Birds, Not Bats, Flock to Burned Oak Savannas

Researchers placed microphones in burned and unburned forests to measure bird and bat activity. Photo: Jackie Mara Beck

In the rolling hills of Mendocino County, roving bands of California quails scratch the soil looking for edible seeds in the grass under gnarled oak trees. These quails, an official symbol of California, abound in the oak savannas that define much of the state. And a new study has found that these native birds also thrive in the presence of a different part of the state’s ecology: fire.

In 2018, the Mendocino Complex Fire burned over 400,000 acres of forest, grassland and chaparral. The study, published in Ecosphere in July 2025, found that in the years following the blaze, nearly all of the bird species that frequently nest in the region’s oak-dotted hills actually preferred areas that had burned. Fires, even megafires, likely invigorate oak savannas, the authors concluded. These grassy woodlands are responding differently to recent blazes than the pine and fir forests of the Sierra Nevada.

California quail. Photo: Dave Harper

For the study, a team of researchers spread a series of microphones throughout the UC Hopland Research Reserve in Mendocino County to listen for the birds and bats that call the area home. They placed some mics in locations that burned in 2018, and they put others in areas that did not burn. The researchers then analyzed the recordings collected during the spring and summer of 2020, 2021 and 2022 to see which species were abundant and where they lived.

They did not just document which areas had been touched by fire — they also noted how severely the vegetation had burned. In some areas, the fire only consumed grass and small shrubs. In others, the inferno turned trees into charred stumps.

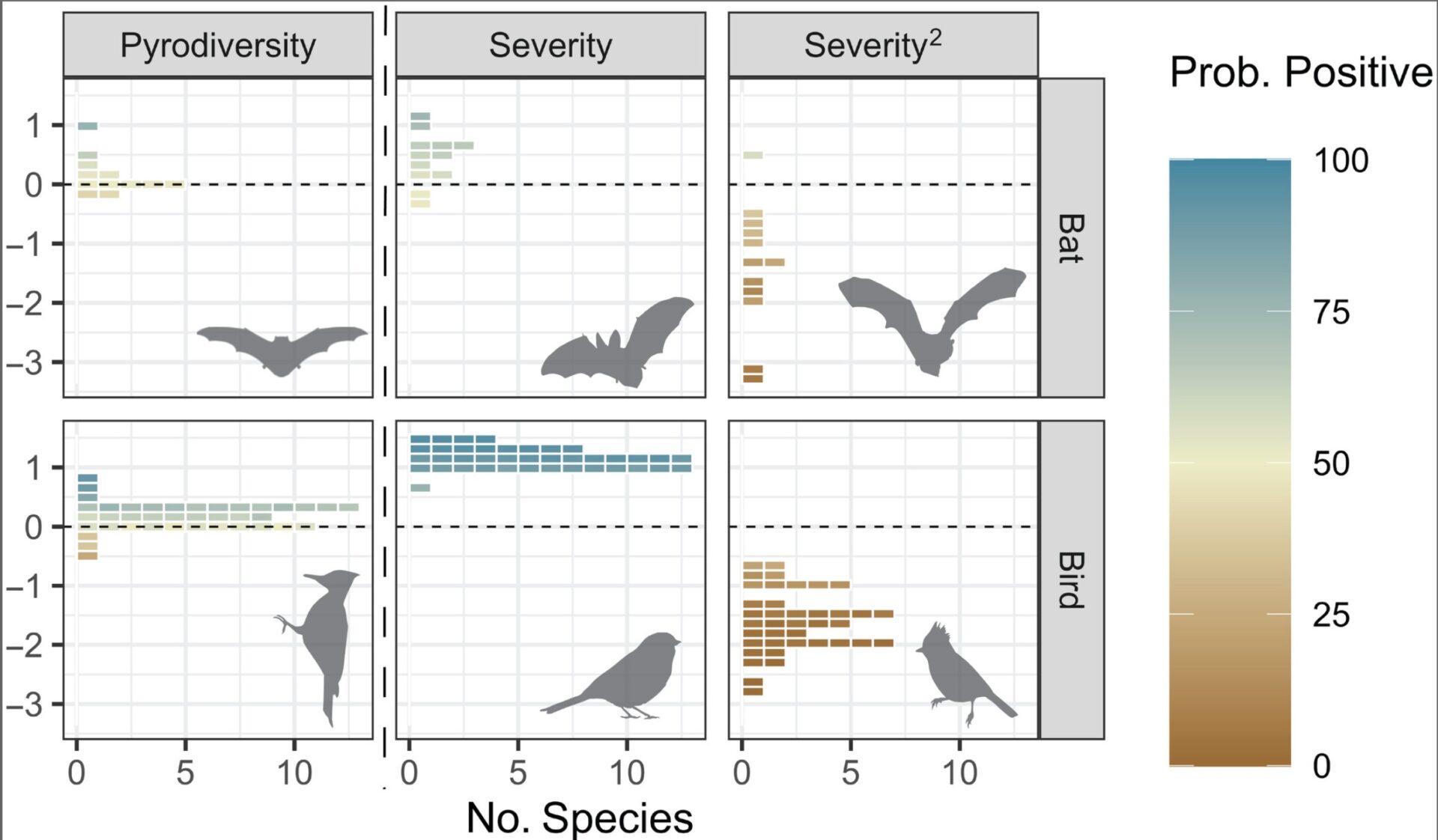

None of the 12 bat species whose echolocation sounds were captured by the microphones showed a strong preference between burned and unburned sites, or different levels of fire. This was unexpected because bats eat bugs, according to study author Kendall Calhoun, an ecologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The downed wood and other burned plant material attracts a lot of insects,” Calhoun says.

Acoustic equipment set up in an unburned area. Photo: Kendall Calhoun

The researchers then analyzed their 17,190 hours of recordings of bird songs and found that 36 of the 39 common bird species preferred areas that burned lightly — even compared to the unburned savanna.

“Fire is an integral part of the ecosystem here,” says Lee Klinger, an independent scientist who works with the department of natural resources of the Esselen Tribe of Monterey County. “It is unsurprising to me that the native birds would respond positively.”

While many of California’s oak woodlands have gone up in flames in recent years, this study is one of the few investigations into their biodiversity post-fire. Earlier research published in 2023 by Calhoun highlighted the resilience of many mammal populations in the years after the wildfire. The new study, however, showed that dozens of bird species did not just persist; they thrived.

Each square represents one of the species (12 bats, 39 birds, and 51 total species) evaluated in the study. The bluer the square, the likelier that species was to congregate in the burned areas. (Pyrodiversity refers to a combination of ecosystem and fire characteristics, while severity refers to how much vegetation burned). Source: Calhoun et al, Ecosphere

“What we saw suggests that fire might have been needed on the landscape,” Calhoun says. “It warrants further investigation of what we can do to best help these habitats and wildlife.”

Although most of the birds benefited from low-intensity fires, a few actually preferred severely burned areas, according to Brett Furnas, an ecologist at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “Different types of fire will benefit different species,” Furnas says. “It’s not a uniform effect.”

Mountain quail, for example, preferred places where the inferno had been hotter. They love the tender grasses and wildflowers that spring up following wildfires.

Even where the blaze had consumed entire trees, the number of new shoots that emerged from their charred trunks surprised Calhoun. Those slender stems will become mighty trees someday, as long as drought or another wildfire doesn’t take them out while they’re small and vulnerable, he says.

But intense fire was uncommon in the oak savanna because the open environment rarely provides enough fuel for tree-killing fires, the researchers found. That’s different from the Sierra Nevada, where fire suppression and climate change have created dense, dry forests that act like kindling when a spark inevitably arrives. Oak savannas are proving resilient so far, they say.

Other Recent Posts

Reforming Rules to Speed Adaptation

Bay Conservation and Development Commission to vote early this year on amendments designed to expedite approval of climate projects.

Warner Chabot Shifts Gears

After 11 years at the helm of the Bay Area’s leading science institute, its leader moves back into the zone of policy influence.

Is Brooklyn Basin Emblematic of Regional Development Vision?

The 64-acre waterfront development adds thousands of new housing units to one of the world’s most expensive places, but questions remain about its future.

Coordinate or Fall Short: The New Normal

Public officials and nonprofits say teaming up and pooling resources are vital strategies for success in a climate-changed world.

Pleasant Hill Gets Sustainable Street Improvements

An intersection redesign with safer bike lanes earned a national Complete Streets award, while sparking mixed reactions from drivers.

Six Months on the Community Reporting Beat

The magazine worked with four journalists in training from community colleges, and began building a stronger network in under covered communities.

Rio Vista Residents Talk Health and Air Quality

A Sustainable Solano community meeting dug into how gas wells, traffic, and other pollution sources affect local air and public health.