Rising Waters Bring New Toxics Threat to Hunters Point

“The Navy previously felt stifled by an acrimonious relationship with the community, so they went through a period of not doing a whole lot of community outreach, but they’re now much more engaged and receptive.”

“Caution. No trespassing,” reads a sign lashed to the chain link fence separating Parcel E-2 of San Francisco’s Hunters Point Naval Shipyard from the surrounding residential neighborhood. At that spot during last year’s storms, Shirletha Boxx-Holmes watched the shipyard flood.

“Mother nature did not read the signs,” says Boxx-Holmes, a Bayview native and community organizer with Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice. She watched soil from the shipyard run into neighborhood streets with the floodwater. Her stomach sank.

The 638-acre shipyard, the site of Navy radiation experiments and ship decontamination in the 1940s, is a federal Superfund site contaminated with radioactive waste and a litany of other toxic substances, including arsenic and lead. The Navy, which is overseeing cleanup, has capped much of the toxic area with asphalt or soil to contain the contamination and protect people and the San Francisco Bay ecosystem. However, climate change-fuelled sea level and groundwater rise are expected to open up new pathways for the contamination to spread, which may demand new solutions.

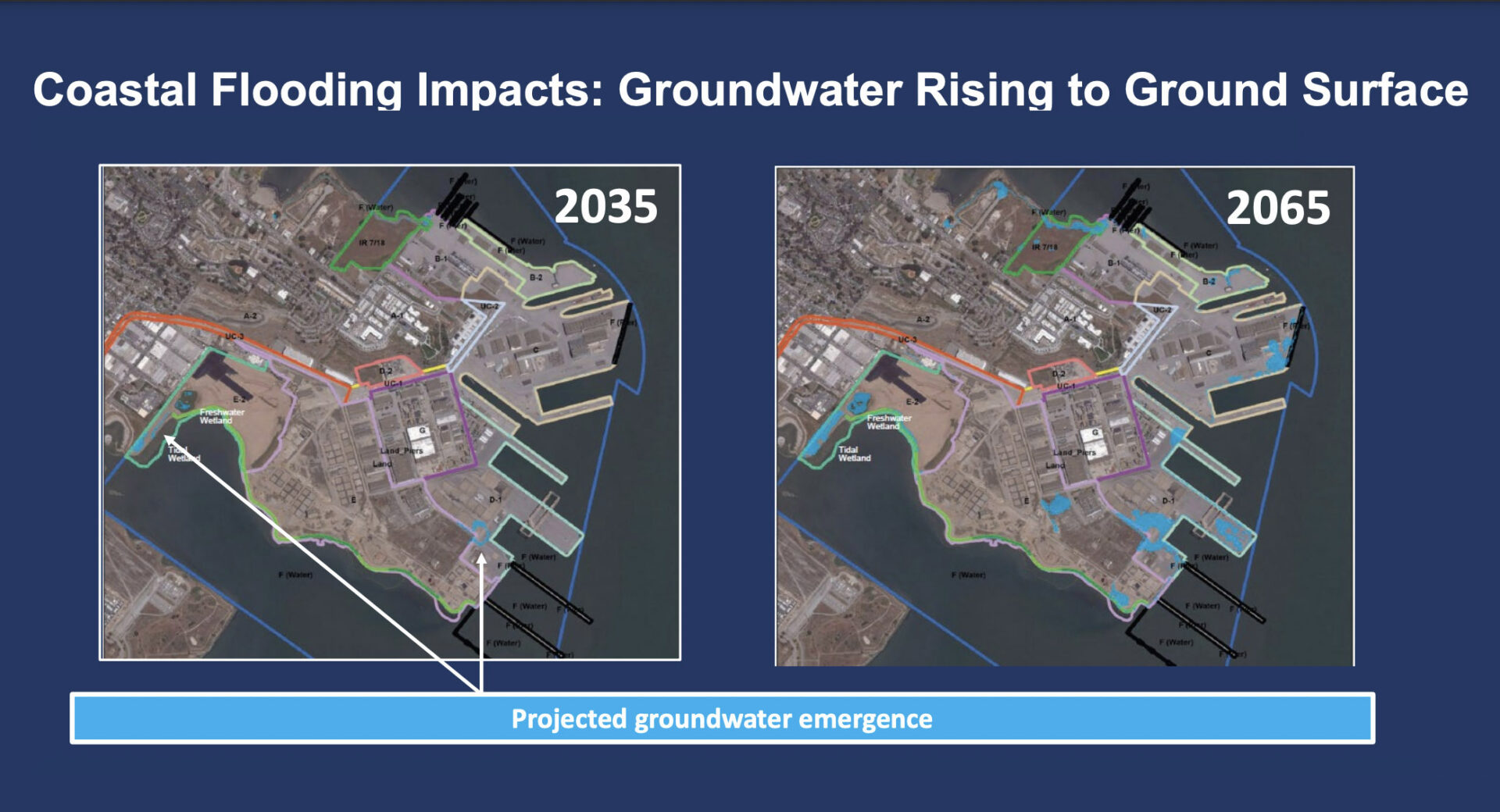

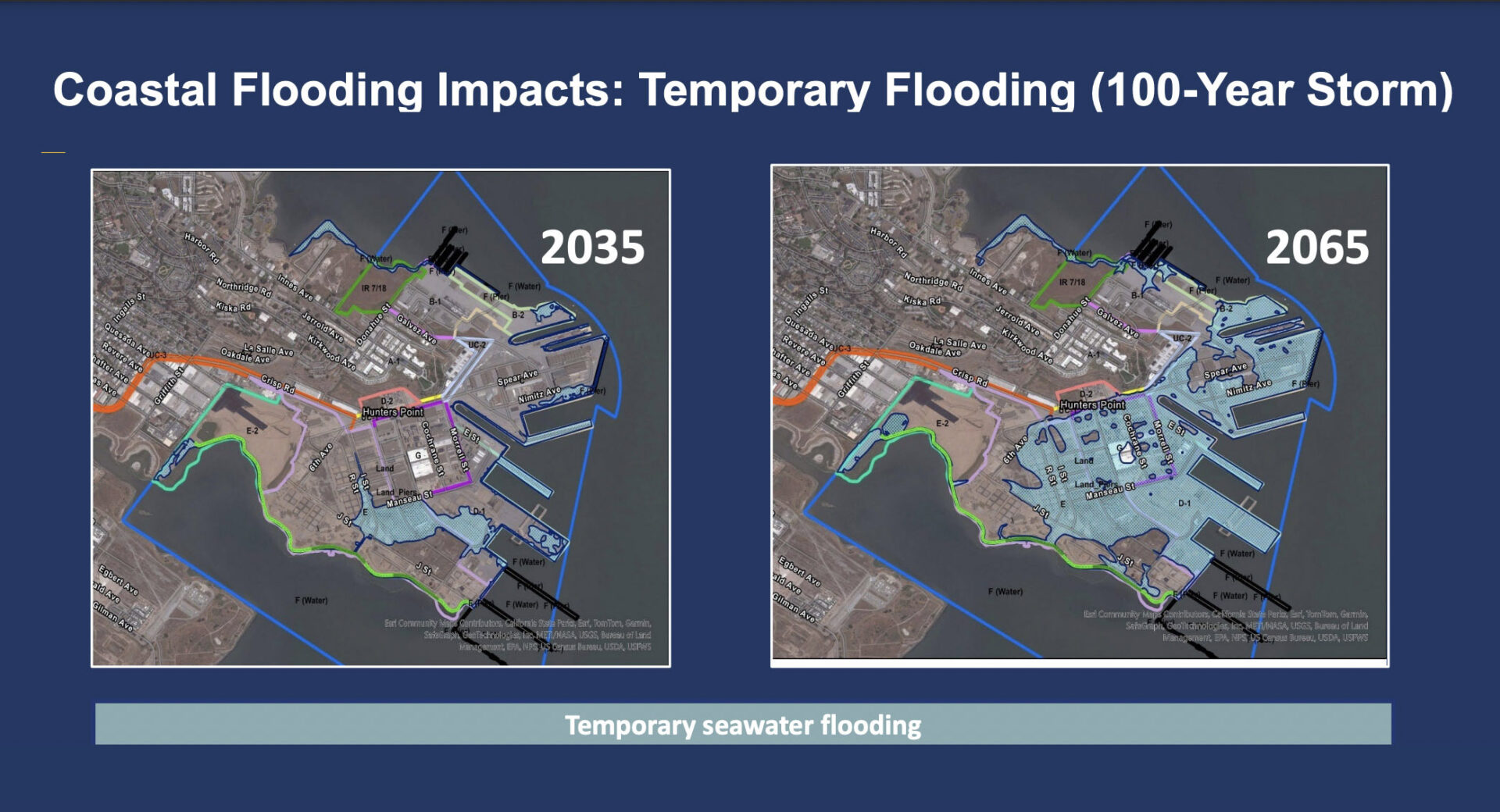

A draft report published late last year by the Navy acknowledges as much, conceding that new exposure pathways will be created and that its existing protections will be insufficient. The report, a five-year review of the shipyard cleanup, noted in its climate resilience assessment that by 2035, contaminated groundwater could surface on Parcel D-1, an area once used for ship maintenance and radiological research. By 2065, groundwater could surface in five other areas and a 100-year storm surge would flood nearly every parcel.

Boxx-Holmes, who grew up in Hunters Point but has since moved to Civic Center, argues it’s not a matter of the future.

“It’s been flooding in 2024,” she says.

The effects of toxic exposure are already ravaging the historically Black neighborhood, says Boxx-Holmes. Contaminated shipyard dirt blows through the chain-link fence daily, dusting nearby areas where people live, work, and play. She says insufficient protections contributed to her asthma, as well as cancer cases splattered across Hunters Point. Shipyard exposure tops out an already high pollution load for the neighborhood from local heavy industry. Seeing the toll of contamination on the community pushed her to move away for her health.

Signs warn people away from the Hunters Point Shipyard. Photo: Audrey Brown

Though she is glad the Navy acknowledged the worsening risks for local people and the environment, she feels certain that worse news is yet to come. After decades of fighting for a thorough cleanup and encountering falsified testing and glacial progress, she has lost trust in regulators and officials to keep her safe.

Many local activists have contested the safety of current containment and treatment measures at the shipyard, citing the elevated levels of heavy metals and radioisotopes — the products of nuclear fission — in people who live nearby. Those findings are being mapped by Hunters Point Biomonitoring Foundation founder Dr. Ahimsa Porter Sumchai, who has found toxin levels most elevated in people who live within a half mile of the shipyard. As early as 1995, a study showed breast cancer rates among women under age 50 are twice the normal level in the area, though the authors did not specify shipyard contamination as the cause.

Regulators are aware that the relationship between the community and those responsible for the cleanup needs repair.

“The Navy previously felt stifled by an acrimonious relationship with the community, so they went through a period of not doing a whole lot of community outreach,” says Mark DeSio, the shipyard’s community involvement coordinator at the Environmental Protection Agency, which oversees the Navy’s cleanup. “But they’re now much more engaged and receptive to doing community outreach.”

The next opportunity for people to give input is an April 22 community workshop.

Overlooked Climate Risks

The Navy’s draft report may not have captured a full picture of the possible climate change impacts coming for the shipyard, according to Kristina Hill, the director of the Institute for Urban and Regional Development at UC Berkeley.

The Navy analysis is based on projections of one foot of sea level rise by 2035 and 3.2 feet by 2065, which align with state estimates. But those projections don’t account for the shipyard sinking, which is likely because it’s built on infill, says Hill. To get a complete picture, projections for subsidence need to be considered along with sea level rise estimates.

In a statement, the Navy said it has not found evidence that the shipyard is subsiding, though it did not specify the extent of its research.

Hill says the Navy also needs to pay more attention to the impact of rainfall. In addition to the gradual rise of baseline groundwater, heavy rains could make the level fluctuate drastically. In some locations around the Bay Area, she has seen groundwater rise by up to six feet.

“I think the impact of wet years is very significant and probably a bigger deal than groundwater rise by 2035,” says Hill. “I would have asked whether the groundwater is rising high enough to be of concern to some of the parcels in a wet year today.”

In a statement, the Navy said it has not identified significant fluctuations or long-term impact on groundwater levels due to rainfall, based on annual data from its monitoring wells. Hill says more frequent sampling, especially after storms, is necessary. It would be relatively easy and cheap, requiring only a $200 monitor capable of tracking the level to the minute. Such granular tracking hasn’t been standard over the last two decades, but Hill says it’s now needed. Honolulu already uses the monitors at a contaminated oil spill site.

That the shipyard is built on infill further complicates matters, says Hill. The mishmash of materials is more compacted in some areas than others, so groundwater could rise inconsistently, with some spots seeing faster rise than the shipyard overall.

Capping Falling Short

Since the 1980s, capping, a method of containing harmful chemicals with a layer of asphalt or soil, has been widely employed. That’s partly because of regulatory red tape: State regulations hamper the construction of new toxic landfills, so it’s necessary to truck toxic waste far away.

“That’s why you’ve seen a proliferation of capping efforts,” says Ian Wren, lead scientist at Baykeeper, a nonprofit watchdog.

A cap is typically either a coat of asphalt or a 3-foot layer of clean soil on top of the contaminated dirt. Sometimes a plastic liner is applied too. “But now that the ocean is coming up underneath these sites, capping no longer makes sense,” says Hill. The Navy’s draft report found that a rising groundwater table would bring water up from below, which could move chemicals out through cracks in the asphalt or holes in the plastic liner.

“I would have concerns about any caps and the opening up of new pathways,” says Wren. “The tide is like a pump. Water in high tide is going to pump under caps and go inland and contaminated water under caps could be siphoned over time into the Bay.”

Wren says capping can be appropriate for some sites far away from so-called sensitive receptors like people or the Bay’s ecosystem, but if people live nearby further cleanup is in order.

With so much uncertainty about future flooding spreading contaminants, plans for redevelopment concern observers. San Francisco intends to build more than 10,000 units of new housing, along with commercial spaces and parks at the former shipyard, in what will be the city’s biggest redevelopment project since the 1906 earthquake.

San Francisco’s Office of Community Investment and Infrastructure is set to take ownership of the shipyard land from the Navy and is overseeing its redevelopment.

“The Office of Community Investment and Infrastructure will not accept the land transfer of the Navy’s Shipyard property until the cleanup is done and is confirmed to be protective of human health and the environment and is implemented to the satisfaction of the regulatory agencies,” said an agency representative in a statement.

Some community activists have called for a more decisive embargo on construction.

“I don’t think we can ever fully clean up that site,” says Michelle Pierce, executive director of the local nonprofit Bayview Hunters Point Community Advocates. “There should not be housing built there.”

The shipyard abuts Shipyard Playground amid newly constructed housing, part of the city’s push to build over 10,000 units of new housing along with commercial spaces and parks in the area. Photo: Audrey Brown

Cleanup Complexities

Today there are a number of possible treatments for cleaning the contaminated soil at Hunters Point, including pump-and-treat systems, which draw water out of the ground to be cleaned before being returned to the soil. Another option bakes contaminated soil into concrete blocks that can be used for rough construction.

Ideally, the soil would be treated on-site, according to Bradley Angel, executive director of the environmental justice nonprofit Greenaction. Digging it up and trucking it away too often exports the contamination to other low income communities of color. Local advocates don’t want to push their community’s problem onto another’s plate.

The Navy has used on-site methods, including pump-and-treat systems and in-situ techniques like injections of bacteria and molasses to break down volatile organic compounds, but without overwhelming success. Much of the contaminated soil is still polluted afterwards and still needs to be dug up and removed, according to Andrew Bain, remedial project manager for the shipyard at the EPA.

Better solutions may be on the horizon. An emerging method called a high temperature electrothermal process, or HET, uses bursts of electricity to heat soil to over 5000 degrees Fahrenheit, which nullifies both volatile organic compounds and heavy metals (the shipyard is rife with both) without using water or generating waste. Unlike most existing solutions, HET zaps multiple pollutants simultaneously. Once it’s over, the soil is left more fertile.

Researchers hope HET can spur cleanup at tricky sites like the shipyard. The method has not yet been deployed against radioactive contaminants, but it could, likely with some tradeoffs, says Bing Deng, the lead author of a Nature Communications study on HET published last October. It would require heating the soil to a much higher temperature, which could compromise energy efficiency and soil fertility.

Though testing is still in early stages, Hill thinks it could be a promising bet for a safe and affordable solution. HET treats toxic soil without moving it, which reduces the exposure risk for people nearby. The method also doesn’t produce a toxic byproduct, like the contaminated water that results from soil washing.

In the meantime, Hill would like to see a local toxics treatment facility get built, which she thinks could streamline cleanup. The Navy disagrees.

“Additional waste treatment and disposal facilities are not required to clean up Hunters Point Shipyard,” said a Navy representative in an email statement.

Hill and Wren believe such a facility would help the whole region.

“There’s a staggering number of contaminated sites around the Bay,” says Wren. Thousands of them dot local coastlines from Treasure Island to Richmond. Creating treatment options closer to home could also lower costs, which could help spur more comprehensive cleanups.

That would be good news not only for Bayview Hunters Point residents, but for the ecology of San Francisco Bay.

“Already these toxic hotspots have contributed to chronic levels of toxicity in the Bay,” says Wren. Researchers hoped Bay pollutants like carcinogenic PCBs might dissipate over time, but that’s not happening, and any near-term gains in cleaning up the Bay could likely be overtaken to sea level rise. Such pollutants build up in Bay wildlife, resulting in current advisories against consuming fish caught from the Bay.

Throughout the region, contamination disproportionately burdens the so-called frontline communities who live just beyond the chain link fence, but local activists caution that people outside the community aren’t impervious to its reach through water. “It’s not just a Hunters Point issue, it’s going to be a whole San Francisco Bay Area coastal crisis,” says Kamillah Ealom, a Hunters Point resident and Greenaction activist. Ealom points out that sea level rise is projected to flood wealthy areas too, such as the Marina District.

“Water wants to move,” says Angel.

More:

April 22: Navy community workshop on its draft five-year review

May 20: Navy update on the ongoing environmental cleanup at the shipyard to the Hunters Point Shipyard Citizens Advisory Committee