Helping Farmworkers Navigate Ugly Weather and Raids

Belinda Hernandez-Arriaga. Photo: ALAS

Relentless misfortunes have impacted coastal farmworkers in recent years — climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, a mass shooting at a mushroom farm with “deplorable living conditions,” and more.

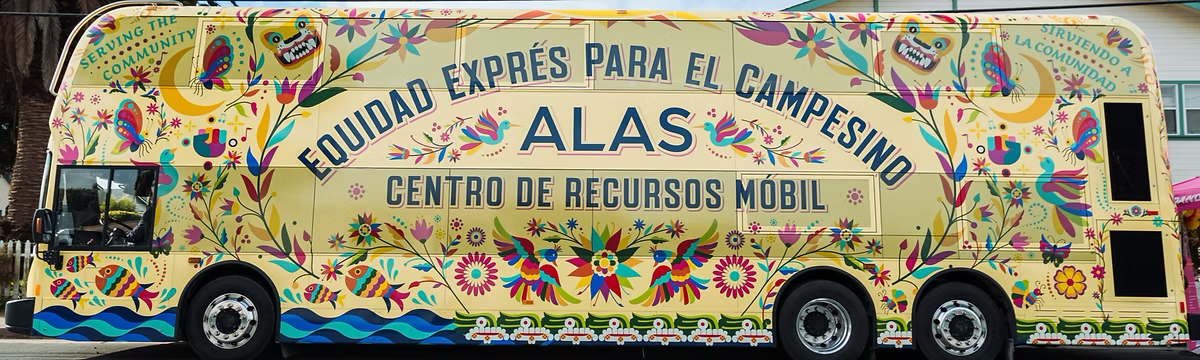

That’s where leaders like Belinda Hernandez-Arriaga, executive director of ALAS (Ayudando Latinos A Soñar), are trying to fill gaps in health, immigration, and education services for Latinos in Half Moon Bay. The nonprofit’s Farmworker Equity Express Bus, a “mobile resource center,” brings Wi-Fi, nutrition services, tutoring, and counseling directly to workers in the fields.

Hernandez-Arriaga, who is originally from Texas and the granddaughter of a farmworker who hauled rice, is a trained social worker and professor. Her research focuses on cultural interventions to address trauma and farmworker mental health. She’s a member of Bay Area Border Relief and in the San Mateo County Women’s Hall of Fame. The county Board of Supervisors recently recognized her and ALAS for their work.

ALAS Farmworker Outreach Team in green hoodies bring food and resources to workers in the field on coastal farms. Photo: ALAS

Hernandez-Arriaga is currently responding to the most recent challenge for the community: the Trump administration’s mass deportation efforts. ALAS hired a security guard after receiving postcards saying “Have your bags packed — Trump’s coming!” Volunteers also noticed someone aggressively video-recording clients at ALAS headquarters.

In August, Hernandez-Arriaga spoke with KneeDeep about how her organization is addressing the difficulties these farmworkers face.

Q: How are farmworkers in coastal areas navigating ICE roundups?

So scared, so scared. The anxiety, the depression, the fear is real. Rounding up people in plain sight is making people physically and emotionally ill.

We’re definitely doing a lot more in the counseling mental health field. One of the things we believe is important in these areas is mobilizing the cultural arts as a centerpiece for healing — guitar classes, accordion classes, doing art, painting, singing, breaking bread.

Q: How have changing weather conditions on the coast affected farms?

Other Recent Posts

Reforming Rules to Speed Adaptation

Bay Conservation and Development Commission to vote early this year on amendments designed to expedite approval of climate projects.

Warner Chabot Shifts Gears

After 11 years at the helm of the Bay Area’s leading science institute, its leader moves back into the zone of policy influence.

Is Brooklyn Basin Emblematic of Regional Development Vision?

The 64-acre waterfront development adds thousands of new housing units to one of the world’s most expensive places, but questions remain about its future.

Coordinate or Fall Short: The New Normal

Public officials and nonprofits say teaming up and pooling resources are vital strategies for success in a climate-changed world.

Pleasant Hill Gets Sustainable Street Improvements

An intersection redesign with safer bike lanes earned a national Complete Streets award, while sparking mixed reactions from drivers.

Six Months on the Community Reporting Beat

The magazine worked with four journalists in training from community colleges, and began building a stronger network in under covered communities.

Rio Vista Residents Talk Health and Air Quality

A Sustainable Solano community meeting dug into how gas wells, traffic, and other pollution sources affect local air and public health.

Every year, we’ve seen different ways that climate change has an impact, but I’ve also seen how people don’t really think [about] how it affects our farmworkers. When it’s flooding, they don’t have income. Maybe they have a place to live, but they don’t have food [nor] access to basic needs.

We’ve been advocating for economic relief. Taking food to them has been a big change in our program, like taking fresh fruits and veggies, eggs and milk. Our farmworkers that grow our veggies are the same ones that we have to turn around and give food to. That’s so hard to take in.

Q: Is the dream of a better life in California still viable given our changing climate?

They’re out for days of work. They’ve lost wages. Crops are lost. Fires displaced folks. There’s no stipends or grants that come in during that time.

When COVID happened, we saw that there was economic relief, and how that really helped farmworkers.

People [farmworkers] don’t necessarily think about what they are doing to sustain themselves. That’s where our organizations, foundations, political leaders really can be at the forefront.

Photo: ALAS

Q: What motivates you to continue your work despite these challenges?

We’ve [gotten] letters from people cheering them [immigrants and farmworkers] on, saying, “Thank you. We appreciate you. We value you.” And for them, they see, “There’s people that really do care. We aren’t invisible.”

I’ll never forget [one worker] we were taking lunch to told me, “In 40 years, no one has ever given me so much as a bottle of water in the field.”

The community makes art to express attitudes about farmworkers. Photo: ALAS

How do you go in one moment in time from, “You’re a champion, a hero, you’re rallied around by our whole country,” and at another time it’s OK for them to be rounded up and running for their lives in the fields? They are doing work that many people would never do and never want to do. They do it because it gives them joy to know that other people are going to be able to eat because of them.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.