The Path to a Just Transition for Benicia’s Refinery Workers

Next year, one of the three remaining oil refineries in the Bay Area will shut its doors permanently, leaving more than 400 employees out of work. And while California plans to close all its oil refineries in order to cut its emissions and ultimately prevent the worst-case climate change scenario, state and local governments have a long way to go before they can usher in a just transition for those workers.

“We’ve seen [it] happen over and over again,” says Christine Cordero, co-director of the Asian Pacific Environmental Network. “The company will just want to maximize profits. They’ll file for bankruptcy, their assets will be stranded, and then workers and communities get left holding the bag.”

The refinery, based in Benicia, is owned by Valero and processes 170,000 barrels of crude oil per day. It also contributes $11 million worth of annual property taxes to Solano County, making it the single largest taxpayer in Benicia. The Valero plant will be the second oil refinery to close in the region in recent years, two closures that are part of a much larger transition.

California is historically one of the country’s top oil producers, but the state is taking steps to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045. In the Bay Area, oil production is on track to decrease by 65% to 92% in the next 20 years. Just how this shift will impact the 18,000 people currently employed in the Bay Area’s oil refineries is a wide-open question.

Valero refinery in Benicia. Photo courtesy BlueGreen Alliance Foundation

When the Marathon Martinez Refinery closed in 2020, the company laid off over 700 employees, including 350 members of the United Steelworkers union, with minimal notice. And while some employees moved on to work in other refineries, others signed severance agreements that made it difficult to do so. One year after the layoffs, 26% of the 700 workers still had not found jobs.

In response to the Martinez closure, a group of academics, labor unions, and environmental justice groups formed a historic coalition, known as the Contra Costa Refinery Transition Partnership.

“This closure was really a wake-up call for us here in Contra Costa County,” says Josh Sonnenfeld, senior California strategist with the BlueGreen Alliance, a nonprofit that helps to bridge the gap between labor groups and environmentalists. “[We need to] advance the energy transition in a way that centers workers and communities.”

BlueGreen Alliance secured a grant from California’s Workforce Development Board, which helped fund a research project by the UC Berkeley Labor Center. The project culminated in a report that used community engagement, feedback from workers, and local government stakeholders to understand the impacts of transitioning away from fossil fuels on workers and their communities. It considered a variety of options for state policies that would facilitate a more just transition — both for companies and workers.

One of the report’s authors, Jesse Hammerling, who co-directs the Green Economy Program at the UC Berkeley Labor Center, hopes that the research will help the state avoid repeating some of the mistakes it made in 2020. “I have a lot of concerns about what will happen to the workers at Valero if it shuts down, based on the experiences of workers at Marathon Martinez, and the fact that the permanent workforce at Valero is not represented by a union,” Hammerling says.

Union oil workers demonstrate with community and labor groups during the pandemic. Photo courtesy BlueGreen Alliance Foundation

Refinery workers typically earn around $50 an hour plus benefits. The typical wage for workers without a college degree outside of the refineries is closer to $25 an hour. And without unions, they can no longer fight to improve their standards or wages through collective bargaining.

“These workers don’t have extensive and highly transferable, relevant skill sets,” Hammerling says. A report appendix highlights their potential to work in pharmaceutical manufacturing, chemical manufacturing, and water utilities. But none of those industries is likely to grow to replace oil refineries directly. “The skills themselves are there. It’s the jobs that aren’t there,” says Hammerling.

Tracy Scott is a former oil refinery worker and the president of the Bay Area’s United Steelworkers Union Local 5, which represented half of the employees at the Martinez refinery. He says that many of the workers have ended up in sectors with fewer regulations, potentially dangerous work environments, and less pay.

Meeting of a historic coalition of transition partners. Photo courtesy BlueGreen Alliance Foundation

This is where the Contra Costa Refinery Transition Partnership comes in. Labor and environmental organizations realized that it would be mutually beneficial to work together on a framework for a just transition in the refinery sector.

“We see ourselves as an integral part of that transition,” Scott says, “but, we can’t help if we aren’t asked, and that’s across the board by the city, county, state, and the corporations that are making these decisions that impact our members’ lives.”

Scott says the unions got involved because they had been given no other opportunity to have a voice. The decision to close the refinery was “a business decision that was made in a corporate setting,” he says. “Workers had no party there.” He hopes that in the future the dynamic will include more stakeholders.

Report Recommends Creating a Safety Net

The coalition’s report is centered around the core principles of securing good jobs and making polluted communities healthier, and it includes a number of specific and actionable policies. It advocates for a statewide policy requiring refineries to give two years’ notice before closing. The report also recommends creating safety net policies — financial aid, job training — for laborers who are looking for new jobs.

“There’s really a need for deliberate planning and economic development that prioritizes certain types of job growth with an attention to job quality,” says Hammerling.

In terms of building healthier communities, the report suggests converting old oil refineries into facilities for renewable energy production, rather than tearing down existing infrastructure.

And yet while shifting production to hydrogen and alternative fuels may extend operations for some refineries, it’s not clear that they’ll be any safer for workers. Most hydrogen, in particular, is still produced using fossil fuels. And the report’s authors point out that its risks to workers and the environment are yet to be fully understood. In the case of complete rebuilds, the report advocates for policies that require oil companies to bear the financial costs of remediation in the footprints of former refineries, rather than putting the cost onto municipalities and their taxpayers.

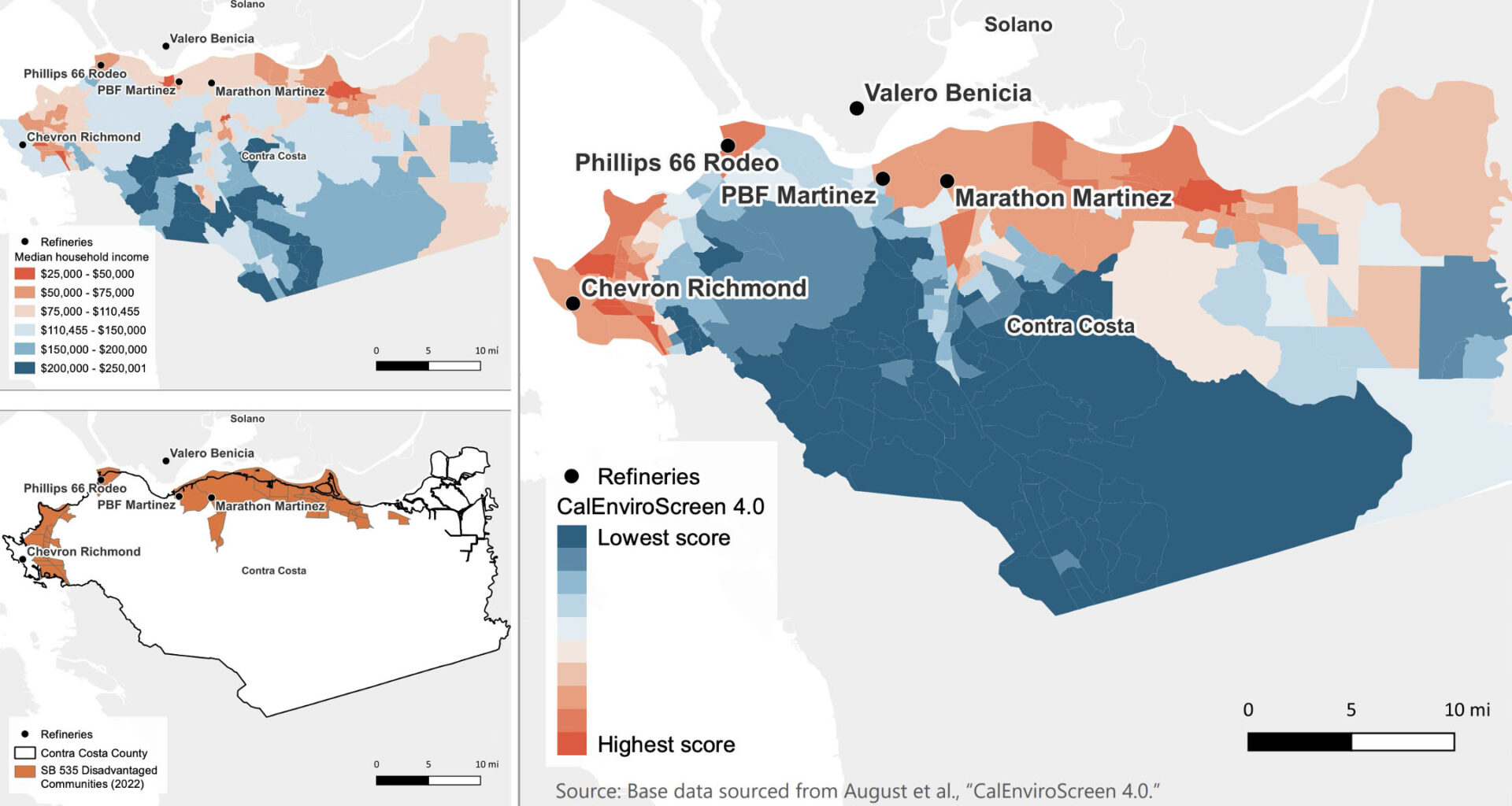

Contra Costa County stats: Median household income (top left); disadvantaged communities (bottom left); and pollution-burdened areas (right). Source: UC Berkeley Labor Center

The report says that investments into manufacturing batteries, electric vehicles, and offshore wind components could be critical to boosting the region’s economy, creating new jobs in clean energy that fits workers’ skill sets, while also tapping into sources of tax revenue that are independent of refineries.

The report also suggests that any just energy transition should be led “from the ground up,” by the communities that will be most affected.

Valero and Marathon did not respond to requests for comment, but Michael Ghielmetti, the president of Signature Development Group, says his company is working with Valero to “explore potential redevelopment of the site and plan for its future.” Signature has a track record of developing large-scale combined housing and retail spaces such as Brooklyn Basin in Oakland and Willow Village in Menlo Park.

Report cover; top 10 industries by output in Contra Costa County, in billions (2022). Source: UC Berkeley Labor Center

Doing Right by Workers

Labor groups and environmental justice organizations are often pitted against one another in discussions about the energy transition, but Contra Costa’s fledgling refinery transition partnership has helped provide a path to work together.

“We have seen how closures — whether it’s a refinery, a coal mine, a military base — don’t center the workers or communities,” says APEN’s Cordero. With planning and joint advocacy, she adds “there’s actually an opportunity to get something right, but if we leave it to the corporations and industry to determine the transition, neither the workers nor the communities are going to win out.”

When APEN started its work in a Laotian immigrant refugee community in Richmond over 30 years ago, it found many Laotian women living near refineries reported health issues in themselves and their children. Since then, research has shown that the neighborhoods closest to the refineries have disproportionately high rates of cancer and respiratory disease compared to the rest of California, and that pollution unevenly burdens low-income communities and communities of color.

And while closing refineries will have a sizable impact on the region’s tax base, it will also likely result in savings in the form of healthcare costs. According to the Labor Center report, “eliminating the emissions associated with petroleum refining would create air quality and health benefits that are estimated to be worth $70–$140 million to Contra Costa County and $280-$540 million to California annually.”

Cordero recognizes the fear workers feel as they lose their livelihoods when refineries close, but she stresses that it’s many of the same people and their families who have been deeply impacted by the pollution. “All workers are community members, and all community members are workers,” she says. “Contra Costa County is made up of people who are both of these identities.”

APEN prayer ceremony. Photo: APEN

As the Valero closure approaches, Hammerling says the state has moved in the right direction by initiating the Displaced Oil and Gas Worker Fund pilot program, which provides grants to community-based organizations, schools, and programs that assist workers in training for new jobs. The coalition also recommends that the state create a fund to support workers financially throughout the transition.

The coalition members also stress that it shouldn’t be on Contra Costa and Solano counties alone — which together are home to all the refineries in Northern California — to weather the storm. All Bay Area communities have benefited from the affordable oil produced in the two counties, and they point out that it’s an important time for the state and the Bay Area’s local governments and institutions to give back to the communities that made it possible. “External support for [communities] is going to be crucial,” says Hammerling

This story was produced with support from the Climate Equity Reporting Project at Berkeley Journalism.