwater as possible is still treated before it reaches the shore, the city has a goal to manage one billion gallons of rainwater with green stormwater infrastructure by 2050 — about a tenth of the approximately 10 billion gallons that fall on the city every winter.

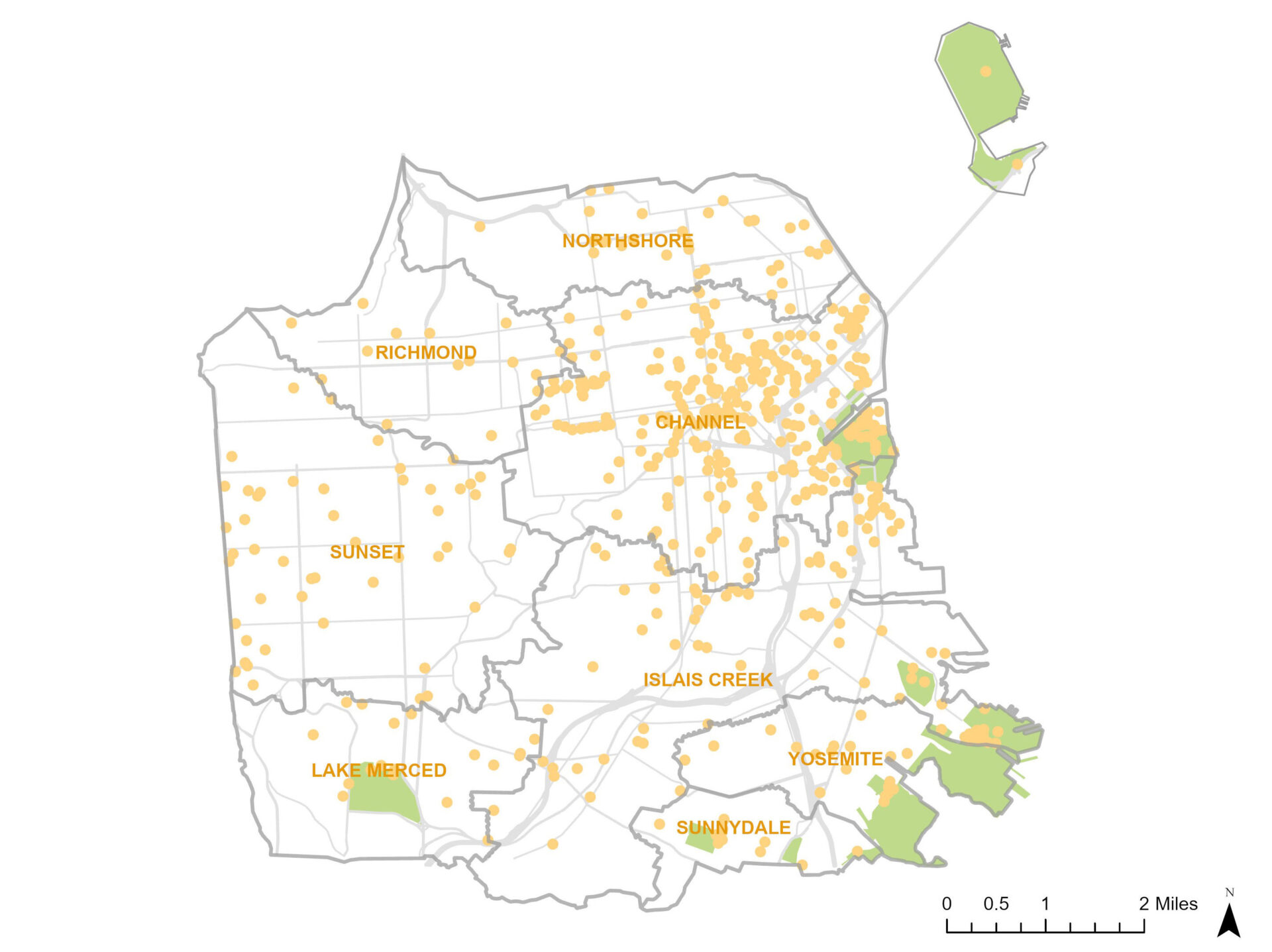

Mission Creek Stormwater Park’s 694,000 gallons is a tiny piece of that — 0.07%, to be precise — but on a citywide scale, San Francisco is almost a third of the way toward its goal with 25 years to go, Minick says. The current total is 293 million gallons captured by 530 permeable parks, rain gardens, and other projects, with new ones coming online regularly.

Click through to view multiple slides above

India Basin’s three-year-old Southeast Community Center is surrounded by green infrastructure landscaped with native grasses, shrubs, and oaks and centered on a rock-lined, man-made creek bed that meanders from the edges of the building across the grounds, crossed here and there by stepping-stone foot bridges. This semi-natural, pervious landscape collects, funnels, and filters stormwater through the soil that would otherwise enter a street drain.

Out on the city’s ocean coast, another newer project treats stormwater along a major thoroughfare. For 12 blocks and nearly two miles between Irving and Ulloa streets, Sunset Boulevard is lined with 30 rain gardens featuring drought-tolerant plants that help capture and rapidly sink rainwater through the Sunset District’s porous, sandy soils. Completed in 2021, the project is estimated to capture 5.3 million gallons of stormwater annually.

Sunset Boulevard’s 30 rain gardens employ careful grading and planting to capture and sink stormwater through the underlying sandy soils. Photo: Ariel R Okamoto

Set to begin construction in the spring is an even larger project that will manage stormwater from 106 acres of McLaren Park, including excess flows from Yosemite Marsh and McNab Lake — in all, more than 10 times the catchment area of Mission Creek Stormwater Park.

While all of these projects confer multiple benefits, including bringing valuable greenery and habitat to city streets and parks, their raison d’etre is singular: “Every drop that we take off in the green infrastructure is another bit of capacity that our sewer system has,“ Minick says.

San Francisco’s decades-long efforts to reduce sewer overflows — including other infrastructure improvements like adding more than 200 million gallons of underground storage — “have been tremendously effective,” Crowley says, “reducing the volume of the citywide combined-sewer discharges by over 80%.” Prior to 1976, overflows occurred during every rainstorm: up to 30 times a year or more. These days, the average is closer to 10 — but that’s still too much.

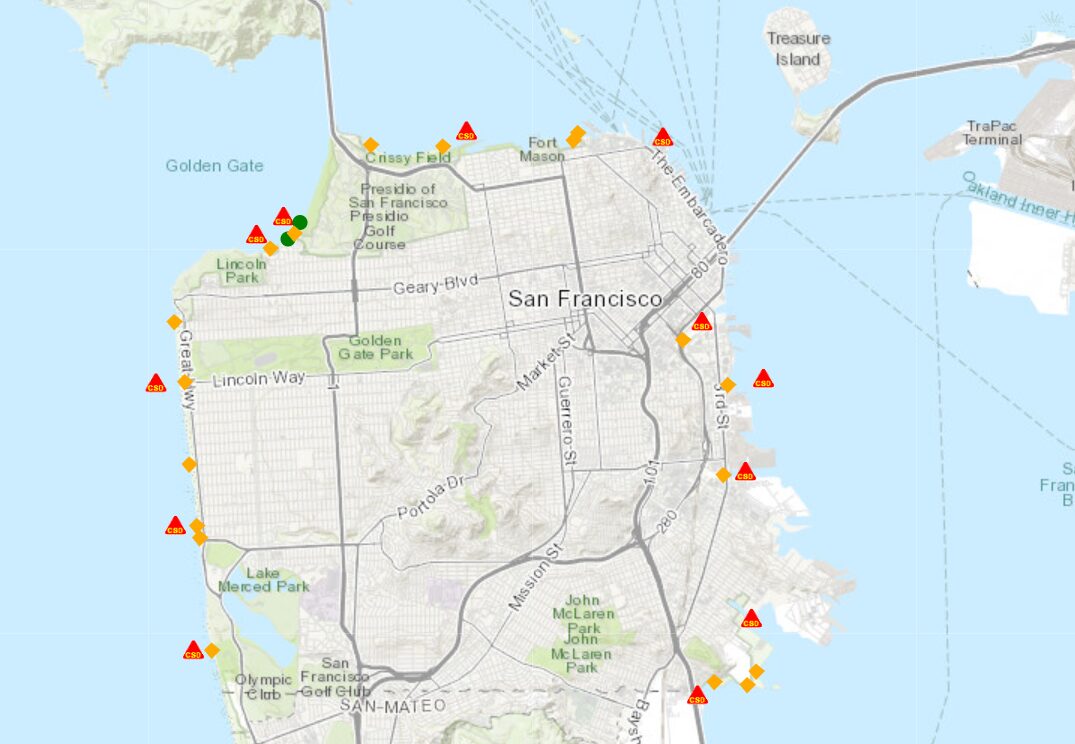

Sewage overflows from one storm during 2024-25 winter (red triangles are untreated discharge). Source: SFPUC

San Francisco has two primary wastewater treatment plants, one by the ocean and one by the Bay, as well as a wet-weather backup located two blocks from Pier 39. When all three plants and their networks of pipes are overwhelmed, the system discharges partially treated sewage through some of its 36 smaller combined-sewer outfall pipes dispersed along the city’s west, north, and east shores.

Given its position on the sensitive San Francisco Bay and responsibility for the vast majority of the city’s wastewater, the Southeast Treatment Plant is especially critical. And a big part of it, called the Headworks Facility — wastewater’s first stop of the plant — just underwent a major renovation to minimize odors and improve the removal of grit and debris.

While the new plant is indeed an impressive 95% more efficient, as well as able to withstand larger earthquakes and 36-plus inches of sea level rise, one thing it’s not is any larger or more capable of handling higher-volume peak flows of the sort threatened by climate change. “We did bring in the best minds, but there is nowhere to go in terms of a footprint,” Crowley says. “With the footprint that we have, we’ve made remarkable advanced improvements.”

As an alternative to upsizing, she reiterates, the city is continuing to lean on green stormwater infrastructure to help keep stormwater from arriving at the facility in the first place.

An aerial view of San Francisco’s new $717 million Headworks Facility, which treats about 80% of the city’s wastewater and stormwater through the combined sewer system. Photo: SFPUC

Missed Opportunities

The Headworks is not the only newer large-scale stormwater-management facility in the Bay Area to be designed without additional capacity for the increasingly powerful atmospheric rivers likely headed our way.

Farther down the Peninsula in the city of South San Francisco, the Orange Memorial Park Stormwater Capture Project, completed in 2022, collects, cleans, and even reuses stormwater flowing to Colma Creek from a catchment area of more than 6,500 acres across six different municipalities.

Designed to reduce discharges of PCBs, mercury, trash, and other contaminants from urban stormwater runoff to the Bay, Orange Memorial Park is the first regional stormwater project of its kind in the Bay Area and has won multiple awards. The project, which relies on a massive storage basin built beneath four baseball and softball fields, conserves approximately 15 million gallons of water per year, recharges 55 million gallons of groundwater, and returns 130 million gallons of clean water to the Bay.

Click through to view multiple slides above

What it’s not designed to do is mitigate flooding from severe winter storms, now or in the future, says Robert Dusenbury, a principal engineer with Lotus Water, the San Francisco-based firm that led the project.

“The project was funded and designed primarily as a water-quality and water-reuse project. While it does have some local flood reduction benefits, they are not of the magnitude to deal with the predicted future scale of flooding,” Dusenbury says. “We informed the city during design that the fields would have to be lowered five-plus feet to create overflow detention at the scale that would provide significant flood benefits. The Parks Department declined that option.”

In San José, another large stormwater facility recently underwent a major renovation without adding any new flood-control capacity. Upon its completion this past April, the new Riverview Stormwater Garden transformed a barren flood basin, first constructed in 1979 to temporarily store stormwater during heavy rainfall, into an exemplar of green infrastructure that diverts and treats low stormwater flows via soil filtration and plant uptake before discharging into the adjacent Guadalupe River, which runs straight to San Francisco Bay.

Jason Day, a senior engineer with the San José Public Works Department, says the city’s first regional green stormwater infrastructure project is principally a water-quality solution for lower-volume storms that adds little to existing flood protection. “We basically maintained our 100-year storm capacity for this particular system,” he says.

Though the city did excavate a bit more space out of the basin itself, slightly increasing the volume it can hold during big storms, the capacities of the pumps needed to send water back to the river, and of the river channel itself, remain unchanged.

“If we upsized our pumps at this location, we would, in theory, increase the capacity that the system has for the 344 acres that drain through this outfall and pump station,” Day says. “That’s a real limiting factor for the flood capacity in this catchment area of San José.”

Throwing the Works at the Problem

The reality of the situation in which the Bay Area and much of California now finds itself — not to mention many other regions around the world also anticipating heavier rainfall with climate change — is that we may never be able to out-run the problem.

“No sewer system can capture and manage the flows generated by every storm,” says Crowley of the SFPUC. “Building pipes, pump stations, and storage vaults large enough to prevent flooding during extreme storms is not cost-effective, is infeasible in many instances, and can sometimes be impossible.”

Instead, “[San Francisco] is taking a multi-pronged approach to addressing flood resiliency,” Crowley says. This includes, of course, all those hundreds of green stormwater infrastructure projects and various underground storage vaults, but also something a bit more surprising that may represent the shape of things to come in flood-prone areas and along the Bay shore: designing new buildings and other street-level infrastructure to withstand occasional flooding.

“The industry direction is more going into the idea of trying to build our cities to be more flood resilient,” Minick agrees. “One of the efforts that SFPUC is working on jointly with other city agencies is a proposal to include flood resilience in our building code, so that new buildings would be built flood resilient from the get-go, instead of suffering flood damage later if they haven’t taken that into account.”

Green infrastructure projects in San Francisco. Map: SFPUC

This way, Minick says, multiple measures are working together: “the combined sewer system, which manages a lot of stormwater, but it can’t do it all; green infrastructure, which layers on more performance, but it can’t do it all; and then urban design and architectural measures to keep cities safe from really high flood levels.

Keith Lichten, a supervising engineer with the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board, which regulates stormwater discharges into the Bay, says climate change is front of mind for the water board and the municipalities and agencies it oversees.

“We have required the permittees to submit a climate change adaptation report by September 30, 2026,” Lichten says. “It’s an opportunity for them to reflect on and put down in writing a lot of discussions that we’ve been having for the last five or 10 years about how we might want to modify things we’re doing as we recognize that storm patterns are changing. Things are going to get wetter and drier: more drought years and more flood years.”

For Gregory Pasternack, a professor of hydrology at the University of California, Davis, the situation calls for entirely new perspectives on flood control. A strictly linear approach to scaling up 100-year storms and employing decades-old models to predict their impacts on streets and waterways may be doomed to fail.

Instead, he argues, a qualitative analysis of recent storms may prove more fruitful at minimizing impacts as municipalities chart their paths forward.

“It’s not just that there’s more water, it’s that the nature of the storms have changed,” Pasternack says. “Within climate science, there’s a movement toward other ways of knowledge production about floods through climate storytelling and impact assessment. Instead of starting from, ‘Here’s a hundred-year storm, now let’s see what that creates,’ instead you say, ‘Well, let’s look at the floods we’ve actually had in the last five years, and let’s work backwards.’”

One lesson to emerge from the January 2023 flooding of East Palo Alto, for example, is that San Francisquito Creek became clogged with debris that caused it to spill its banks sooner than it should have, Pasternack says: “When you have debris and trash coming down at a different scale, you cross a threshold.”

Despite an unusual series of early-season atmospheric rivers in October and November, winter is off to a mild start in San Francisco. The city has received 3.5 inches of rain as of December 16 — about 65% of normal rates — after weeks of cold, dry weather.

But things can change quickly, especially in an increasingly unstable climate, and sooner or later Mission Creek Stormwater Park and the rest of San Francisco’s extensive, mostly hidden stormwater system will again be put to the test. Sarah Minick, Nancy Crowley, Keith Lichten, and many others will be watching closely, even if the rest of us — rightly, perhaps — simply expect it to work.

MORE

- Can Colgan Creek Do It All? KneeDeep 2025

- San Pablo Spine is Green Streets Test Lab, KneeDeep 2022

- Being Human in Big Weather, KneeDeep 2023

- Mega-Developments Hedge Against Sea Level Rise, Estuary News 2020

- GSI Municipal Regional Permit Planning, Estuary News 2019

- LA Drainage Goes Native, Estuary News 2017

EXTREMES-IN-3D

SERIES CREDITS

Managing Editor: Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Web Story Design: Vanessa Lee & Tony Hale

Art Director: Afsoon Razavi

Science advisors: Alexander Gershunov, Patrick Barnard, Richelle Tanner, Terry Young, Emily Corwin

Series supported by the CO2 Foundation.

Top banner photo: Courtesy City of San Jose