Retreat By Any Other Name

To prepare for the ocean moving in, many waterfront structures will have to move out. But don’t call it “managed retreat.”

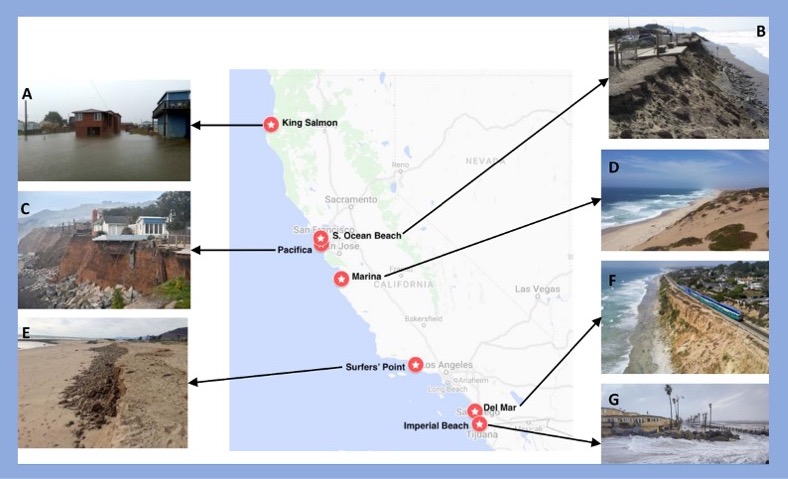

It’s one of many conclusions a group of scientists drew from a study of how seven Californian towns and cities tried to plan for rising seas, with wildly different results.

“Retreat can conjure failure, and nobody wants to be managed,” explained the study’s corresponding author Amanda Stoltz at the California Social Coast Forum this March. Part of the problem is the term itself. One Pacifica resident quoted in the study commented, “Managed retreat’ is a code word for give up — on our homes and the town itself.”

Managed retreat from sea level rise, or planning to move property and infrastructure to higher ground, elicited strong opposition from four of the communities Stoltz and her coauthors examined. But the practice was accepted, even embraced, in three others.

The seven locations where a team of scientists examined reactions to managed retreat planning. Source: Stoltz et al., 2021.

Affluence often aligns with stronger resistance to relocation. But an even stronger factor could be how much private versus public land is imperiled. In wealthy San Francisco, a lengthy process of negotiation triumphed with a plan for managed retreat of a beloved public beach, while residents of the remote northern town of King Salmon rallied against the suggestion of relocating from their homes. Nearly three-quarters of the town qualifies as “economically disadvantaged” by federal criteria.

Acceptance of managed retreat also hinged on how early in the planning process community members were consulted. Consistent communication reaped fruitful agreements in places like Marina in Monterey County, but fell through in Imperial Beach near San Diego, where fearful, conspiracy-tinged messaging infected the discourse faster than local officials could get ahead of it.

The importance of language choice cropped up in almost every location. One conservative retreat-resistant town had residents who didn’t approve of the term “sea-level rise,” although they acknowledged that flooding had grown vastly more common over time. In Del Mar, a wealthy seaside enclave with a renowned racetrack, the term “managed retreat” was scrubbed from the policy docket after vociferous public opposition — yet part of their adaptation plan states, with no apparent trace of irony, that they will monitor flooding frequency to determine whether it “is becoming unsustainable to rebuild in the same location.”

Since the study was published, Stoltz has noticed more chatter about managed retreat (or ‘graceful withdrawal,’ as she suggests calling it.) A recent bill supporting revolving loan funds for municipalities to buy threatened properties died on the governor’s desk, with Newsom insisting on a more integrated state-level approach to the issue. Regardless of how sea-level rise policy progresses, Stoltz hopes that planners will take note of their neighbors’ early successes and failures as more municipalities confront what to do about the half-million California homes in the path of the rising sea.

“You can’t just go in with solutions and think that they’re going to be accepted,” she says. “Even if the science is really strong.”

Other Recent Posts

Assistant Editor Job Announcement

Part time freelance job opening with Bay Area climate resilience magazine.

Training 18 New Community Leaders in a Resilience Hot Spot

A June 7 event minted 18 new community leaders now better-equipped to care for Suisun City and Fairfield through pollution, heat, smoke, and high water.

Mayor Pushes Suisun City To Do Better

Mayor Alma Hernandez has devoted herself to preparing her community for a warming world.

The Path to a Just Transition for Benicia’s Refinery Workers

As Valero prepares to shutter its Benicia oil refinery, 400 jobs hang in the balance. Can California ensure a just transition for fossil fuel workers?

Ecologist Finds Art in Restoring Levees

In Sacramento, an artist-ecologist brings California’s native species to life – through art, and through fish-friendly levee restoration.

New Metrics on Hybrid Gray-Green Levees

UC Santa Cruz research project investigates how horizontal “living levees” can cut flood risk.

Community Editor Job Announcement

Part time freelance job opening with Bay Area climate resilience magazine.

Being Bike-Friendly is Gateway to Climate Advocacy

Four Bay Area cyclists push for better city infrastructure.

Can Colgan Creek Do It All? Santa Rosa Reimagines Flood Control

A restoration project blends old-school flood control with modern green infrastructure. Is this how California can manage runoff from future megastorms?

San Francisco Youth Explore Flood Risk on Home Turf

At the Shoreline Leadership Academy, high school students learn about sea level rise through hands-on tours and community projects.