How Cities Can Make AI Infrastructure Green

Art: Afsoon Razavi

Lauren Weston says concerns about artificial intelligence come up at half the staff meetings at Acterra, the Palo Alto-based environmental nonprofit she runs.

The organization advocates for responsible water and energy consumption by the local data centers that power AI platforms like ChatGPT, which are dominating conversations and investments in both the Bay Area and the entire tech world at large right now.

But influencing companies with virtually unlimited resources — OpenAI, Google, Amazon, and Microsoft to name a few — can feel like an insurmountable task.

“At some point, it just feels like we’ll never have a say in what happens because we just don’t have the resources, we don’t have the bodies, we don’t have the elected officials in the same way,” says Weston. “It can feel really like an uphill battle.”

Acterra, which more often champions electrification and trains high school and college students on climate action, is trying to get all levels of government to better regulate and monitor the AI industry.

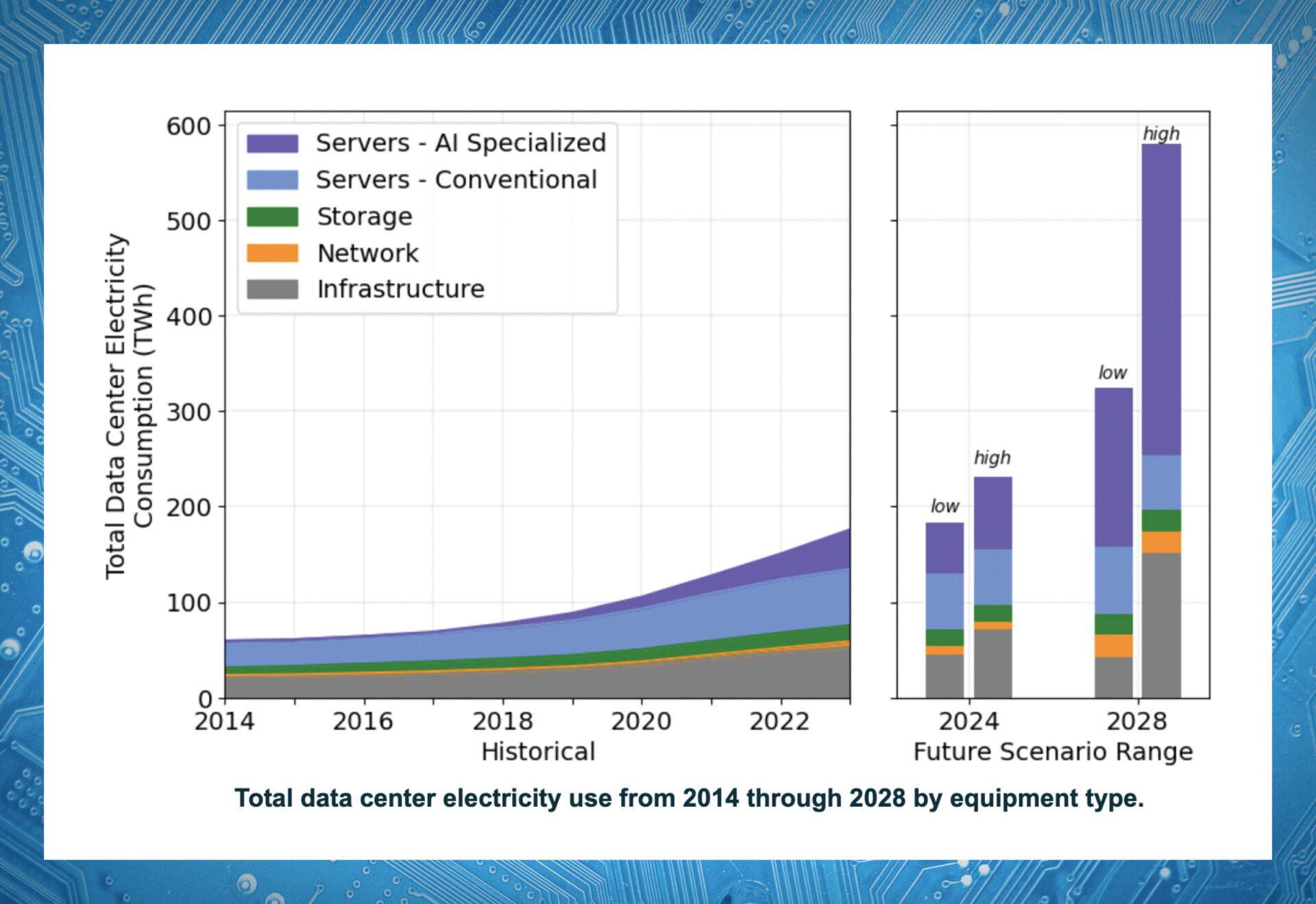

Data centers have been around for a long time, running servers that store internet data and generally keep websites up and running. These early generations of servers use a relatively low amount of electricity and water, while the so-called “accelerated” data center servers that power AI require 10 to 20 times as much energy, according to Eric Masanet, a UC Santa Barbara professor who co-authored the 2024 U.S. Data Center Energy Usage Report.

The AI chatbots that people commonly use nowadays run on large language models that essentially use the entire history of the internet to answer questions. That amounts to a lot more power consumption and a lot more heat emitted by servers — and more water for cooling.

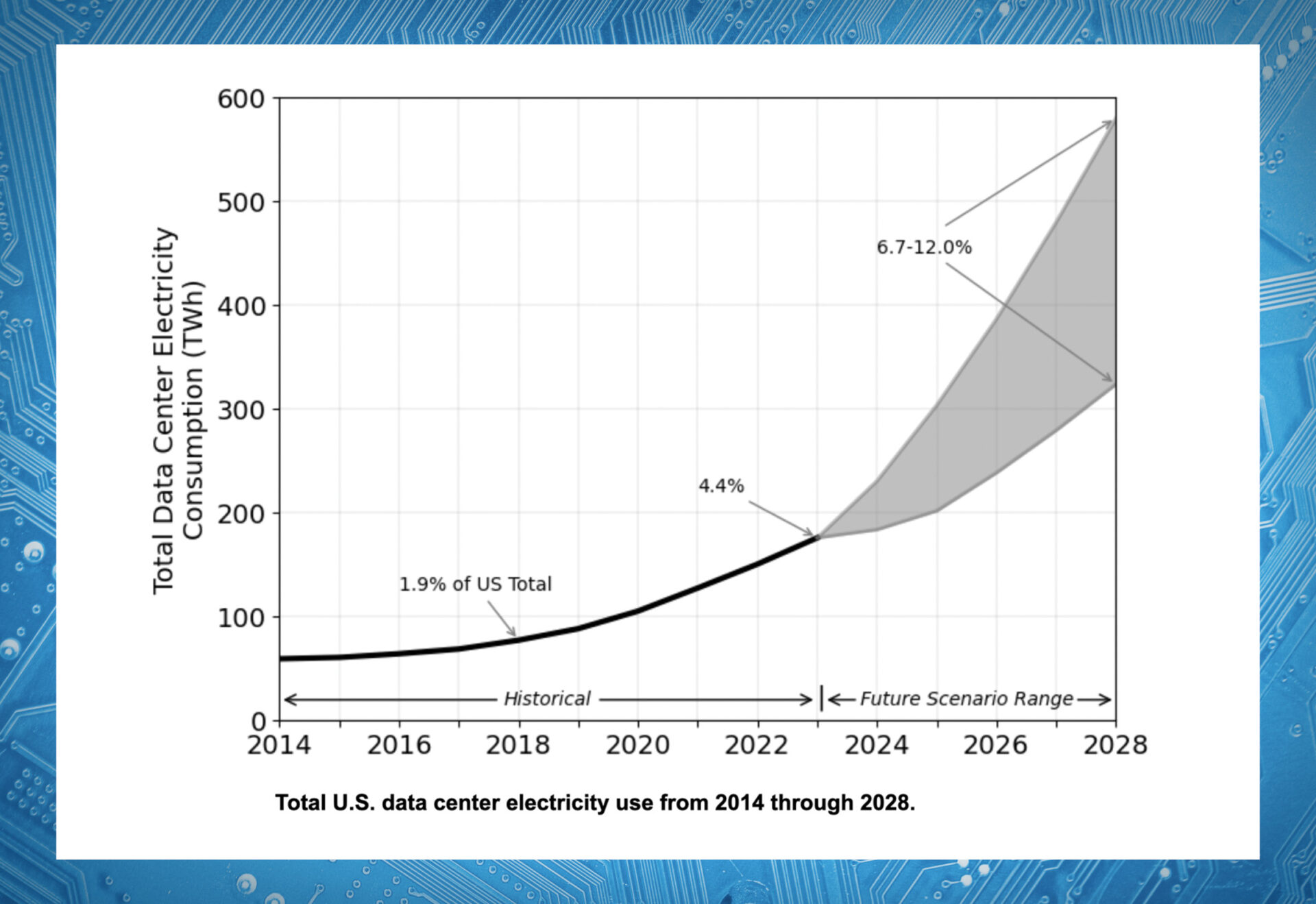

As a result, the percentage of total energy consumed by data centers is skyrocketing. The study found that data centers accounted for 4.4% of total U.S. electricity in 2023 and projects that number to rise to somewhere between 6.7% and 12% by 2028.

About a decade ago, the study finds, the emergence of accelerated servers set off “a new trend that led to the approximate tripling of energy use from 2014 to 2023” by U.S. data centers. And their resource consumption doesn’t stop with energy.

“There could be many environmental [impacts from] data centers, including local land use, water use, local air pollutant emissions from backup generators or electric power stations, clearly carbon emissions, e-waste,” Masanet says.

But such impacts can be managed. According to researchers, climate advocates, and elected officials interviewed by KneeDeep, local governments can establish policies requiring carbon neutrality and recycled water use for any data centers to get city approval. They can also make sure data center companies cover the cost of expanding the local power grid if that’s necessary for their operations, so the average consumer’s utility bill doesn’t go up.

Ultimately, when it comes to the question of just how bad AI could be for the environment, “the answer is almost always ‘it depends,'” Masanet says.

Santa Clara Insists

The City of Santa Clara is the Bay Area’s data center capital. Of the 110+ data centers in the region, more than 50 are in this well-to-do city of 127,000, where more than 65% of the residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher, and the median household income is $173,000.

Suds Jain, a member of the Santa Clara City Council since 2020, says tech companies build data centers there because power is cheaper. Santa Clara buildings get their electricity from Silicon Valley Power, which costs 60% less than Pacific Gas & Electric, according to Jain, who retired from a career in designing chips in 2008 to pursue climate advocacy.

Unlike PG&E, which is an investor-owned utility making money for shareholders, Silicon Valley Power is a nonprofit owned and operated by the City of Santa Clara, which allows it to put more of its revenue back into maintaining and improving the electrical grid. All residential power and nearly half the non-residential power provided by SVP is carbon free (mostly from wind and solar energy).

Within these few blocks just west of the San José Airport, 20 data centers support artificial intelligence. Some are cooled with recycled water from local sources. Map: Google Earth

Janine De la Vega, a spokesperson for Silicon Valley Power, says data centers already account for about 60% of the city’s total electricity sales.

Councilmember Jain thinks that’s a good thing because of the policies the city has put in place to regulate the industry. Plus, he says tech companies like building data centers in Santa Clara not only because energy is so much cheaper, but also because their engineers live nearby and can easily repair them if necessary. And as a bonus, the city charges a 5% utility tax on all electricity.

“The data centers are now providing $41 million in revenue to the City of Santa Clara from sales taxes, utility taxes, property taxes,” Jain says. “It’s 14% of our general fund, so it’s a huge asset.”

On the climate resilience front, Santa Clara requires new data centers to be carbon neutral, either by drawing from local renewable energy sources or by purchasing carbon offsets. And the city also mandates data centers to use only recycled water for cooling purposes, or at least to be “recycled water ready” if their location is not yet covered by recycled water produced from the San José-Santa Clara Regional Wastewater Facility.

According to Jonathan Koomey, a co-author of the data center study, “There’s nothing bad about using recycled water for cooling. It has zero direct impact on local potable water, surface water, or aquifer supplies.”

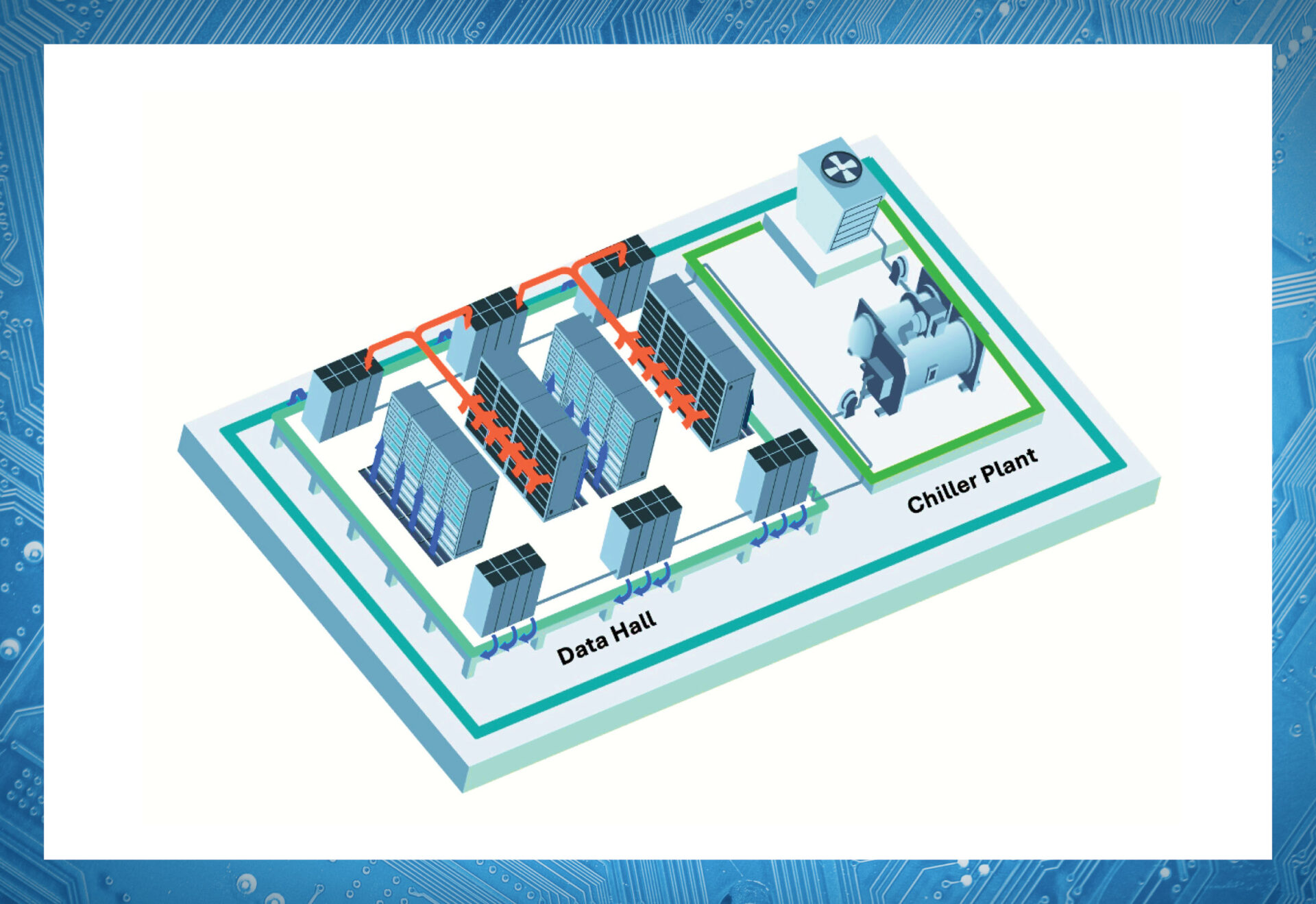

With California’s water supply so limited, what kind of water and how much of it is being used by data centers can be a sticking point. Jain is trying to pass an ordinance requiring data centers to use air chillers instead of evaporative cooling (which requires water) whenever possible, with evaporative cooling using recycled water as a backup when a server overheats. He says that when a data center uses air cooling as much as possible, it only needs about 20 families’ worth of water per year for cooling, and “that seemed to be pretty acceptable to me.”

But others say it’s not quite that simple. Koomey warns that air chillers require more energy than evaporative cooling with recycled water directly, so he prefers the latter. Santa Clara is also in the unique position of having access to recycled water from a large, state-of-the-art facility that treats 110 million gallons of wastewater per day. That option doesn’t yet exist in most other parts of the Bay or California.

Art: Afsoon Razavi

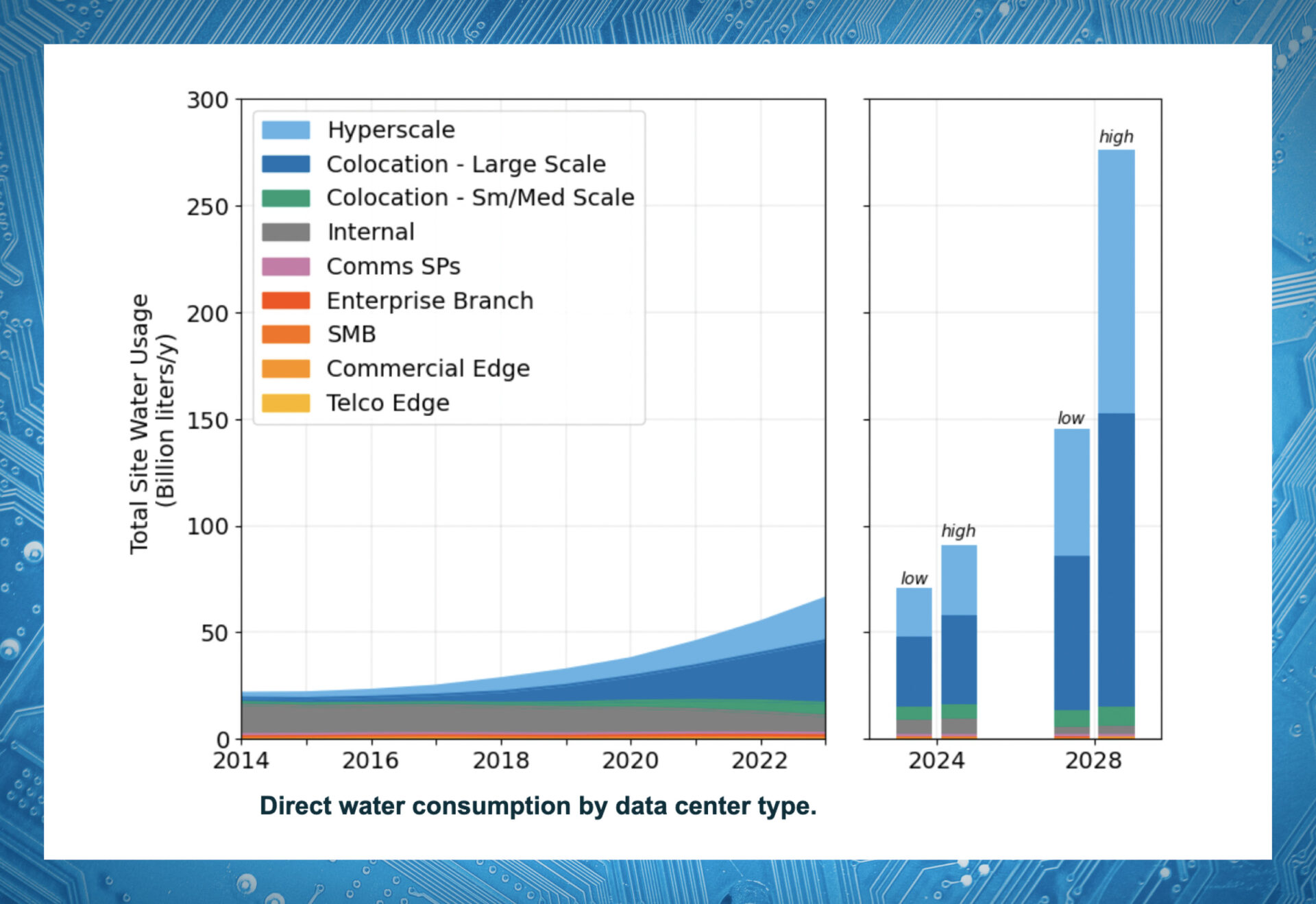

Whatever way you look at it, data centers fueling the AI boom could mean “huge additional water demand,” according to Ben Glickstein, the director of communications for the national nonprofit WateReuse Association. His organization is lobbying lawmakers in D.C. to pass a tax credit for companies that use recycled water at industrial facilities.

“On the positive side, WateReuse Association is getting a lot of proactive engagement from a lot of these big data center companies,” he says, “and we’re hopeful that water recycling is a really transformative piece of the solution that will allow the economic benefits and technological benefits of these data centers to go forward without outcompeting communities for their own water.”

Holding Big Tech’s Feet to the Fire

Despite his positive outlook for Santa Clara, Jain is still clear-eyed about the reality facing the rest of the state and the country.

“There’s a data center bubble right now,” he says, referring to the $400 billion of investment in data centers nationwide. “If it pops, a lot of cities are going to be really stranded because they didn’t charge load development fees.”

Jain is referring to city policies that force companies to fund expanded energy consumption. He worries that data centers under construction could be abandoned like old oil wells, without anyone picking up the costs borne by the cities left to deal with them. That’s why he’s urging other jurisdictions to make sure any contracts they sign to develop AI infrastructure put the funding burden on the developer.

Data centers alternate hot and cool aisles, running cold air pumped from the chiller plant through the servers. Diagram: Siemens

But there are other reasons to be hopeful. Both Jain and Weston point out a San José development approved this year, where two residential buildings will use the heat burned off by two neighboring data centers to power heat pumps and boilers.

Data centers may also be able to alleviate rolling power shutoffs during heat waves by temporarily employing their diesel backup generators for a few hours. That actually happened in 2023, Jain says, but not in the last two years. For his part, though, Masanet says all data centers should be making investments in renewable energy, whether onsite, in local grids, or through virtual power arrangements.

“It is important that people not fall for the false sense of urgency promoted by some in the data center industry,” Koomey adds. “There’s no urgency requiring us to abandon climate commitments and ignore other environmental regulations. The data center industry is very profitable, and in my view should be required to power all data centers with zero emissions power.”

Photo: Tudi Crequer, Reporterre, courtesy Climate Generation

Small Voices, Big Concerns

Acterra’s Weston remembers being interviewed by a student for a story in their high school paper about the climate impacts of AI.

“This is worrying youth, and they’re going to be the ones having to deal with this as adults. As kids become more aware of the environmental impact of the decisions of themselves and their families … they’re getting involved in the conversation, and I think their voice is really, really critical,” she says.

As for the tech companies building data centers, “they talk a big game” about committing to sustainability, Weston notes, but “we need to actually make sure they follow through.”