How Rivers in the Sky Travel Across the Ocean

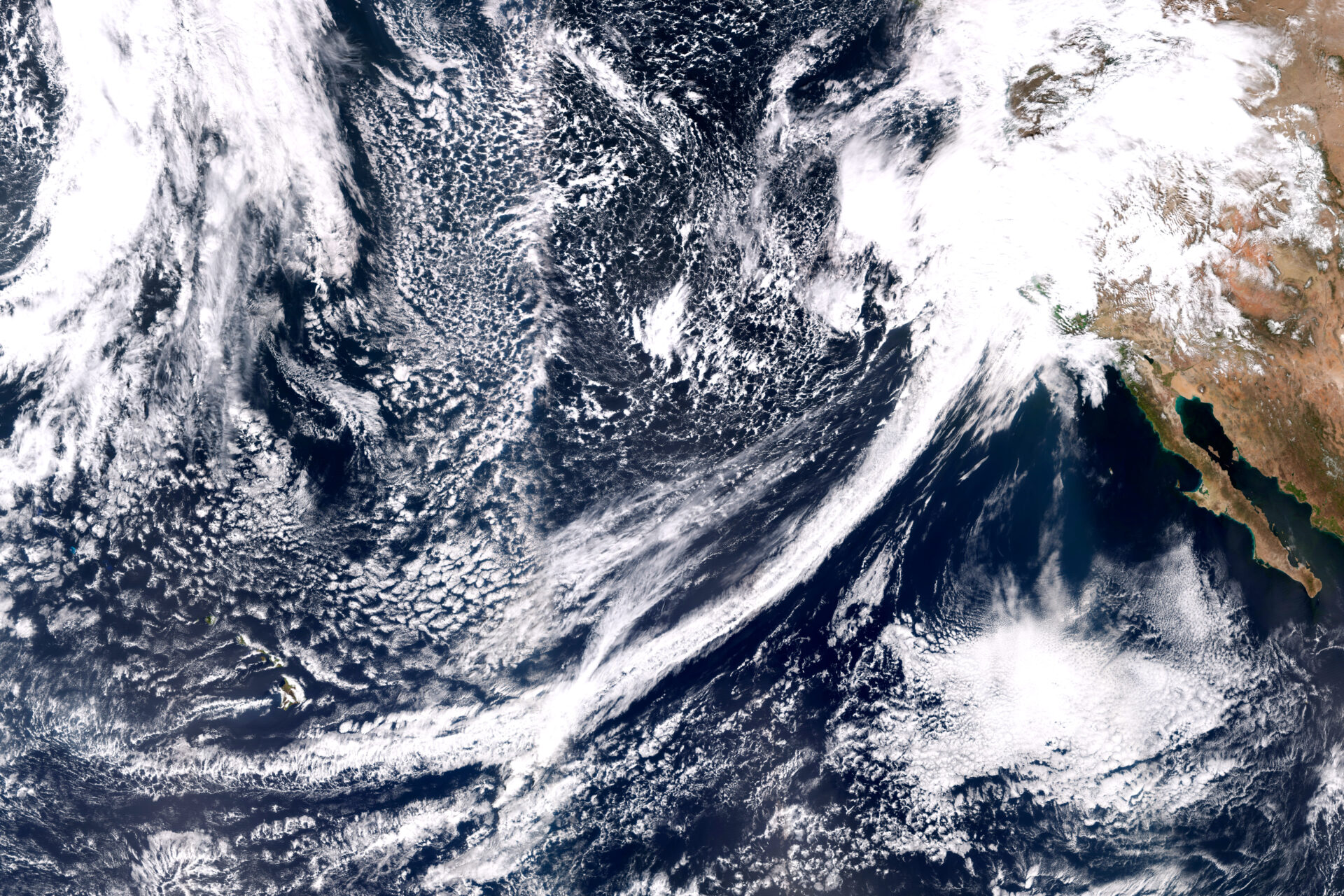

Winter in California is a time of promise and peril. We’re desperate for rain, only not too much please. Our fate swings from drought to floods, depending largely on whether or not we get rainstorms called atmospheric rivers. These ribbons of extraordinarily wet air shoot across the Pacific Ocean, dropping the moisture they carry upon landfall.

The Bay Area’s latest “wet” season began with the bang of a record-breaking atmospheric river in late October but then fizzled out. These storms have been so scarce in the last few months that the state is facing a third year of deepening drought.

Atmospheric rivers typically begin over oceans in the tropics, where it’s so warm that water evaporates readily, filling the air with moisture. Then all it takes to start an atmospheric river is a storm called an extratropical cyclone, which spins over the ocean and sweeps up the wet air.

“Atmospheric rivers are seeded by convection storms that move water vapor from the surface to a couple of kilometers high,” says Alan Rhoades, a hydroclimate scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Atmospheric rivers that form over the Pacific Ocean are then launched and propelled toward the West Coast by strong winds. “You need a driver like a low-level jet stream,” says Zhenhai Zhang, an atmospheric scientist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “The jet carries the moisture and moves fast in a narrow corridor.”

This airborne stream of water vapor then traverses a series of low and high pressure regions that are strung across the ocean. These regions set the path of the atmospheric river, which can be so long that it extends halfway across the Pacific. “A low grabs the water vapor and moves it northward, and a high then steers it toward the West Coast,” Rhoades says.

He likens this process to a conveyor belt, where the low and high pressure systems are like rollers that direct the atmospheric river. Another way to look at this process is that the low and high pressure areas are like the pegs of an enormous pinball machine, guiding and redirecting the flow of the atmospheric river and so shaping its trajectory toward land.

Other Recent Posts

Assistant Editor Job Announcement

Part time freelance job opening with Bay Area climate resilience magazine.

Training 18 New Community Leaders in a Resilience Hot Spot

A June 7 event minted 18 new community leaders now better-equipped to care for Suisun City and Fairfield through pollution, heat, smoke, and high water.

Mayor Pushes Suisun City To Do Better

Mayor Alma Hernandez has devoted herself to preparing her community for a warming world.

The Path to a Just Transition for Benicia’s Refinery Workers

As Valero prepares to shutter its Benicia oil refinery, 400 jobs hang in the balance. Can California ensure a just transition for fossil fuel workers?

Ecologist Finds Art in Restoring Levees

In Sacramento, an artist-ecologist brings California’s native species to life – through art, and through fish-friendly levee restoration.

New Metrics on Hybrid Gray-Green Levees

UC Santa Cruz research project investigates how horizontal “living levees” can cut flood risk.

Community Editor Job Announcement

Part time freelance job opening with Bay Area climate resilience magazine.

Being Bike-Friendly is Gateway to Climate Advocacy

Four Bay Area cyclists push for better city infrastructure.

Can Colgan Creek Do It All? Santa Rosa Reimagines Flood Control

A restoration project blends old-school flood control with modern green infrastructure. Is this how California can manage runoff from future megastorms?

San Francisco Youth Explore Flood Risk on Home Turf

At the Shoreline Leadership Academy, high school students learn about sea level rise through hands-on tours and community projects.

Instruments on this Sonoma County ridge measure precipitation, temperature, humidity, winds, barometric pressure, and more. Scientists use the data to connect the hydrology of the Russian River watershed to atmospheric river forecasts. Photo: Scripps, UCSD.

That trajectory is hard to predict, however. “Atmospheric rivers are often called whips or hoses because their path can shift in different directions,” Rhoades says. This is partly because these storms depend on wind, which changes from hour to hour. Atmospheric river speeds are difficult to pin down but may vary from 20 to 100 kilometers per hour.

And while the path can look fairly smooth at a global scale, up close it’s a different story. “At a small scale, it’s challenging to predict the exact path of an atmospheric river,” Zhang says, adding that an atmospheric river’s size, shape and intensity are also in flux.

Taken together, all this variability makes it hard to know exactly how strong an atmospheric river will be and exactly where it will make landfall. Another complication is that atmospheric rivers can be just a few hundred kilometers across. This is very close to the uncertainty in predictions of where they will hit, which can be off by a couple hundred kilometers. “That’s the difference between landfall in Los Angeles or in San Diego,” Zhang notes.