Tears for Trees

Pickup passing the severed limbs and body parts of an ancient oak under the Redwood Road power line in Napa County. Photo: Ariel Okamoto.

My family sold a property in the Napa wildland interface in 2019 and it felt like we got lucky. After forty years and two generations on the ridgetop, we were land rich and cash poor, and after the 2017 firestorm all around us it was clear it would take heaps of money to weather the future in this at-risk corner of the wine country.

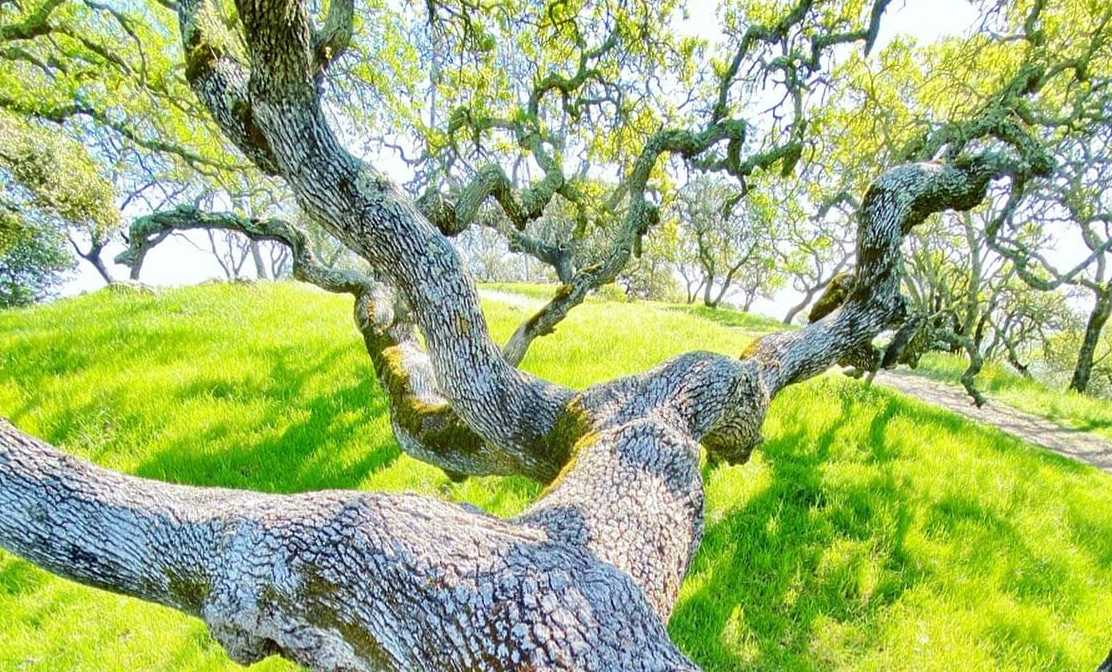

Since we stayed on in one house as renters, however, I’ve been able to observe first-hand the army of white trucks topped with cranes and chippers deployed to remove the oaks, redwoods, bays and manzanitas from around the power lines on our mountain. The main access road to the big asset at the end — the Christian Brothers monastery and the Hess-Persson winery — got a lot of attention from this steamrolling vegetation management machine. The proximity of that asset probably saved our little property in 2017. Clearing and fire proofing on a landscape scale after that could save it in the future. Regardless, it’s still heartbreaking to see 200-hundred-year-old oaks in heaps and lopsided redwoods — limbless on one side, fully branched on the other, like a wire brush.

Redwood grovelet reduced by half in Napa County. Photo: Ariel Okamoto.

I asked PG&E for some numbers on what they’ve been up to in what they call “High Fire-Threat Districts” across Napa County. According to their North Bay spokesperson Deanna Contreras, PG&E spent approximately $1.06 billion dollars in 2019 and $1.4 billion in 2020 on vegetation management programs along transmission and distribution lines across Central and Northern California, which included routine and compliance work, work to mitigate trees impacted by the drought and bark beetle infestation, and work in high fire-threat areas. They have also granted nearly $17 million to local Fire Safe Councils since 2014, including the Napa Firewise Foundation.

Of course, I know that this great tree slaughter is all in the interests of public safety and fire safety, and that our human development of these landscapes has prevented historic natural fire in ways that could have prevented the current culling. And I also know that when power lines blow down on a red flag day, the results can be deadly and costly, and that nonetheless people resent the public safety power shutoffs.

Other Recent Posts

Slow Progress on Shade For California’s Hottest Desert Towns

Coachella Valley communities face record temperatures with little shade. Policy changes lag as local groups push for heat equity.

In Uncertain Times, the Port of Oakland Goes Electric

A $322M grant powers Oakland’s port electrification — cleaning air, cutting emissions, and investing in community justice.

Testing Adaptation Limits: Mariposa Trails, Marin Roads & San Francisco Greenspace

In KneeDeep’s new column, The Practice, we daylight how designers, engineers and planners are helping communities adapt to a changing climate.

ReaderBoard

Once a month we share reader announcements: jobs, events, reports, and more.

Boxes of Mud Could Tell a Hopeful Sediment Story

Scientists are testing whether dredged sediment placed in nearby shallows can help our wetlands keep pace with rising seas. Tiny tracers may reveal the answer.

“I Invite Everyone To Be a Scientist”

Plant tissue culture can help endangered species adapt to climate change. Amateur plant biologist Jasmine Neal’s community lab could make this tech more accessible.

How To Explain Extreme Weather Without the Fear Factor

Fear-based messaging about extreme weather can backfire. Here are some simple metaphors to explain climate change.

Live Near a Tiny Library? Join Our Citizen Marketing Campaign

KneeDeep asks readers to place paper zines in tiny street libraries to help us reach new folks.

Join KneeDeep Times for Lightning Talks with 8 Local Reporters at SF Climate Week

Lightning Talks with 8 Reporters for SF Climate Week

Staying Wise About Fire – 5 Years Post-CZU

As insurance companies pull out and wildfire seasons intensify, Santa Cruz County residents navigate the complexities of staying fire-ready.

We will be seeing those white trucks, both PG& E and their contractors, in our neighborhoods and on our rural roads for decades to come no doubt. According to Contreras, PG&E prunes or cuts down more than 1 million trees annually to maintain clearance from powerlines.

Everyone blames PG&E for poor maintenance and fire losses but rarely owns our own addiction to electricity as a root cause. We want that electricity, that high-speed internet, and we deserve it, right? Even if we live in a remote fire-prone canyon down a dirt road in the coastal mountains. On our buzz cut ridgetop, I mourn the trees.

Healthy blue oak in Rockville Hills Regional Park in Fairfield, near the eastern extent of the 2017 Atlas Peak Fire. Photo: Robin Meadows.