What I Learned About Sea Level Rise at a Regional Summit

Cris Criollo of the Multicultural Center of Marin explains sea level rise during a Bay Adapt Summit tour in September 2025. Photo: Paige Green

In mid-September, hundreds of climate activists, local and regional planners, environmental scientists, engineers, and academics descended on the Exploratorium on San Francisco’s waterfront for the Bay Adapt Summit hosted by the Bay Conservation and Development Commission.

The annual conference honors climate innovators for their work and features presentations, speeches, and panels on everything from sea level rise to permitting for adaptation projects and funding at a time when federal grants are up in the air.

As someone new to the Bay Area — I moved to San Francisco from Chicago in June — I decided to turn the event into my own “Sea Level Rise for Dummies” guide, asking the experts what a newbie should know.

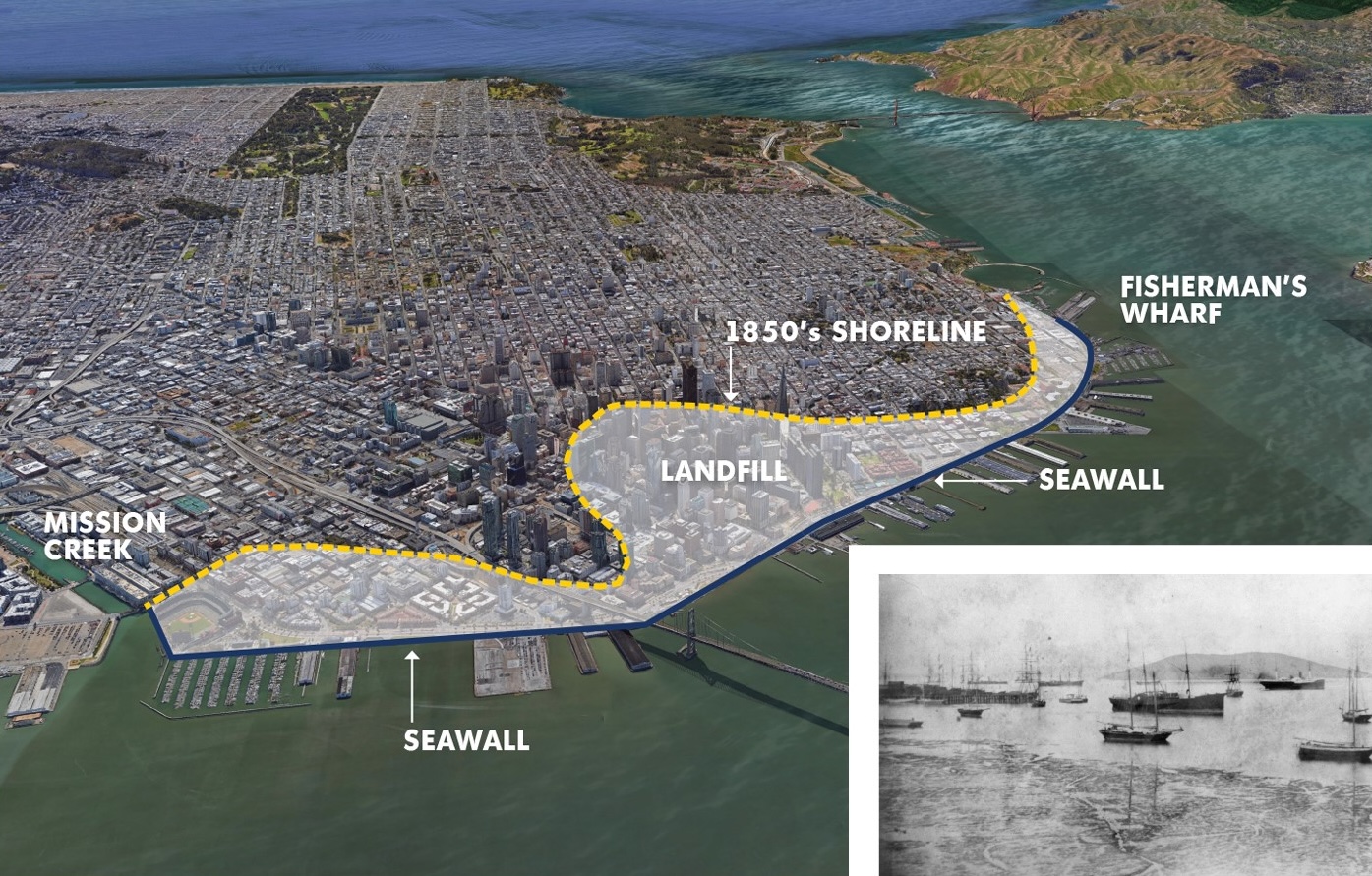

Luiz Barata, a senior planner for the Port of San Francisco and one of the summit’s honorees, didn’t hesitate: “Most of the shoreline is bay fill, so it is where water used to be, and with sea level rise and flooding, that’s where the water’s going to go.”

Planner and organizer Keta Price, the San Francisco Estuary Institute’s Jeremy Lowe and the Port of San Francisco’s Luiz Barata were honored at the 2025 Bay Adapt Summit. Photo: Ida Høyrup/Explatorium

Others mentioned similar concerns about development and housing in low-lying areas “reclaimed” from the Bay. And while simply building a bunch of sea walls along the shoreline might seem like a good idea at first, “that doesn’t really protect it,” says Gabriel Kaprielian, a designer and architecture professor at Cal Poly.

Building walls, according to Kaprielian, could have the unintended consequence of turning areas close to the Bay into de facto lagoons when it rains or when groundwater infiltrates, because those places will eventually be below sea level.

“You don’t think about it as much because it’s a slow moving thing here, as opposed to on the East Coast [where] you see the compound effects a lot more because of the storms,” he says. “But it’s coming here, too. We’ve been getting more of those atmospheric rivers, so that’s going to definitely make things worse.”

Another key element of flooding and sea level rise for the Bay Area? Neighborhoods in the hills might think they’re fine, but “if something gets flooded in one spot, that affects the whole system” of roads and public transit in the region, Kaprielan notes.

Where the Bay Area invests in solutions to sea level rise is also a point of contention.

The Port of San Francisco, for example, has a multi-decade Embarcadero Seawall Program designed to protect places like the Ferry Building from an estimated three to seven feet of sea level rise expected by 2100.

Areas that have been filled along San Francisco’s downtown shoreline. The seawall transformed 500 acres of tidal flats into new land. Graphic: Port of SF

But Hollis Pierce-Jenkins, executive director of nonprofit Literacy for Environmental Justice, is worried about what could happen to other neighborhoods that don’t attract the same level of tourism and business development. The city will pay up to make sure the Embarcadero stays above sea level, but other places might not be so lucky, especially lower-income communities along the shore farther south, like Bayview-Hunters Point.

And vital to all efforts to adapt to sea level rise, several people point out, is education, which can empower communities to advocate for themselves and put pressure on local and regional government agencies to act.

“The challenge is the mental resistance to change that I often experience. It’s not negative, it’s just people are unaware of what the benefits could be … breaking through that wall that people have, where they think one way but find out, ‘This is how it actually works,’” says Shy Walker, director and founder of environment education group Ninth Root. “That’s just been the biggest challenge — changing the tides of how people think about themselves in relation to space and place.”

Jeremy Lowe, another summit honoree and a senior environmental scientist at the San Francisco Estuary Institute, says the most important thing to know about sea level rise is that it’s a reality, and the region has to take the time now to prepare for it.

“It’s been happening, it’s happening now and it’s going to happen in the future,” Lowe says. “This is really an opportunity to make changes, not just to protect ourselves from sea level rise, but to make [the waterfront] better.”

Other Recent Posts

Building Sustainably with Mass Timber

This building method can help clear forests of smaller trees that burn easily while also reducing the carbon footprint of new homes and offices.

Hardscapes That Filter Rain

Heavy rain can overwhelm storm drains and pollute waterways, but materials like permeable pavements help filter runoff and prevent flooding.

The Gray-Green Alchemy of Baycrete

Baycrete is a nature-based hybrid of concrete, shell, and sand designed to attract oysters and create shallow water reefs in SF Bay.

Tools Tweak Beaver Dams

Humans find ways to co-exist with beavers, tweaking dams to prevent flooding and create more climate resilience.

Hopes and Fears for Sierra Snowpack

February’s drought and deluge confirms that uncertainty may be a given for California snowpack, western water supply, and wildfire risk.

Errands by E-Bike

Electric cargo bikes are climate-friendly car replacements for everyday activities, from taking the kids to school to grocery shopping.

A Rare Plant Tough Enough to Save the Future Bayshore

Sea-blite can thrive in adverse conditions, buffer shores from waves, hold sand and soil in place, and clamber up eroding cliffs.