Hardscapes That Filter Rain

Most roads, sidewalks, and parking lots are designed to shuttle stormwater and other runoff straight toward drains. Since concrete and asphalt are impervious, or impermeable, water runs off them instead of through them — in some cases carrying oil, microplastics, and other contaminants straight to bodies of water like the San Francisco Bay.

Climate change is making winter storms more intense, leading to heavier runoff that picks up more pollution and is more likely to overwhelm existing stormwater infrastructure. A solution that local cities and regulatory agencies are increasingly considering is replacing these hard surfaces with porous alternatives that let water pass through into the underlying soil.

There are four main categories of permeable paving — porous asphalt, pervious concrete, permeable pavers, and grid pavements — and each has a specific use case or application, explains Peter Schultze-Allen, a senior technical scientist with Oakland environmental consulting firm EOA, Inc.

Other Recent Posts

Building Sustainably with Mass Timber

This building method can help clear forests of smaller trees that burn easily while also reducing the carbon footprint of new homes and offices.

The Gray-Green Alchemy of Baycrete

Baycrete is a nature-based hybrid of concrete, shell, and sand designed to attract oysters and create shallow water reefs in SF Bay.

Tools Tweak Beaver Dams

Humans find ways to co-exist with beavers, tweaking dams to prevent flooding and create more climate resilience.

Hopes and Fears for Sierra Snowpack

February’s drought and deluge confirms that uncertainty may be a given for California snowpack, western water supply, and wildfire risk.

Errands by E-Bike

Electric cargo bikes are climate-friendly car replacements for everyday activities, from taking the kids to school to grocery shopping.

A Rare Plant Tough Enough to Save the Future Bayshore

Sea-blite can thrive in adverse conditions, buffer shores from waves, hold sand and soil in place, and clamber up eroding cliffs.

Reforming Rules to Speed Adaptation

Bay Conservation and Development Commission to vote early this year on amendments designed to expedite approval of climate projects.

Diagram: I-Stock

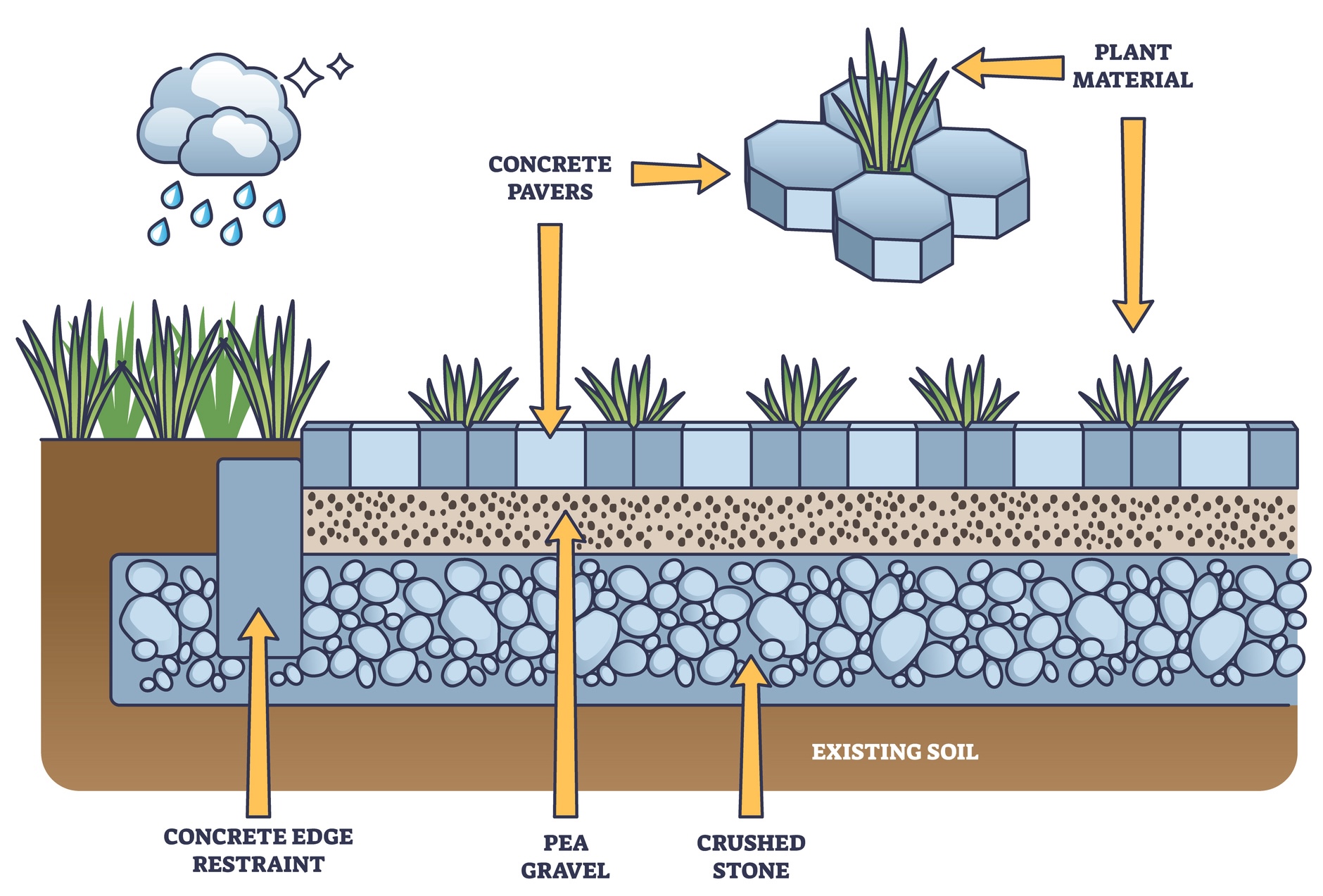

Porous asphalt is for roadways. It’s missing much of the fine aggregate in the spaces between larger bits of stone and gravel, leaving tiny voids for water to flow through. Grid pavements — plastic or concrete grid systems packed with gravel — are ideal for lower-traffic areas like driveways and parking lots. Permeable pavers, sometimes called permeable interlocking concrete pavers, are small concrete pavers that are either porous themselves or that have joints between them filled with gravel or sand. They can be used for both walkways and roadways.

Pervious concrete, finally, may be the most interesting material because of the many places it can be employed: parking lots, sidewalks, curbs, gutters, even roadways. Like porous asphalt, it’s created by omitting fine aggregate (sand) from the mix.

Grid pavement in Berkeley. Photo: EOA

Within this category are two subtypes, says Schultze-Allen: pre-cast slabs, which ensure uniform permeability but offer less flexibility and may be used in sidewalks, parking lots, gutters, and walkways; and poured-in-place, which is applied wet and can take any shape like traditional concrete. “It has flexibility, so if you have curbs or things like that, you can form it on-site to whatever the design is,” he says.

Both types offer a high infiltration rate compared with permeable pavers, and are generally more cost-effective per square foot, says Nancy Crowley, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission press secretary. But there is a drawback: aesthetics. By its very nature, pervious concrete isn’t as smooth as traditional concrete. It can look rough or unfinished. “It is more often proposed for projects where aesthetics are not the primary driver,” Crowley says.

Mission Creek stormwater park in San Francisco. Photo: SFPUC

Nonetheless, pervious concrete did find a home at the city’s new Mission Creek Stormwater Park, a high-profile showcase of permeable materials and designs set right on the waterfront. “The surface allows rainwater to soak through the pavement,” says Crowley, “with any excess water routed to nearby planted stormwater treatment areas that help filter runoff before it reaches the Bay.”

San Francisco has installed approximately 410,000 square feet of permeable paving at 107 sites since 2010, she notes. Another 175,000 square feet at 36 sites is approved or under construction.

Editor’s note: Pervious concrete is one of the engineering plants, animals, and materials being featured in KneeDeep’s mini-series on the building blocks of climate adaptation. You can also read our features on beavers, sea-blite, mass timber, and baycrete, or send us ideas for other materials to cover.