Royally Flooded: Dispatches from the Highest Tides

Waves break over two-story Pacifica homes during a high tide. The previous day’s high tide was a king tide (the highest of the year), but heavy waves pushed the ocean even higher. Photo: David Chamberlin.

“Seeing how much just a foot of water can really do and how much it can flood…is kind of scary.”

In the first days of 2022, thousands of people took to the California shore to catch a live preview of sea-level rise in the coming decades.

They were not disappointed. Cars entering the freeway ramp in Mill Valley whizzed through hundreds of yards of ankle-deep seawater. Next to the San Francisco International Airport runway, baywater burbled up to the road from a storm drain. And in Pacifica on the San Mateo County coast, hundreds of hopeful crabbers on the pier ignored the waves breaking over the sidewalk and onto the road by the pier’s entrance.

This “sunny day” flooding, where the sea encroaches on dry land absent a storm or rainfall, arrived because of a king tide, a non-scientific nickname for the most extreme natural tides of the year. King tides, also called royal tides, are predictable down to the minute, and push the ocean several inches to several feet higher than it rises during the rest of the year. In recent years, king tides have inspired a movement to help people imagine life in the not-too-distant future, when these higher sea levels we now experience only a handful of days a year become commonplace.

That was why a hundred people of all ages crowded San Francisco’s Embarcadero on a grey December morning, straining to social distance in the crowd of strangers while keeping an eye on the quickly rising tide and listening to Exploratorium presenter Lori Lambertson explain the science behind king tides.

In a nutshell: Earth reaches the part of its orbit that brings it closest to the sun during the northern hemisphere’s wintertime. And in any month of the year, the highest high tide happens when the moon and sun are lined up best to tug on the sea from the same direction. Combine Earth being closer than normal to the sun with the monthly highest tide from the moon’s position, and you get a king high tide.

Lambertson broke off as the attentive crowd scrambled back. A wake had pushed the ocean fully onto the San Francisco sidewalk. A century ago, with identical winds and waves, the tide would not have breached the area; the sea level was seven inches lower back then. It is expected to rise at least that much again, and possibly more, by mid-century.

A gentle wake sloshes seawater onto the Embarcadero sidewalk in San Francisco, interrupting a tide talk by the Exploratorium’s Lori Lambertson.

Video: Michael Adamson.

Just A Foot of Water

Thirty miles south of the almost-submerged San Francisco waterfront, I joined a separate king tide event under the same clouded sky. There were a dozen of us, all huddled around Barbara Camacho of local environmental group Grassroots Ecology, listening to her outline the history of the East Palo Alto marshland (and former garbage dumping ground) that was shrinking around us by the minute as the tide flowed in. Of seven distinct king tide events organized throughout the Bay Area — bike rides, paddles, strolls, and Zoom tours — this was the only one led entirely in Spanish.

Nobody in attendance had been to Cooley Landing before, although one couple lived in the adjacent neighborhood, in a home that could already be flooded with the king tide save for the embankment. Camacho took her time getting to the topic of sea-level rise on the gentle two-hour walking tour. We stopped to touch and smell native plants her organization nurtured on the degraded soil. We ambled slowly enough by the bayside to see the seawater flowing inland through a channel like a river, rising on average more than an inch every five minutes.

The king tide made a particular impact on Miguel Ángel Reséndiz and Maricela Carillo, a couple who live in the adjacent neighborhood. “We hadn’t really paid attention, because we saw that the water rose and fell, and maybe didn’t give it as much importance,” Reséndiz explained in Spanish. “But it is important.”

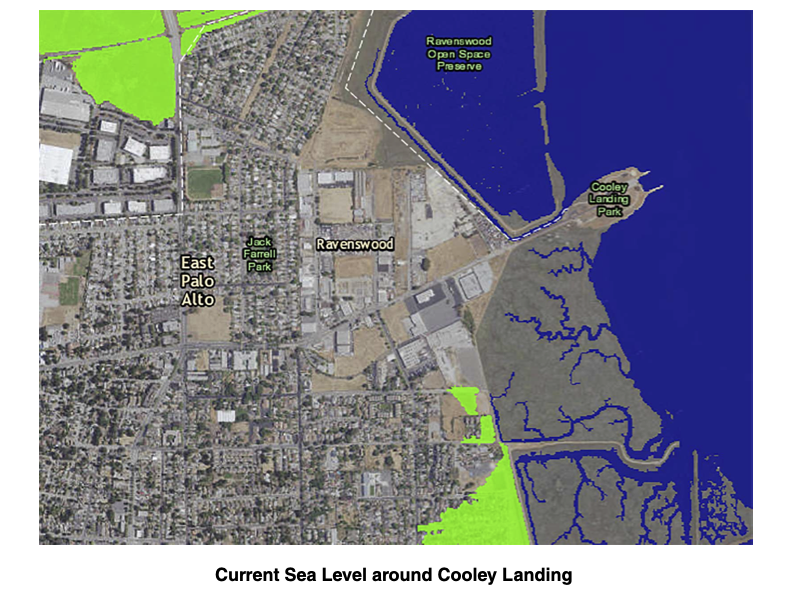

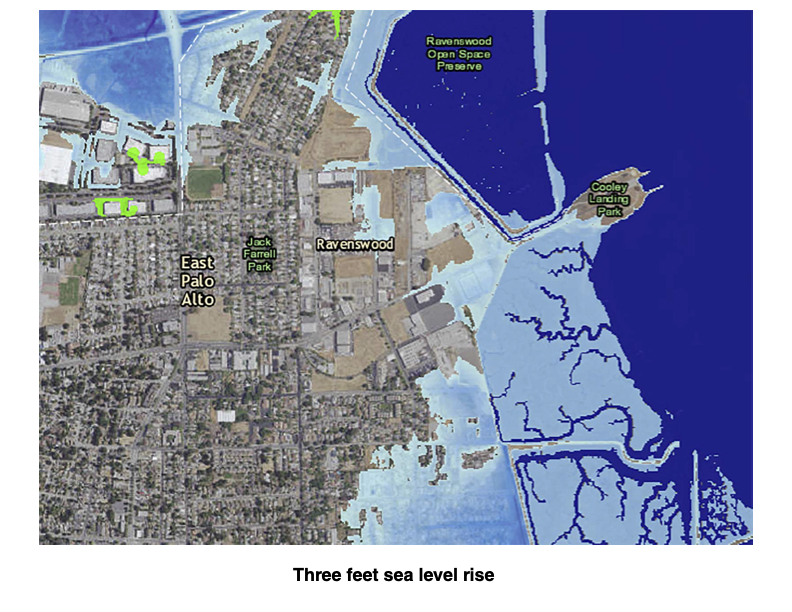

By the time we stopped on a wooden walkway above the flooded marsh, the water was poised to cover the path entirely (the staff mentioned that it did so during the previous year’s king tide). Even the children were transfixed as Camacho shared printed maps of East Palo Alto with projections for where the ocean could flood with one, three, and five feet of sea-level rise.

“It shows that not only is climate change real, but it’s going to affect people of lower income communities more,” said Alfredo Gonzalez, a Grassroots Ecology intern who was also on the East Palo Alto king tides walk. “It’s a really important time to connect the people who live in this community to the natural open spaces.” According to the Adapting to Rising Tides map, water would flood over the barrier and into the neighborhood several times a year with just two feet of sea-level rise from the baseline year 2000.

“Seeing how much just a foot of water can really do and how much it can really flood…is kind of scary,” said Brynn, a 14-year-old who joined the walk with her family. “But it’s nice knowing there are barriers.”

East Palo Alto without sea level rise (left) and with three feet of sea level rise relative to the early 2000s (right). Green represents low-lying areas that exist at or below sea level.

Source: NOAA Sea Level Rise Viewer.

Eye Of The Beholders

For some, the king tides were a spectacle, like seeing an eclipse or an exceptionally active zoo animal. Several passersby at coastal locations during the December and January king tides — and even the Exploratorium’s Lambertson — bandied about words like “exciting.” One man described seeing the extreme high as “fun.” After years of chasing the king tides up and down the coast of California, I’ll admit that I get it. There is sometimes a perverse exhilaration in photographing these natural extremes.

But when I steadied my camera within view of the SFO runway, where a thin strip of wall held the water at bay, I began to sweat. Observing those ordinary takeoffs and landings while the ocean lapped along the edge brought a tightness to my chest. Perhaps it was exciting in a sense — but definitely not fun.

Still others found the shrunken shoreline unimpressive. Several seasoned fishers on the Pacifica pier during the January king tide dismissed the unusually high tide as secondary to the size of waves breaking along the sidewalk edge. Yes, the tide rises higher now than it did 30 or 40 years ago, but if I returned in a couple days, a few said, I’d see some real action. Pacifica photographer David Chamberlin did just that, and captured sobering photos of waves clobbering oceanfront homes during a tide that was still very high, but no longer “royally” so.

King tides also remind us how complex of an issue a few extra inches of seawater really is. The water didn’t rise uniformly around the San Francisco Bay like a bathtub ring; it flowed into some near-sea-level neighborhoods while steering clear of even lower ones protected by tidal gates. It emerged in the San Leandro suburbs far from the water’s edge through storm drains and, unseen, pressed up into the thin freshwater table beneath the ground. In Mill Valley, where dramatic flooding from the king tides closed roadways, the ocean isn’t just rising to meet the cars; the land is also sinking. It all has to be considered together to prepare the region for more sea-level rise.

High Tide in Marin. #kingtides pic.twitter.com/LljOne73Gl

— Fred Sharples (@fredsharples) January 2, 2022

Snap the Shore, See the Future

Observing these changes in real time cracks open conversations we often avoid: what will we do when the ocean rises this high on 10, 20, 50 days each year? Prompting such questions is part of the goal of the California Coastal Commission’s King Tides Project, an initiative that has urged regular people to upload photos of high king tides across the state as a window into life with sea-level rise each year since 2018. Every smartphone-wielding coast dweller, in this view, has the power to frame a glimpse of a near-future everyday water level around their home.

It seems to be working. The project now rakes in thousands of photos each season, and an article headlined “Photos from the king tides show what permanent sea level rise could look like in San Francisco Bay Area by 2050” became SFGate’s most-read story the weekend after the January king tides.

But living in a daily landscape of the highest king tides is not a prophecy; it is a direct consequence of decisions made today and tomorrow, both locally and globally. Defensive actions ranging from building seawalls to restoring ecosystems that act as buffers will shape when or whether neighborhoods flood just as much as the sea level. And a King Tides Project email offered this reminder: “Sea levels are rising…but what we ultimately experience will depend on how quickly people end the burning of fossil fuels like gas, oil, and coal.”

For Carillo, seeing the high water on the Grassroots Ecology walk made a difference in her thinking about sea-level rise, and how it could affect her five-year-old daughter and their home that sits below sea level on the edge of East Palo Alto. But because the two-hour tour of the marshland had focused in part on how well the remaining wetlands can absorb excess water and shield the land behind it, she left with a modicum of hope.

“We should care for this place,” she told me solemnly in Spanish after the Cooley Landing tour, nodding at the flooded salt marsh around us. “Because if we don’t take care of this place, if we don’t conserve it, someday the ocean could flood our community.”

KneeDeep reporters Michael Adamson and Katie Rodriguez contributed to this story.