Marshes Could Save Bay Area Half a Billion Dollars in Floods

What, precisely, is the value of habitat restoration? While answers tend to aim for pristine nature and thriving wildlife, one approach — recently published in the journal Nature — has assigned salt marsh restoration projects a dollar value in terms of human assets protected from climate change driven flooding. This novel approach uses the same models engineers use to evaluate the value of “gray” solutions such as levees and seawalls.

“You can really compare apples to apples when you put these green climate adaptation solutions on the same playing field as gray infrastructure,” says Rae Taylor-Burns, a postdoctoral fellow with UC Santa Cruz’s Center for Coastal Climate Resilience and lead author of the study.

Given that sea level is expected to rise by 1.6 to 7.2 feet (0.5 to 2.2 meters) by 2100, such value assessments are going to become increasingly relevant to the large population living and working near the low-lying shorelines of the San Francisco Bay Area. The region has already seen significant damage from floods when combined with high tides and storm surges. Statewide, if sea level rise reaches more than seven feet (2 meters), 675,000 people and $250 billion in property will be exposed to flood risk in the event of a 100-year storm.

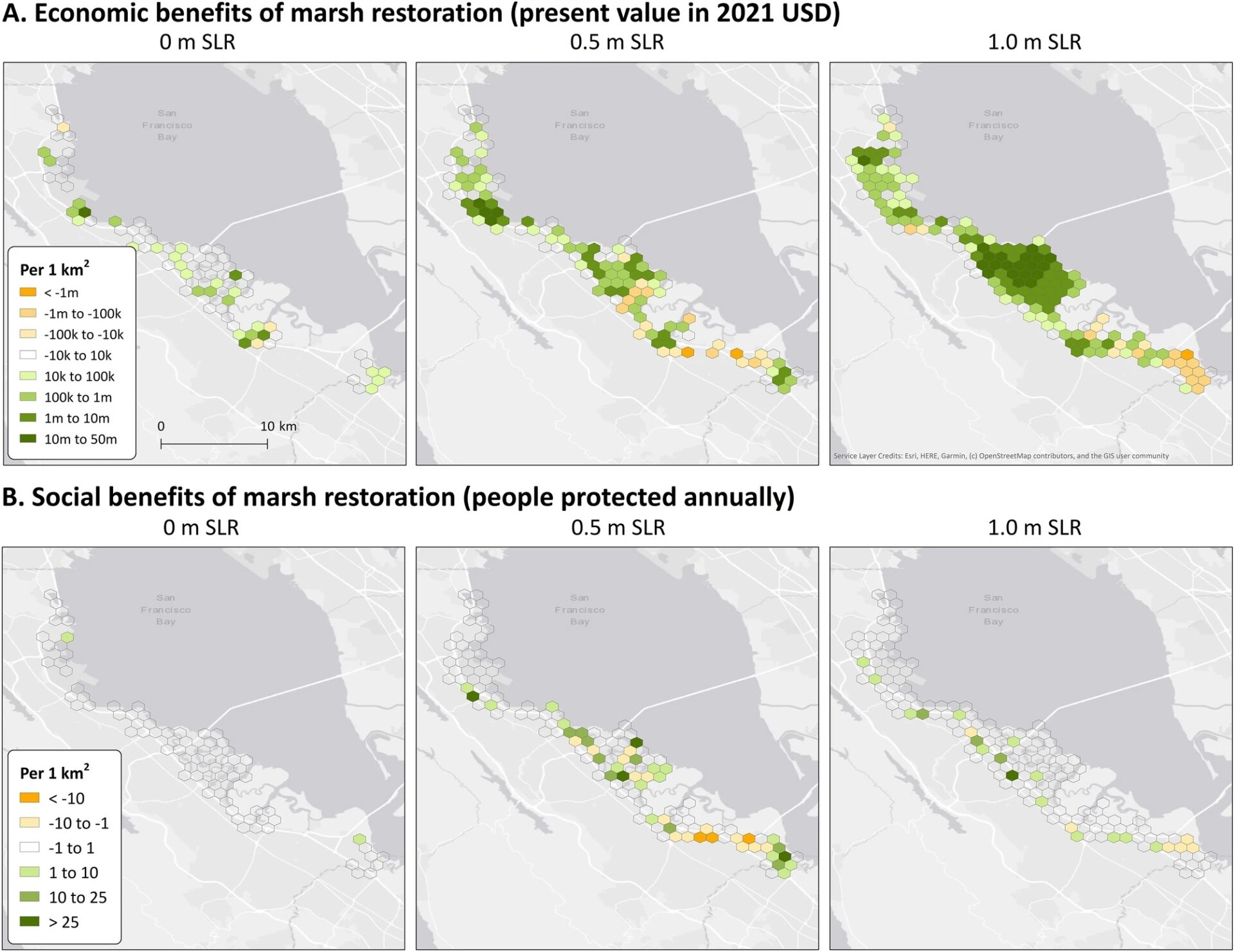

Map of (A) economic and (B) social benefits from flood reduction of marsh restoration with sea level rise. Green colors represent positive present value and people protected and orange colors show negative present value and increased risk. Source: UC Santa Cruz

Other Recent Posts

Reforming Rules to Speed Adaptation

Bay Conservation and Development Commission to vote early this year on amendments designed to expedite approval of climate projects.

Warner Chabot Shifts Gears

After 11 years at the helm of the Bay Area’s leading science institute, its leader moves back into the zone of policy influence.

Is Brooklyn Basin Emblematic of Regional Development Vision?

The 64-acre waterfront development adds thousands of new housing units to one of the world’s most expensive places, but questions remain about its future.

Coordinate or Fall Short: The New Normal

Public officials and nonprofits say teaming up and pooling resources are vital strategies for success in a climate-changed world.

Pleasant Hill Gets Sustainable Street Improvements

An intersection redesign with safer bike lanes earned a national Complete Streets award, while sparking mixed reactions from drivers.

Six Months on the Community Reporting Beat

The magazine worked with four journalists in training from community colleges, and began building a stronger network in under covered communities.

Rio Vista Residents Talk Health and Air Quality

A Sustainable Solano community meeting dug into how gas wells, traffic, and other pollution sources affect local air and public health.

New Year Immerses Concord Residents in Flood Preparations

In Concord, winter rains and flood risks are pushed residents to prepare with sandbags, shifted commutes, and creek monitoring.

What You Need to Know About Artificial Turf

As the World Cup comes to the Bay Area, artificial turf is facing renewed scrutiny. Is it safe for players and the environment?

Threatened by Trump’s Policies, GreenLatinos Refuses to Back Down

National nonprofit GreenLatinos is advancing environmental equity and climate action amid immigration enforcement and policy rollbacks.

The Bay Area filled or destroyed the majority of its 190,000 acres of historic tidal wetlands — natural buffers against waves, storms and sea level rise — over the last 200 years, with only 40,000 acres remaining by the 1990s. In recent decades, the region’s marsh extent has crept back up to 80,000 acres thanks to modern restoration projects (with 24,000 acres of additional restoration projects in the pipeline). Much of the region’s highly urbanized shore depends on complex gray infrastructure like levees, dikes, seawalls, and seawater pumping for flood protection.

However, according to Taylor-Burns, the current value of marsh restoration within her study area of San Mateo County is $21 million. Under current conditions, nearly half of the people benefiting from flood reduction due to restoration live in socially vulnerable census areas, the UC Santa Cruz paper stated. However that percentage would decrease as sea levels rise and the vulnerable are displaced — as the low-lying areas would be inundated, and the floodplain would expand into higher elevations and more affluent census blocks.

As sea levels rise, so do the financial benefits of marsh restoration: to over $100 million under conservative estimates of 1.6 feet (0.5 m) of sea level rise, and up to roughly $500 million given moderate 3.3 feet (1 m). Financial benefits are calculated by Taylor-Burns’ team using the input of a variety of local planners and government stakeholders. They utilized hydrodynamic models to determine flood depths and extents, and then used census and building stock data to determine the impact of the flood in dollar amounts and in terms of people impacted. Countywide, the flood reduction benefits of salt marsh restoration would increase by a factor of 23 given 1.0 m of sea level rise.

Taylor-Burns says the evaluation of benefits is likely conservative, because it did not consider co-benefits to the restoration — such as positive impacts on recreation or water quality, the paper notes. Likewise, it did not consider benefits to endangered species.

“If you think about quality habitat for animals, that is likely to be large expanses where they can be separate from the built environment,” Taylor-Burns says. “The restoration that could benefit endangered species might not be in the same place as those that would provide the greatest flood risk reduction.”

South Bay salt pond restoration project site near shoreline development. Photo: David Hasling

Even in terms of dollars, some restoration projects would deliver even higher benefits, based on what infrastructure is nearby — such as the narrow fringe of restored marsh near the San Francisco Airport which provides a present value of $900,000 per hectare.

“Small restorations that are adjacent to, say, a Google campus or densely developed suburbia would offer more risk reduction benefits than larger island restorations,” Taylor-Burns says. “But in a nutshell, the findings show that marsh restoration can play a role in reducing flood risk in the bay pretty substantially.”