Forest tech sorts seeds. Photo: Janet Byron

Reforesting a Fiery, Warming World

While many bird species are responding to global warming by gradually shifting their ranges northward to cooler and higher elevations, trees don’t have that luxury. “We humans need to step in and assist,” says CAL FIRE Statewide Reforestation Coordinator Topher Byrd, one of the program directors of a tree seedbank and seedling nursery located in Davis. CAL FIRE has been collecting native tree seeds from California forests since the 1970s, and more than 23 tons are now stored in a large walk-in freezer at the nursery. For decades, reforestation managers chose seed to grow seedlings for replanting by matching the target forest area with the same or a similar seed zone. But relying solely on these zones, without considering climate change, risks introducing trees that are maladapted to the place where they’re replanted.

Extremes-in-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

FULL READ

Reforesting a Fiery, Warming World

While many bird species are responding to global warming by gradually shifting their ranges northward to cooler and higher elevations, trees don’t have that luxury.

“We humans need to step in and assist,” says Statewide Reforestation Coordinator Topher Byrd of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or CAL FIRE. Byrd is one of the program supervisors at CAL FIRE’s Lewis A. Moran Reforestation Center in Davis, a tree seedbank and seedling nursery.

CAL FIRE has been collecting native tree seeds from native California forests since the 1970s, and more than 23 tons are now stored in a large walk-in freezer at the Moran Center, including conifers such as Jeffrey pine, Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, coast redwood, giant sequoia, incense cedar, and a few native hardwoods like western redbud and Pacific madrone.

Seedlots in cold storage at the Moran Reforestation Center. Photo: Janet Byron

When the vast majority of those seeds were collected, their provenance was identified in 1 of 87 California tree seed zones. For decades, reforestation managers chose seed to grow seedlings for replanting by matching the target forest area with the same or a similar seed zone.

At higher elevations, however, growing conditions within the seed zones can vary significantly, with up to 500 feet of elevation change and large differences in temperature and precipitation. Seed zones are “pretty arbitrary boundaries,” says Derek Young, Ph.D., a research ecologist in the Department of Plant Sciences at the University of California, Davis. Relying solely on these zones, according to Young, risks introducing trees that are maladapted to the place where they’re replanted.

“Reforestation based on seed zones alone is being called into question because of an uncertain future climate,” CAL FIRE wrote in its 2017 Forests and Rangeland Assessment.

With climate change accelerating, reforestation managers and scientists now recognize that the boundaries of California’s tree seed zones are shifting — historically cooler, high elevation areas are getting warmer — and they must develop new replanting strategies that prioritize seeds adapted to warmer growing conditions.

A Monumental Task

Forests provide myriad ecosystem benefits: biodiversity, wildlife habitat, erosion control, reliable water supply, and, perhaps most importantly, carbon sequestration. When forested areas are not replanted after wildfires, brush species can quickly take over, and trees may never regenerate on their own.

“If the shrubs get in and dominate a site within the first five years, it will take decades for trees to recover, if they ever do,” Young says. “Even if another vegetation type grows in its place, it often doesn’t provide the same services or at the same level as forests do.”

California wildfires decimate an average of 975,000 acres every year — an area of about 1,500 square miles, or roughly the size of Rhode Island. CAL FIRE estimates that 1.8 million acres of private, nonindustrial forestland in the state need to be reforested.

“This is a monumental task, and every year that we experience wildfires, that target grows,” Byrd says.

Allison Veiga preps seedlings. Photo: CAL FIRE

EXTREMES-IN-3D

A seven-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Series Home

Click here to enter

Part 6: Infrastructure

Part 7: Aftermath

Supported by the CO2 Foundation.

At the same time, the U.S. Forest Service estimates that 4 million acres of the West’s national forests also need replanting due to wildfires, and it operates a seed bank and nursery in Placerville to grow seedlings for restoring vast tracts of public land. Large operations like Sierra Pacific Industries and Cal Forest Nurseries operate their own seedling nurseries for reforesting private lands after logging and, increasingly, wildfires.

When forests burn, they release huge amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, making the need for reforestation all the more urgent.

“My back-of-the-envelope math suggests that by starting now and letting trees grow for about 30 years, we can expect those replanted forests to sequester about 1% of California’s peak greenhouse gas emissions on an annual basis,” says Joseph Stewart, a UC Davis resource ecologist. “This is a strategy that can substantially contribute to addressing and hopefully reversing climate change.”

Growing Seeds & Seedlings

The Moran Center opened in 1921 to grow seedlings for planting along California highways and at schools. Its focus soon shifted to support reforestation, windbreaks, and erosion control, and seedling nurseries were added in Santa Cruz, Mendocino, and the Sierra Nevada foothills.

State budget cuts shut down all of CAL FIRE’s seedling nurseries in the early 2000s, just as more than 150 years of fire suppression and climate-driven declines in forest health began fueling megafires in the West on a scale never seen before. All of California’s largest wildfires — and virtually all of its most deadly and destructive ones — have occurred since 2000.

CAL FIRE reopened the seedling nursery at the Moran Center a few years ago, and its small staff now produces about 250,000 tree seedlings annually for distribution at low cost to private landowners who need to replant anywhere between 20 and 5,000 acres.

Douglas fir seedlings. Photo: Janet Byron

Byrd says the amount of seedlings CAL FIRE currently produces is a “drop in the bucket” compared with replanting needs for smaller forested areas. The agency now has plans to add more cold storage for tree seeds and ramp up its nursery capacity to a million tree seedlings per year.

“To avoid permanent loss of our forests, it’s really important to act quickly,” Byrd says.

Collecting & Storing Seeds

To grow millions of tree seedlings, nurseries need seeds. Oaks and conifers produce the most seed during what’s known as mast years, when trees have a bumper crop of cones, acorns, and seeds. “We survey the forests every year, because we never know when it’s going to be a big cone year,” Byrd says. (Acorns must be collected and sown in the same year.)

During mast years, teams of tree climbers rush out to identify healthy, dominant trees for collecting cones. CAL FIRE and the Forest Service partner with the nonprofit American Forests to train seasonal tree climbers for this statewide effort. Tree climbers must collect cones from the top of the tree down to avoid self-pollination, and cones must be transported back to the Moran Center quickly for processing. “We want to make sure that we’re starting off with the best seed,” Byrd says.

When cones arrive at the Moran Center, they’re dried on large racks in bushel bags, then dumped into a huge hot-air kiln, which helps to open up the cones. Next they’re lifted into a hopper, which tumbles the cones and knocks out the seed, followed by de-winging and sorting seed with hand screens and air separators, depending on the species. “It’s a kind of long, kind of tedious process,” says Allison Veiga, CAL FIRE forestry technician.

Finally, seedlots are stored in the facility’s on-site freezer under carefully controlled temperature and moisture levels. “If our math is off, too many seeds will reabsorb moisture, and the seedlot will be ruined,” says Marisol Villarreal, CAL FIRE assistant seed bank manager. “It’s like putting a soda can in the freezer. We want to avoid that.”

In April, the center starts taking seedling requests for the following year’s replanting season, which runs from November to May. Seeds are retrieved from cold storage and sown in Styrofoam trays, where they germinate and grow in climate-controlled shade houses and greenhouses.

“Our germination tests show that seed collected in the 1960s is still viable,” Byrd says, although the percentage of older seeds that germinate declines every year.

Forests for the Future?

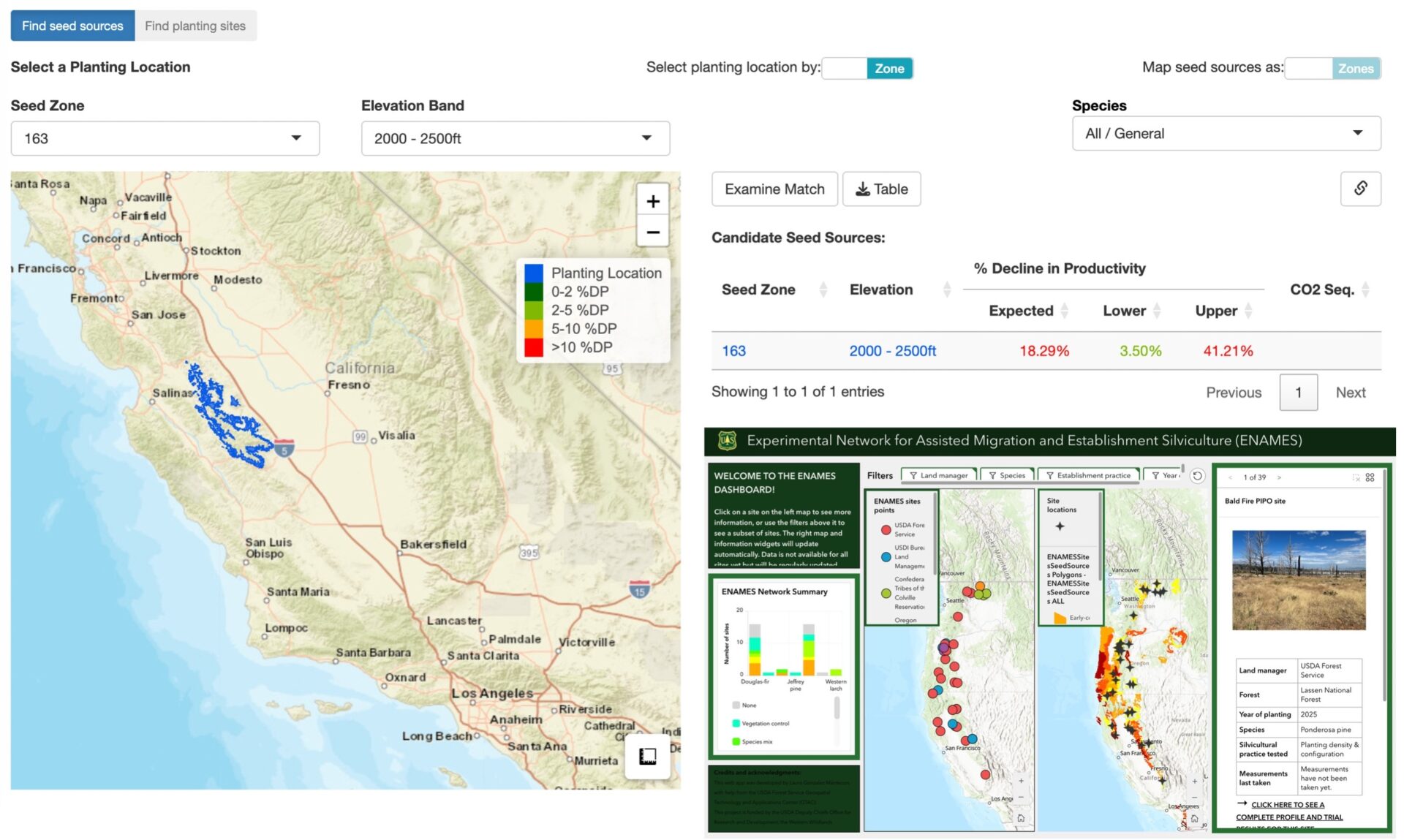

To help reforestation managers make planting decisions for forests that will mature in two or three decades, researchers with the Forest Service, Oregon State University, and Conservation Biology Institute released the online seedlot selection tool in 2016 to help match optimal seedlots with replanting sites based on current or future climate scenarios.

While useful, the seedlot selection tool “assumes that trees in different ecozones are best adapted to the area where they’re currently growing, and does not consider factors such as aspect, slope, and competitive environment,“ says Stewart, who led the development of the next-generation climate-adapted seed tool (CAST) to help identify seed sources that are best adapted to local growing conditions.

Screen shots of two tools: CAST and ENAMES.

And plant scientists are using these seed tools to conduct long-term common-garden experiments, where seedlings from different seedlots are planted at different elevations and monitored year by year for survival and growth. The largest common-garden study currently underway is the Forest Service’s Experimental Network for Assisted Migration and Establishment Silviculture project.

Assisted migration is “the movement of seed sources of populations … to new, currently cooler locations within their habitat range,” the project website explains. “The goal is to match the seed source to a site where it will survive in a future climate, without moving it so that trees suffer cold damage in the near term.”

The project’s network of 30 experimental sites, spanning from southern California to northern Washington, will test the effectiveness of basing replanting decisions on the seedlot selection tool or CAST under different climate scenarios. The last plots were planted this year, so results are a few years off.

Predicting Future Forest Function

UC Merced associate professor Emily Moran (no relation to Lew Moran, first director of the California Department of Forestry) received a $900,000 UC climate action grant to study how well CAST predicts the survivability of tree seedlings at 11 planting sites in the Sierra Nevada. “We want to understand how far you can transfer seedlings to higher elevations and still have them perform well in the near-term,” she says.

In the early 2010s, Young teamed up with a Forest Service group that had recently planted common-garden sites on national forest lands in the Sierra Nevada that had burned in high-severity fires. Early results from the planned long-term study suggest that moving seedlings provenanced from lower elevations to higher ground is a winning replanting strategy. In an analysis of data from sugar pines, Moran found that seed sources from lower elevations or south of planting areas performed as well as or better than local sources, while those from colder, wetter, or higher areas did worse. Because everywhere is getting warmer, seeds adapted to warmer locations are better prepared for historically colder places.

Photo: Janet Byron

“This should boost the confidence of federal and state land managers that they can make use of tools like CAST to improve future forest function without seeing a big drop in near-term reforestation success,” Moran says.

Ironically, in just the past five years, fires have destroyed three of four experimental planting sites, forcing the study to an abrupt end.

“The goal was for this study to exist indefinitely, and the longer the trees survived the more useful it would be,” Young says. “Trees are long-lived organisms, and we need to know how they’ll respond to climate decades into the future.”

MORE

- Seeding Citizen Scientists, KneeDeep, July 2022

- Seeding Urban Gardens with Love, KneeDeep May 2024

- CAL FIRE Reforestation Services

EXTREMES-IN-3D

SERIES CREDITS

Managing Editor: Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Web Story Design: Vanessa Lee & Tony Hale

Art Director: Afsoon Razavi

Science Advisors: Alexander Gershunov, Patrick Barnard, Richelle Tanner, Emily Corwin, Terry Young

Series supported by the CO2 Foundation.

Top Photo: Seedlings at the Moran Reforestation Center in Davis are used to replant forests after wildfires. Photo: CAL FIRE