Grants Underwrite Fire Resistance

“When we took the elders out there they said, ‘You can’t just go burn the land.The fuel load is so high and the density of the trees so great, that it would destroy everything.”

Statewide, the Conservancy received 81 proposals, of which it approved 34 projects. “It’s astonishing that there are that many communities that are already trying to get projects going, have done the planning, done CEQA (California Environmental Quality Act) analysis, and just need resources,” says the Conservancy’s Mary Small. “We prioritized projects that were going to start by August and reduce fire risk in the wildland-urban interface.”

The grants—which range from just under $48,000 to the Santa Clara Valley Habitat Agency for eucalyptus removal and weed abatement at Davidson Ranch Reserve to more than $1 million to the Napa County Resource Conservation District for resilience activities on four publicly-accessible, protected properties on the east side of Napa Valley—showcase diverse strategies for reducing fuel loads and protecting property. Grantees will use both mechanical and biological methods to manage vegetation: the Sonoma County Regional Parks and the Sonoma County Water Agency both received funds for “prescribed herbivory,” the practice of allowing cows, sheep and goats to graze on potential wildfire fuel. Sonoma County has identified grazing as one of eight resilience project types to be prioritized for funding.

“These developments have been in the works for many years, and the projections have changed over time,” explains Loper. In 2012, for example, the upper range of projected sea-level rise for California was 55 inches, or 4.6 feet by 2100. In 2018, the State of California issued revised estimates that now top out at 6.9 to 10 feet by the end of this century.

Dr. Kristina Hill, professor at UC Berkeley’s Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning, isn’t buying it. “There are documents from the 1990s pointing out the sea-level-rise problem,” she says. “Developers and the engineers they hired often chose a middle number, because it sounded reasonable. But they knew [it could be worse].”

Currently each project has the flexibility to choose from the State of California’s high, medium, or low sea-level-rise projections to determine its own risk based on unique site characteristics, lifespan, and consequence. “Not every project constructed today is completely resilient to the flood risk it might encounter in 2100,” points out Ethan Lavine, chief of permits at the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC). “But each is being built in such a way they should be able to adapt to that flood risk when the time comes to do so.” BCDC has rigorously applied sea-level-rise policies requiring that projects be designed to withstand expected 2050 levels and have plans for adapting to 2100 levels.

A few forward-thinking developers have planned for adaptation, acknowledging the need to be ready if the San Francisco Bay rises higher and faster than what they have designed for. Treasure Island, Pier 70, and Mission Rock are committed to monitoring local sea-level rise and developing future plans to improve drainage and shoreline protection as needed. Mission Rock even makes this a component of its shoreline park, with plans for terraced shelves to mark different tidal heights and the upwards creep of the Bay over time. All three projects will use fees generated via a special Community Facilities Districts to help pay for future adaptation measures.

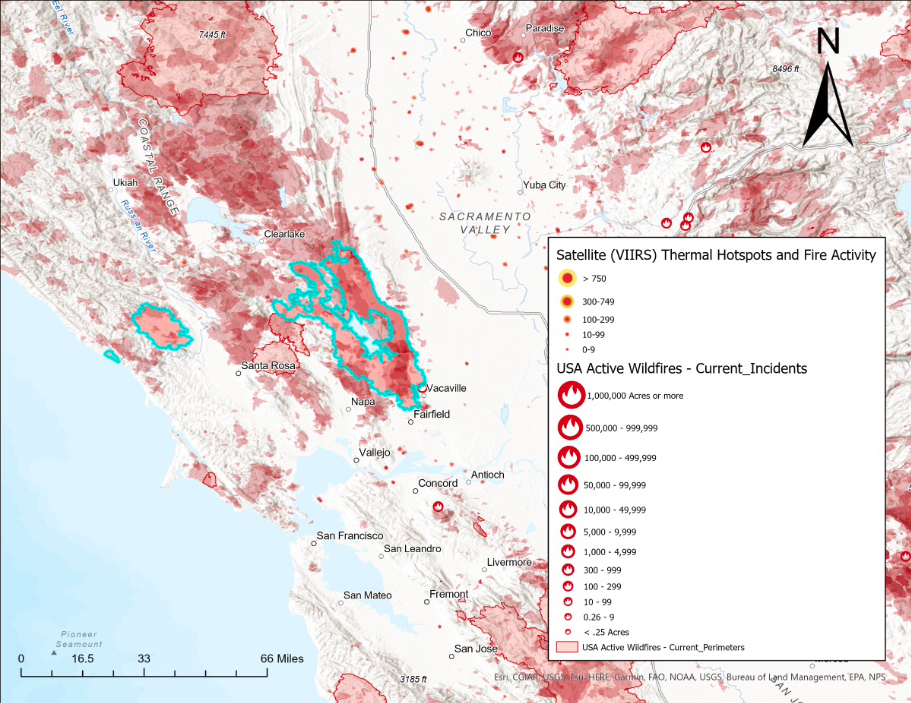

Current wildfire incidents in California, the red shading indicates areas of wildfires in the past. The LNU lightning complex wildfire lands in an area where fires have been common throughout history.

“We use sheep and goats in some locations, and cattle in others, depending on what the goals are,” says Hattie Brown of Sonoma County Parks, which received funding to expand cattle grazing on Taylor Mountain. “For example, in places where we are trying to construct a fuel break in a very small location where we can put up a fence we might put in a bunch of small animals and treat a really targeted area. Whereas we can work on a more landscape scale in some ways more easily with larger animals.” She notes, however, that a number of factors must be considered, including unintended impacts, existing infrastructure, and the potential for predation.

Four California Tribes are among the grantees, including Sonoma County’s Dry Creek Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians, which will receive almost $300,000 to reduce fire-fuels created by the 2019 Kincade Fire and restore approximately 57 acres of the Rancheria. The project will expand a demonstration program meant to bolster the usual methods of fuel management with Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), which relies on restoring native fire-resistant species and traditional methods of managing the oak woodland.

Before and after of clearing fuel load.

The Hennessey and Spanish Fires burn towards Lake Berryessa on August 18, 2020.

Although the Kincade fire damaged the Rancheria, most of the vegetation did not burn, but rather died from the heat, leaving behind acres of standing dead fuel and creating ideal conditions for invasive species to colonize the former oak woodland. When tribal elders were consulted about the demonstration project, they pointed out that these conditions, combined with decades of forest mismanagement, had left the area incompatible with traditional approaches to land stewardship. “We did not expect that at all when we started the project,” says Rancheria Environmental Director Christopher Ott.

Ott cites controlled burning as one traditional approach that the elders nixed. “When we took the elders out there they said, ‘You can’t just go burn the land.The fuel load is so high and the density of the trees so great, that it would destroy everything, burn the soil, leave it completely dead. There’s just too much fuel. It’s too far gone.” As a result, Ott says that the project’s first task will be to determine how to return the forest to a state where it can be managed with traditional methods. Ultimately, says Ott, the goal is to create a healthy forest, including restoring soil sterilized by Kincade fire, so that native species can thrive. “A healthy forest is a fire-resistant forest,” he says.

First published in RARA Review, July 2021.