Scientists Nail Climate Links to Extreme Events

While a supermajority of Americans finally believe we are warming the world, a 2020 Yale Climate Opinion survey shows that most people still aren’t very worried about it. “Climate change is abstract to them,” says UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain. “They don’t connect it to their personal lives.”

But Californians do. Reeling from a decade of record-shattering drought, heat waves, and wildfires, people in the Golden State overwhelmingly tell Public Policy Institute of California pollsters that the effects of global warming have already begun. Indeed, Swain confirms, researchers can now link climate change with some of today’s extreme events beyond a reasonable doubt.

“Climate change is a slow process, it kind of sneaks up on you, but we’re at the point where it’s not so sneaky: it’s here now,” says Michael Wehner, a Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory climate researcher and a lead author on both the latest and the next Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports. “We’ve been able to quantify effects on the weather, and those have effects on our lives.”

Attributing a particular extreme event to climate change is a young field that has seen great gains in a short time. “It all started in 2002, when Myles Allen’s house got flooded,” Wehner recalls of his colleague at the University of Oxford in England. “He lived too close to a river.” Allen was sure climate change had played a part in his predicament, sparking him to pin down global warming’s contribution to extreme events.

He got his chance just a year later, when Europe suffered an intense heat wave that withered crops and killed more than 30,000 people: Allen co-authored a 2005 study in the journal Nature showing that climate change had doubled the risk of this catastrophe. “This was the first quantitative statement on attribution of extreme events to climate change,” Wehner says.

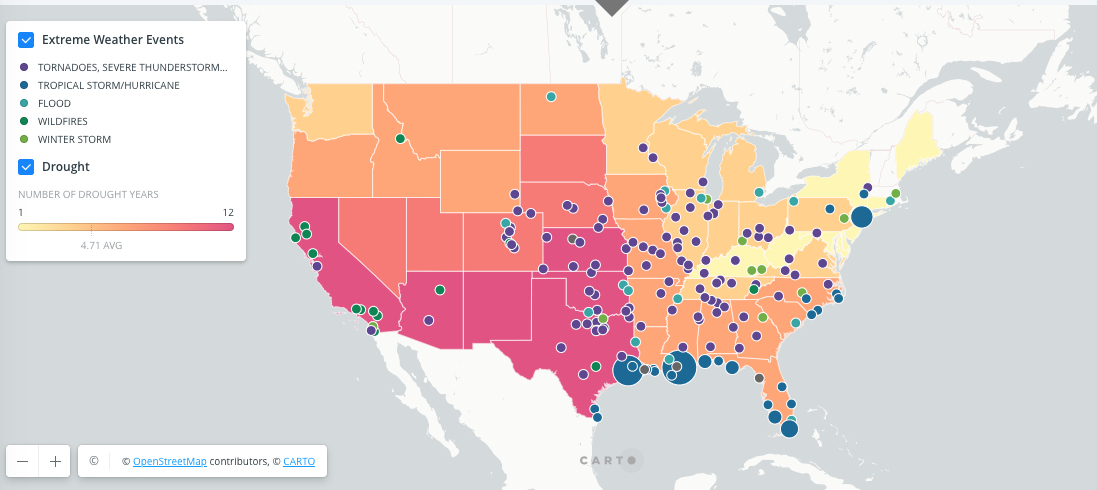

Billion dollar extreme events between January 2000 and December 2020. Source: Center for Climate and Energy Solutions & NOAA Climatic Data Center

“Climate change makes the most intense storms more intense, and it’s raining more in the most intense storms.”

To assess whether ― and how much ― climate change influenced an individual event, researchers combine historical trends with climate models. The latter are run both without and with the extra carbon people have pumped into the atmosphere, thus comparing what would have happened without global warming to what actually happened. This shows that climate change already makes some extreme events more severe and/or more likely, even tipping them over the edge between possibility and reality.

The clearer an extreme event’s connection with temperature, the higher our confidence in its attribution to climate change. “Any time there’s a record heat wave, it has a very distinct human fingerprint,” says Swain, lead author of a 2020 primer on attributing extreme events to climate change in the journal One Earth. “That’s a slam-dunk example.”

Next on the confidence scale for individual events are the wild swings in precipitation that cause intense rainstorms at one end and severe droughts at the other. While these events have multiple influences, the climate signal is still relatively easy to tease out. “Hydrological extremes are strongly related to the level of warming,” Swain says, telling me this is because a temperature increase of one degree Celsius boosts the atmosphere’s capacity to hold water vapor by seven percent. “Wow!” I exclaim. “That is a wow,” he agrees.

This escalating impact of warming on atmospheric moisture worries Swain even more than the warming itself. The 1.3-degree Celsius rise in average global temperature since the 1880s translates to a nearly 10-percent bump in how much water the atmosphere can hold. The impact of this is huge. “It increases the propensity of the atmosphere to act as a sponge and suck up moisture,” Swain explains. “A thirstier atmosphere increases the flood risk when it does rain, and also increases drought and wildfire risk.”

And Wehner thinks climate change may make the atmosphere even thirstier than expected. He and his colleagues discovered that in hurricanes like Katrina and Harvey, the rainiest parts greatly exceeded the seven-percent rule. “Climate change makes the most intense storms more intense, and it’s raining more in the most intense storms,” he says. Likewise, his current work on atmospheric rivers in California suggests that these storms can also dump even more rain than predicted.

The bottom of the confidence scale for individual extreme events includes wildfires, which are among the trickiest to attribute to climate change. “Wildfires are hard,” Wehner says. People affect fire risk in so many ways, from suppression to land-use practices, that it’s difficult to pick up on the climate signal for a given conflagration.

That said, Wehner believes climate change was a factor California’s latest and worst wildfire season, when nearly 10,000 fires burned more than 4.2 million acres. In particular, he suspects global warming influenced the lightning complex blazes that raged through the coast ranges flanking the San Francisco Bay, forcing more than 100,000 people to evacuate and shrouding many more in a pall of acrid smoke that spread across the country.

“It’s quite obvious to me that fire risk increases with climate change,” Wehner says. “Heat dries out plants, leading to an earlier fire season ― and if it’s flammable earlier, you’re going to have more fires.”

Mitigating carbon emissions is obviously the only real fix for global warming. But in the meantime, understanding how climate change affects extreme events in specific places can inform decisions by regional planners and land-use managers, who must adapt to the changes that are already here and prepare for those yet to come. “We certainly know enough to act,” Wehner says, noting that he is speaking for himself rather than in any official capacity. “I think we’re at that point.”

Swain concurs. “It gets a little old as a climate scientist to be constantly delivering bad news,” he says. “The good news is there’s a lot we can do about it.” To help speed that effort, Swain is collaborating with the Nature Conservancy as their first California Climate Fellow.

“We can’t stop the extreme events that climate change is forcing, but we can plan for them,” says the Nature Conservancy’s Dick Cameron, whose focus is managing land to provide climate solutions that benefit both the environment and people.

Ways to accommodate deluges from atmospheric rivers include creating bypasses and restoring wetlands to slow floodwaters down, taming their destructive potential. And we can get ready for droughts by actively recharging groundwater during wet years as well as by adjusting agricultural practices. Planting cover crops ― like the rows of brilliant yellow mustard between wine grape vines ― can boost the soil’s capacity to retain water.

Another agricultural practice that could be adjusted is overplanting perennial crops like nut trees. Unlike annual crops, which can be fallowed when water is scarce, nut tree orchards are thirsty even during droughts. But perennials could be capped to keep their water use from outstripping groundwater recharge rates, making these crops sustainable during dry years.

Adaptations to California’s new era of mega-wildfires vary by ecosystem and whether or not people live there. In forests, Cameron recommends managing fuel with prescribed burns as well as by thinning small trees and brush. And he recommends defensive measures in populated areas of the coast ranges, where fire is driven by fall winds over chaparral and oak savanna that are basically tinder after the hot, dry summer. Home protections include fire-proof materials and a non-combustible surrounding that serves as a fire break. On a larger scale, riparian zones, vineyards, and orchards can buffer communities by slowing fires.

“The impacts of climate change have come faster and more severe in California than expected,” Cameron says. “It’s crazy and it’s scary.” He fears extreme events will soon spiral further out of control. “The atmosphere is loaded for these kind of events ― there are time bombs in the system,” he says. “We need to make investments to help people and nature adapt.”

More

- Carbon Brief-Interactive Map on How Climate Change Affects Extreme Weather

- 2020 One Earth Primer by Daniel Swain

- Billion Dollar Extreme Events Map – Center for Climate & Energy Solutions

First published by Estuary News Group, June 2021