Ladder fuel on the forest floor accelerates fire. Photo: Steve Kuehl

Insurance Innovations Reward Communities Trying to Reduce Climate Risk

As climate change continues to accelerate, it’s becoming clear that disaster insurance in the U.S. can’t keep up. Providers are starting to move out of wildfire-prone regions in California and floodplains along the East Coast, leaving homeowners in a bind when disaster strikes. But some organizations are reimagining what insurance could be. Rather than focusing on individual homes or possessions, these programs take the severity of the disaster into account — as well as community efforts to mitigate risk. Now, one California town has adopted the first community wildfire insurance policy that rewards nature-based solutions in its premium, opening the door for a potential new era in climate insurance. Other programs are starting to think along similar lines, including a Florida town looking to pilot an insurance exchange program with a California partner and a New York City plan that pays low-income neighborhoods when floodwaters rise too high.

Extremes-in-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

FULL READ

Insurance Innovations Reward Communities Trying to Reduce Climate Risk

Nestled in the Sierra Nevada mountains between Lake Tahoe and the site of the infamous Donner party encampment, Truckee, California is a ski town best known for trees and snow. But once the snow melts, the pines become a wildfire liability. In response, Truckee is spearheading what just might be the future of wildfire insurance.

Jason Hajduk-Dorworth is no stranger to fire hazards. The former Santa Cruz fire chief spent three decades in emergency services before retiring to Truckee in 2024, where he now serves as an administrative director for the Tahoe Donner homeowners association, which encompasses 6,500 homes in the greater Truckee area. Over the course of his career, Hajduk-Dorworth has watched wildfire risks rise from a remote possibility to a real and present danger. At the same time, he’s seen insurance companies begin to retreat from forest-adjacent California communities.

“People can’t get insurance, or insurance is really expensive and they’re getting dropped,” he says. So he started applying his firefighting expertise to a new department: insurance risk reduction.

Lay of the land around Truckee. Photo: Brandon Huttenlocher

The Tahoe Donner Association has, for decades, worked to lower the odds of a catastrophic fire by carefully managing more than 1,000 acres of surrounding forest and creating defensible space around homes. But insurance rates didn’t take that work into account. So the association collaborated with the Nature Conservancy, risk analytics agency Willis Towers Watson, Globe Underwriting, and the University of California, Berkeley to craft a new plan.

This year, their efforts paid off. In May, Truckee and the greater Tahoe Donner area scored the first community wildfire resilience insurance policy in the United States to reward effective forest management in the cost of the policy. The agreement represents an encouraging acknowledgement by insurers that community adaptation can have a measurable – and financially beneficial – impact.

As global climate change continues to turbo-charge storms, shift rainfall patterns, and worsen the risk of everything from lightning strikes to wildfires to tornadoes and even earthquakes, it’s becoming increasingly clear that traditional insurance models can’t keep up. So far this year, California insurance providers have paid more than $20 billion to wildfire survivors in Los Angeles County alone. That kind of risk has led many major companies to hike the price of disaster insurance to an untenable degree in flood- or fire-prone regions — or, in some cases, cease to offer coverage altogether. Even when homeowners do have coverage, their plans often come up short: they don’t cover shared neighborhood assets, or they don’t help with immediate costs before the damage is assessed.

EXTREMES-IN-3D

A seven-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Series Home

Click here to enter

Part 6: Infrastructure

Part 7: Aftermath

Supported by the CO2 Foundation.

The January 2025 wildfires in Los Angeles destroyed more than 18,000 structures. In Altadena (above after the Eaton Fire), long home to middle class Black and Latino communities, many homes lacked sufficient insurance to rebuild. Photo: Mark Holtzman, West Coast Aerial

The Tahoe Donner Association has now joined a growing group of neighborhoods, nonprofits, and cities taking out plans designed to help communities build back more quickly after disasters. Rather than focusing on one family or individual’s property, community insurance underwrites a whole city, town, or forest.

Some of those plans also aim to help communities build better along the way, incorporating climate adaptation incentives into the price. They especially reward responsible land stewardship efforts, such as prescribed burns in fire-adapted forests or wetland restoration along stormy coasts. They could very well represent the way forward for disaster insurance — but only if enough communities and insurance providers buy in.

The Understory: Science Over Stuff

Until recently, large, out-of-control blazes tended to occur far away from major residential areas. Massive disasters like the 2018 Camp Fire in and around Paradise, California, which killed 85 people and destroyed more than 18,000 structures, served as a climate alarm bell for wildfire risk.

“Up until about six or seven years ago,” says Mike Beck, director of UC Santa Cruz’s Center for Coastal Resilience, “fire risk wasn’t a major consideration” for many insurance providers. But the paradigm is shifting — fast.

The groundwork for today’s wildfire landscape was laid well over a century ago. Large fires, often caused by lightning strikes, have always been a part of Sierra Nevada ecology. And tribes like the Washoe, who have lived around Lake Tahoe for thousands of years, have long used smaller-scale burns to cultivate plants. But as American colonizers pushed westward, they forced tribes off their lands and outlawed cultural burn practices. They also suppressed large forest fires – first to protect logging interests, then in an attempt to protect infrastructure in growing cities and towns.

Photo: Steve Kuehl

The woodlands slowly turned into tinderboxes, and climate change made matters worse.

“Our western forests — and other forests — are now choked with fuel,” says Dave Jones, director of the Climate Risk Initiative at UC Berkeley. “So when there’s an ignition, the fire doesn’t stay on the ground like it used to 120 years ago.” Blazes that would have once quietly burned themselves out along the forest floor can instead climb to the treetops and spread catastrophically.

The Camp Fire, sparked by a poorly maintained powerline, erupted during the Southwest United States’ longest dry spell in at least 1,200 years. Drought and excess heat dehydrated wood and brush, leaving the forests extremely flammable. Warmer temperatures have also extended the range of certain bark beetle species, which have killed off (and subsequently dried out) millions of additional trees throughout the Sierra Nevadas.

Insurance providers are struggling to keep pace with the growing intensity and frequency of forest fires across the Western U.S. Rather than risk losing millions or even billions of dollars, some companies have simply stopped issuing homeowner’s insurance in states like California.

Photo: Steve Kuehl

The Tahoe Donner Association’s plan doesn’t replace homeowner’s insurance or impact insurance rates for HOA members, but by incorporating community adaptation efforts into the costs, it reflects a growing area of innovation.

Before many Northern California towns knew to take fire seriously, Truckee residents were working on defensible space. Folks living in Tahoe Donner had been engaging in forest management since the 1970s, but their wildfire wakeup call came in 2007, when a blaze came too close for comfort

The project picked up in earnest in 2015 when the homeowners association got involved. With guidance from UC Berkeley scientists and knowledgeable community members, residents began removing downed trees, thinning underbrush, and strategically rearranging fuel so that if (and when) it does burn, the fire is confined to one area.

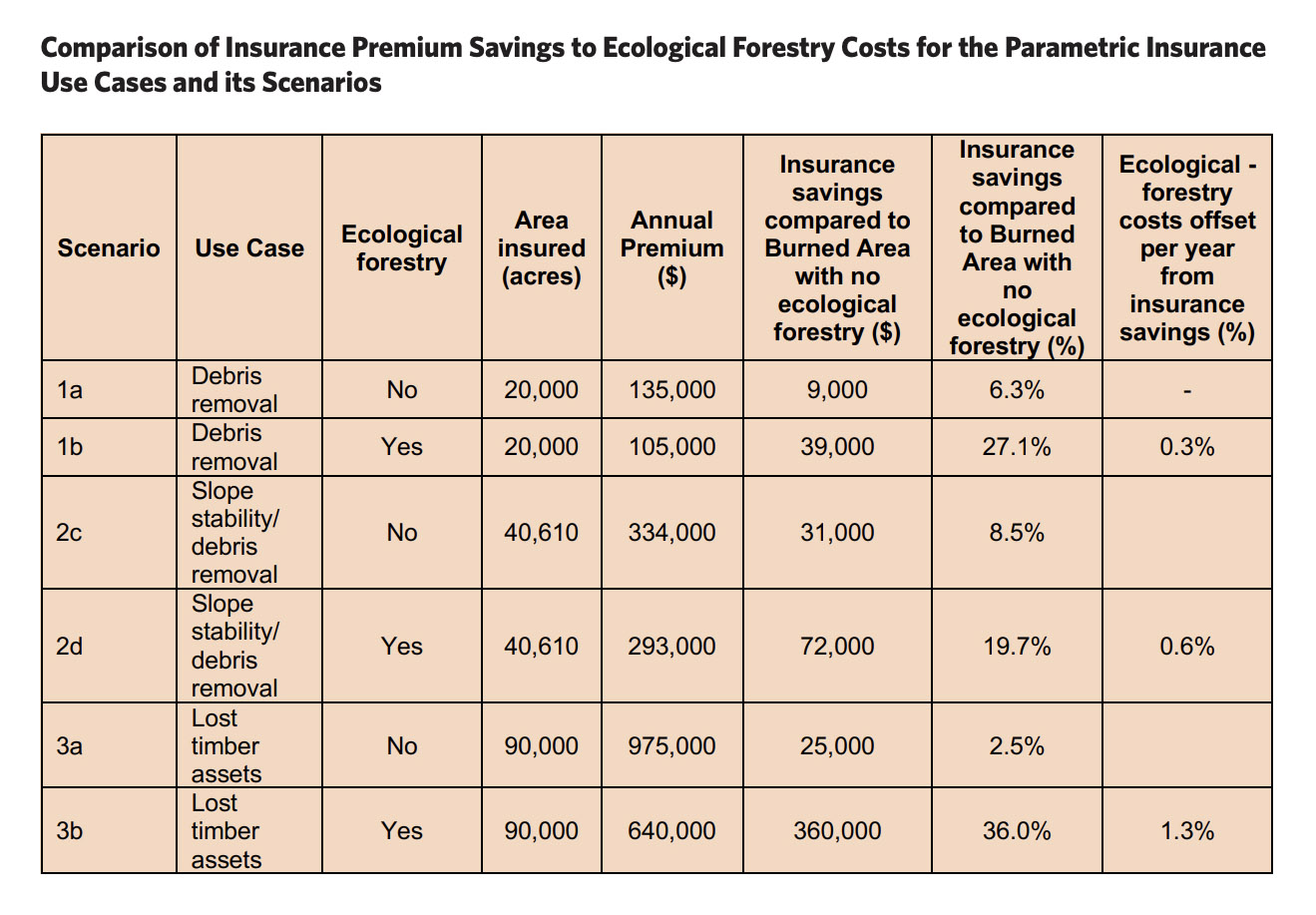

A 2021 white paper co-authored by the Nature Conservancy and Willis Towers Watson estimated that these efforts reduced the chances of wildfire damage by 20-40% annually. “That’s a big deal,” says Jones, who is himself a Tahoe Donner homeowner.

This data was sufficient to convince an insurance company to underwrite the $2.5 million policy, reducing the rate it would normally charge by nearly 40% and lowering the deductible by almost 90%. “It requires, you know, a lot of work. And so having that accounted for in the rate is a motivator,” says Kristen Wilson, a forest scientist with the Nature Conservancy.

Source: Nature Conservancy & Willis Towers Watson, 2021

Tahoe Donner’s policy, like many community-level disaster policies, uses a parametric, rather than indemnity, model for payouts.

The traditional indemnity model of insurance works by reimbursing policy holders for stuff — a home, a painting, cars, furniture, assorted electronics, etc. Damage to these items in a disaster triggers a payout (at least in theory). The policy holder then has to prove their things were destroyed. If they can’t verify the damage to the insurance company’s satisfaction, they might not get reimbursed.

Parametric insurance, in contrast, works by paying out based on quantifiable benchmarks. In the case of natural disasters, those benchmarks can be numbers like wind speed, wave height, earthquake magnitude, or acres scorched in a wildfire, rather than couches or cabinets gone up in flames. That doesn’t mean nature-based solutions can’t work with indemnity insurance, says David Williams, a Willis Towers Watson associate director. But parametric plans typically cover a geographic area rather than an individual home or vehicle, which can make it easier for a whole community to get on board.

Another distinct feature of the Tahoe Donner policy is the fact that the 1,300 acres it covers are maintained by a homeowners association.

“Because we’re an HOA, we have a little bit more leverage [with people living there] than other communities,” says Hajduk-Dorworth. That dynamic makes it easier to make sure people keep up their fire management practices. “If you’re going to live here, there are requirements for being a steward.”

The Overstory: Parametric Planning

Parametric insurance isn’t just for HOAs, however. Another pilot program in New York City, operated through the nonprofit Center for NYC Neighborhoods, will disperse funds to low-income homeowners who experience financial hardship after a catastrophic rainfall event — though so far, it hasn’t paid anything out yet.

According to program manager Theodora Makris, parametric funds can pay out more quickly than traditional homeowner’s insurance, and community-level plans can be a helpful addition. Funds can be applied “to the full range of needs that homeowners face, whether that’s to pay your mortgage or hire a babysitter or take time off work to muck out your house,” she says.

“Stuff” resets the scene after the Camp Fire of 2018 in Paradise, California. Photo: Florence Middleton

The model is picking up steam in California as well. In September 2024, the City of Fremont in the Bay Area put what may be the state’s first city-wide parametric flood insurance plan in place. A month later, the State of California announced that it would help pay for a similar plan for the City of Islington in the Sacramento delta. That plan will pay out if floodwaters reach a certain depth.

Tahoe Donner’s plan takes parametric insurance a step further, tying it to nature-based climate adaptation measures. In the past few years, both the State of California’s Climate Insurance Working Group and the Wharton School of Business have recommended such an approach, which can reward adaptation with affordable premiums while supporting efforts to plan ahead.

But tying insurance to nature-based solutions is no easy task. It requires understanding big-picture climate risk and hyper-local adaptation efforts well enough to put numbers on both.

“For us to calculate these impacts, it required a lot of custom modeling of the specific area. And big insurance companies cannot afford to do that with every little community here and there,” says Guillermo Franco, managing director and head of catastrophic risk research at the reinsurance firm Guy Carpenter. For now, that cost can be prohibitively expensive at the homeowner’s insurance level, but it can work for larger community-scale plans, he adds.

Tahoe Donner’s plan is a good example. The Nature Conservancy white paper demonstrated that the climate models typically used by insurance companies can account for adaptation measures taken for wildfire risk. And nature-based risk reduction measures could also work for other types of climate disasters, Jones says.

Tahoe-Donner efforts to preserve the resilience of trees and surrounding communities to fire (before and after clearing a tinderbox of underbrush). Photo: Brandon Huttenlocher

While Southern California has a long history of frequent post-fire debris flows, Northern California (apart from some Central Coast slides), is essentially uncharted territory for these events. “I grew up in Southern California, and we had fire season and debris flow season, but you rarely heard about fires in other parts of the state,” says Patrick Barnard, a USGS coastal geologist. “Now, fires and post-fire debris flows are happening elsewhere in the state every year.”

2021 was particularly bad, with massive flows along the Central Coast and in the Sierra Nevada. In January, an atmospheric river set one off on the River Fire burn scar above Salinas, damaging dozens of homes and trapping people inside. The same storm caused even bigger flows on the Dolan Fire burn scar in Big Sur, including one that tore out 150 feet of Highway 1, leaving it impassable for months.

Storm surge combined with atmospheric rivers of rain in December 2024 swept waterfront buildings into the Pacific Ocean in Santa Cruz, California. Photo: Steve Kuehl

Franco hopes that by directly insuring each other, communities will be incentivized to model and understand their own climate risk. Currently, he says, many communities don’t. But in a reciprocal exchange, a community “steps into the shoes of an insurer. They’re going to find themselves on both sides of the equation.”

In the best-case scenario, Franco says, partners could spur each other to action. If one partner argues for a discount for better forest management, a partner facing hurricane risks might decide to model their own adaptation options. “We’re also going to do the same with our bays, with our mangroves, with our cays,” says Franco. “And that is a healthy process.”

A reciprocal exchange could provide flexibility. Communities could decide, for example, to give a portion of the money paid into the program back to the participating cities to use for climate adaptation after a certain number of years if a disaster fails to strike. The pilot is set to launch next year in Sarasota, Florida and an as-yet unspecified town in California.

Laurel Meadows community in Sarasota, Florida after Hurricane Debby in 2024. Photo: Bilanol, I-Stock

Of course, none of these models can fully replace emergency disaster aid from state programs and federal agencies like FEMA, or prevent people from taking out individually-held policies. And all of them are useless without individual and insurance agency buy-in. The biggest hurdle that community-managed solutions face is simply getting all parties to commit. But being able to show tangible risk reduction using verified climate models goes a long way in building trust.

“We have to agree on some sort of standard so that everyone has a little bit of skin in the game,” says Hajduk-Dorworth. Because these policies are still so new and so rare, though, it may be hard to convince people until they’ve seen them succeed.

There’s another potential issue brewing for parametric plans, as well. Currently, many policies rely on data from organizations like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to determine the scope and scale of a given disaster. But the Trump administration is in the process of gutting these agencies, leaving their futures uncertain.

According to estimates from the American Geophysical Union and The Planetary Society, USGS could lose a staggering 39% of its funding, and NASA’s 2026 budget could be slashed by nearly 25%. Likewise, NOAA faces a 14% federal budget cut for 2026, with most of the pruning focused on climate and weather labs.

If these agencies no longer provide data, it would make it much harder for insurers to determine when a disaster should trigger a payout.

“That is certainly a risk,” says Franco. But there are other organizations collecting the relevant data, he says. The European Union has a satellite network called Copernicus, for example, that monitors storms and wildfires globally. And local seismological centers could fill in information on earthquakes — assuming all parties agree to the exchange.

Tahoe Donner’s policy is based on satellite data collected by the European Space Agency, so its future payouts are protected from that standpoint at least. Time will tell how effective the program turns out to be — though the fact that it exists at all is cause for excitement. “This is the first crack in the insurance world’s armor that I’ve seen,” says Hajduk-Dorworth.

Santa Rosa’s Coffey Park neighborhood today, eight years after the Tubbs Fire (top video in 2017). Video: Rose Garrett

It may be that there’s no one-size-fits-all model for alternative disaster insurance; each policy may need to be tailored to the needs of a particular locale. Undoubtedly, this will involve more investment from all parties involved — insurance providers, risk assessment specialists, and the community members themselves. But the end result could be a more robust and eco-friendly insurance landscape.

“The more you engage with communities and the people on the ground, as it were,” says Beck, “the more likely it is that you’re going to find solutions.”

EXTREMES-IN-3D

SERIES CREDITS

Managing Editor: Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Web Story Design: Vanessa Lee & Tony Hale

Art Director: Afsoon Razavi

Science advisors: Alexander Gershunov, Patrick Barnard, Richelle Tanner, Emily Corwin, Terry Young

Series supported by the CO2 Foundation.

Top video: Coffey Park neighborhood in Santa Rosa after the 2017 Tubbs Fire by Jak Wonderly.