Shifting Tideline Calls For New Coast Guidance

A little-known tenet of California law may play a key role in preserving the state’s beaches—and the public’s access to them—as sea levels rise. It may also encourage retreat from rising waters rather than attempts to hold them off.

With roots that date back to Ancient Rome, the public trust doctrine is a principle embedded in California’s constitution. It holds that certain lands are held in trust by the state for the benefit of the public. These include tidelands, submerged lands, and navigable lakes, rivers and streams.

On May 10, the state Coastal Commission unanimously adopted a new Public Trust Guiding Principles and Action Plan, which sets forth its approach to carrying out the public trust doctrine in the age of climate change. The guidance doesn’t expand or change the Commission’s existing authority, says the Commission’s Awbrey Yost. Rather, it provides direction for how the Commission should make decisions.

Along the coast, public trust lands are generally located on the ocean side of the mean high-tide line. The new guidance focuses on the tidelands between the mean high-tide line and the median low-tide line, says Yost.

“What’s interesting about the public trust boundary is that it’s generally ambulatory,” says Yost, explaining that the mean high-tide line moves as the shore erodes and grows. “In California, beaches tend to erode in the winter, so the mean high tide line moves landward, but in the summer, as beaches accrete more sand and get wider, the mean high-tide line moves seaward.”

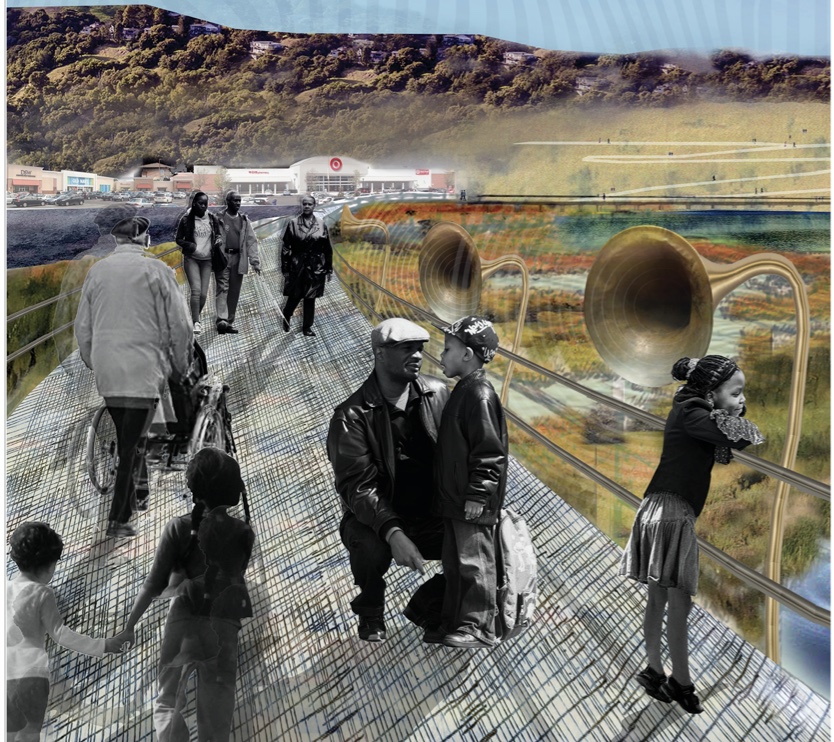

A Distant Shore, #14. Art: Nicholas Coley.

As sea levels rise so will mean high tides, with implications for which lands are covered under the public trust doctrine. “In a lot of places, the public trust boundary will move landward,” says Yost. Determining the location of that boundary will be critical to protecting public trust lands and public access.

The new action plan aims to make the official boundaries of California’s public trust lands more accurate. It calls on the Coastal Commission to work with the State Lands Commission and others to explore alternative ways of determining the mean high-water line.

Currently, the Coastal Commission relies on the method used by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which uses the average of high tide lines over 19 years and is only updated every 20-25 years. The plan notes that as sea-level rise accelerates, “an average based on data from past years will be less and less reflective of present-day high tides.” It commits the Commission to exploring ways to determine a more current mean high-water line. A related provision of the plan calls for evaluating new technologies to locate the boundary between public tidelands and private uplands.

“This is one action that I think has huge potential,” says Ralph Faust, who served as the Coastal Commission’s chief counsel from 1986 to 2006, and who offered comments at the meeting. “We have the ability now with satellites and other technologies to do things that we couldn’t in the old days. Hopefully, with these new technologies we can get much quicker access to knowledge about where the boundary lines are between private property and public property.”

Above Baker Beach #178. Art: Nicholas Coley.

Rising seas are all but certain to increase the conflict between protecting private property and protecting the public trust. “Hard armoring” with shoreline protective structures (seawalls, riprap, breakwaters, etc.) tends to stop the landward movement of the tides, as well as beaches and coastal habitat, by preventing bluff erosion and sand accretion. These strategies may protect inland private property, but at the expense of the lands that California holds in trust for the public.

“Over time, if the ocean is not allowed to move landward, you’ll end up drowning a lot of beaches and really changing both ecosystems and the public’s ability to use those beaches,” says Yost. “There are likely to be really large ecological impacts as tidelands are changed and possibly drowned in a lot of places.”

The impact of sea-level rise on public trust lands is likely to be enormous. According to a 2022 State Lands Commission report, damages and replacement costs for vulnerable assets on just a fraction of public trust lands could exceed $19 billion by 2100, and natural resources and recreational amenities in these areas could lose over $5 billion in value.

Yost notes that the new guidance is largely focused on “recognizing that decisions regulating development are going to have a very real impact on what happens to public trust lands. So an application for hard armoring, for instance, the Commission needs to consider what kind of impact it will have. Is it going to impact sediment supply? Is it going to cause the beach to narrow? What public access impacts are there? Are there ecological impacts?” says Yost.

Edge of the World #8. Art: Nicholas Coley.

The guidance declares that the Commission decision must be guided by the principle that shorefront property owners “may not unilaterally and permanently prevent the landward migration of public trust lands.” It also calls for nature-based adaptation strategies. These strategies, says the guidance, “are often more aligned with the public trust doctrine than hard shoreline armoring,” because they tend to “better protect public trust uses and values like habitat preservation, access to the shore and waterways, and recreational opportunities.”

In other words, when reviewing development applications, the Commission will consider the impacts that protecting a private home with a shoreline protective device may have on public access and ecosystems.

Faust thinks the principles set forth in the guidance are, “quite good and focus in the right direction” but the actions are a little “nebulous.” He worried that words committing the Commission to ‘consider’ and ‘consult’ and ‘participate’ in various processes do not go far enough.

On the other hand, Surfrider Foundation’s Laura Walsh calls the guidance, “a really big deal and a kind of symbolic moment.” Between the “overwhelming” amount of coastal development underway in California and sea level rise, she sees the threats to the public trust as existential. “We see this guidance document as taking a very strong step in proactively trying to safeguard the public trust.”