Coordinate or Fall Short: The New Normal

Belle Haven and East Palo Alto residents hear from the Bay Area Air District about air quality, and distribute more than 100 air purifiers. Photo: CRC

Bay Area jurisdictions are coming together to merge their hazard management and climate adaptation efforts as they see significant overlap in the types of risks they must address — from fires and drought to dam failures and flooding that impact their shared roadways, powerlines, streams, and more. This type of coordination is not new, and few municipalities have the bandwidth to do it, but working together can help planners and managers pool money and other resources to complete projects.

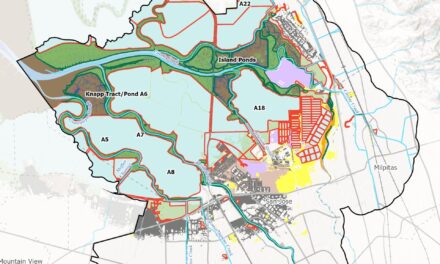

The plight of five mobile home parks in Redwood City offers an example. After more than a decade of delays in efforts to prevent persistent flooding, it took several jurisdictions coming together to fund a $10 million floodwater diversion project in 2022, which included new tide gates on the Bayfront Canal and better drainage in the Atherton Channel.

OneShoreline helped establish this collaboration between Redwood City, Menlo Park, Atherton, and San Mateo County. This special district, created in 2020, works across jurisdictional boundaries to leverage resources to mitigate the impacts of sea level rise, flooding, and coastal erosion.

During storms since 2022, the resulting improvements reduced flooding in the mobile home parks by diverting runoff into nearby wetlands.

“It was a small example … of how one jurisdiction can’t own a project that crosses into other jurisdictions,” says OneShoreline CEO Len Materman. “Atherton doesn’t flood as a result of the canal that was the focus of the project, but they [Atherton] understood that they provide the water that contributes to the flooding. … It’s not about refereeing an argument. It’s really just about what approach creates the best opportunity to move resilience work forward, and a big part of that is funding.”

In another example, when major winter storms clogged creeks with debris in late 2022 and early 2023, OneShoreline secured environmental permits for the clean up of flood-prone creeks in five cities and county areas, rather than have each jurisdiction undertake the work on its own.

Other Recent Posts

Agroecology Commons Weathers a Weird Winter and Political Storms

A year after our first Agroecology Commons visit, the El Sobrante farm has a new greenhouse foundation, thriving farmer training program, and some unexpected wildlife.

Finding Community at the Bay Area Climate Literacy Exchange

A third of our food supply goes to waste, and Bay Area students are learning how to fix it one school cafeteria at a time.

Easy Spring Vegetables for Small Gardens

Snap peas and Tokyo turnips are hardy, cool-season vegetables well-suited to Bay Area gardens. Here’s how to grow and cook them.

At Canticle Farm, Food and Community Are Prayer for a Better World

On a residential street in East Oakland’s Fruitvale neighborhood, a front yard becomes a food distribution network every Friday.

What Do Teens Think is Healthy Food?

Student reporting fellow Sachi Bansal asks three high school seniors in Fairfield about how they define healthy food, and what they think of the new food pyramid.

En Canticle Farm, la comida y la comunidad son las oraciones para un mundo mejor

Canticle Farm está reinventando el concepto de vecindario a través de la tierra compartida, la comida gratuita y la acogida radical.

En la granja agroecológica Agroecology Commons, las nutrias han vuelto

Un año tras nuestra primera visita a Agroecology Commons, la granja en El Sobrante tiene una nueva base para un invernadero, un próspero programa de entrenamiento para agricultores y una fauna inesperada.

Tide gate and trash capture device on the Bayfront Canal near Redwood City. Photo: OneShoreline

Such steps toward coordination with neighboring landowners and municipalities are increasingly called for as the region grapples with a variety of environmental, health, and safety challenges, all made worse by extreme weather and climate change.

Larger agencies are also trying to move the needle. In 2023, the Bay Area Regional Collaborative identified gaps and challenges in the region’s approach to climate adaptation. A year later, the group, made up of agencies like the Bay Area Air District and Metropolitan Transportation Commission, prioritized sea level rise. BARC would eventually like to put together a regional multi-hazard adaptation plan, says Program Coordinator Josh Bradt.

Further efforts to coordinate across jurisdictions include the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s work with the Ocean Protection Council and Coastal Quest to secure more than $20 million in grants to fund planning for mandatory sub-regional shoreline adaptation plans, says Rylan Gervase, BCDC’s director of legislative & external affairs. Solano County, Richmond, Fairfield, and other cities have initiated plans with help from BCDC.

“The sea doesn’t really care where a county ends and where another begins,” Gervase says. “The more collaboration that the local governments put into this to make sure that their plans are aligning … with their neighboring jurisdictions is going to make … these plans more likely to be successful.”

Bradt says the last decade has seen more “awareness that everybody is financially constrained,” and that the “more mutual support, the further the dollars go.”

Elevated highway intersection in Marin where king tides show future flooding. Photo: Caltrans

He pointed to a long-term sea level rise adaptation study along Interstate Highway 101 in Marin County, bolstered by a partnership between Caltrans, the Transportation Authority of Marin, the county board of supervisors, and Shore Up Marin City.

Because of Marin’s geography, Highway 101 functions as its primary intercounty transportation corridor, and in many locations, it is the only continuous north-south route connecting communities, jobs, hospitals, schools, and emergency services, Stephanie Moulton-Peters, a Marin County supervisor, writes in an email: “The early January storms illustrated how quickly access through the county can be cut off when 101 is compromised.”

And over in San Mateo County, a coalition of cities and towns is working in tandem, along with consultants like PlaceWorks, to draft state-mandated safety elements. The plans identify natural and human-caused hazards that could affect residents and businesses.

“There was a shared need for data gathering, risk evaluation and cross jurisdiction approach to natural disasters, hence collaborating was prudent,” says San Mateo County’s Bharat Singh.

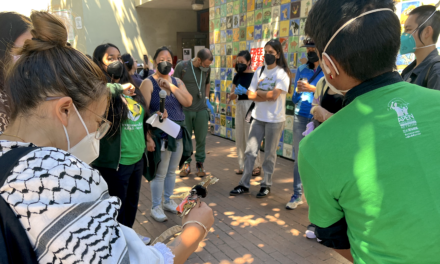

With the federal government clawing back grants for climate projects, it appears it’s now even more important for organizations to diversify their funding sources. In March 2025, for example, Palo Alto nonprofit Climate Resilient Communities scrambled to make up for a $500,000 EPA grant that funded air quality monitoring for families with asthma in East Palo Alto. The Grove Foundation, Sobrato Philanthropies, and Magic Cabinet stepped in to help, according to Cade Cannedy, CRC’s senior director of programs and communications.

Climate Resilient Communities hands out air filters in East Palo Alto. Photo: CRC

But organizations like OneShoreline say they will need to rely more on local and state funding going forward. “We never thought the federal government was going to come in and save us from sea level rise,” says Materman.

“Coordination is becoming a necessary mantra,” says BARC’s Bradt.