Split Verdict Over State of the Estuary

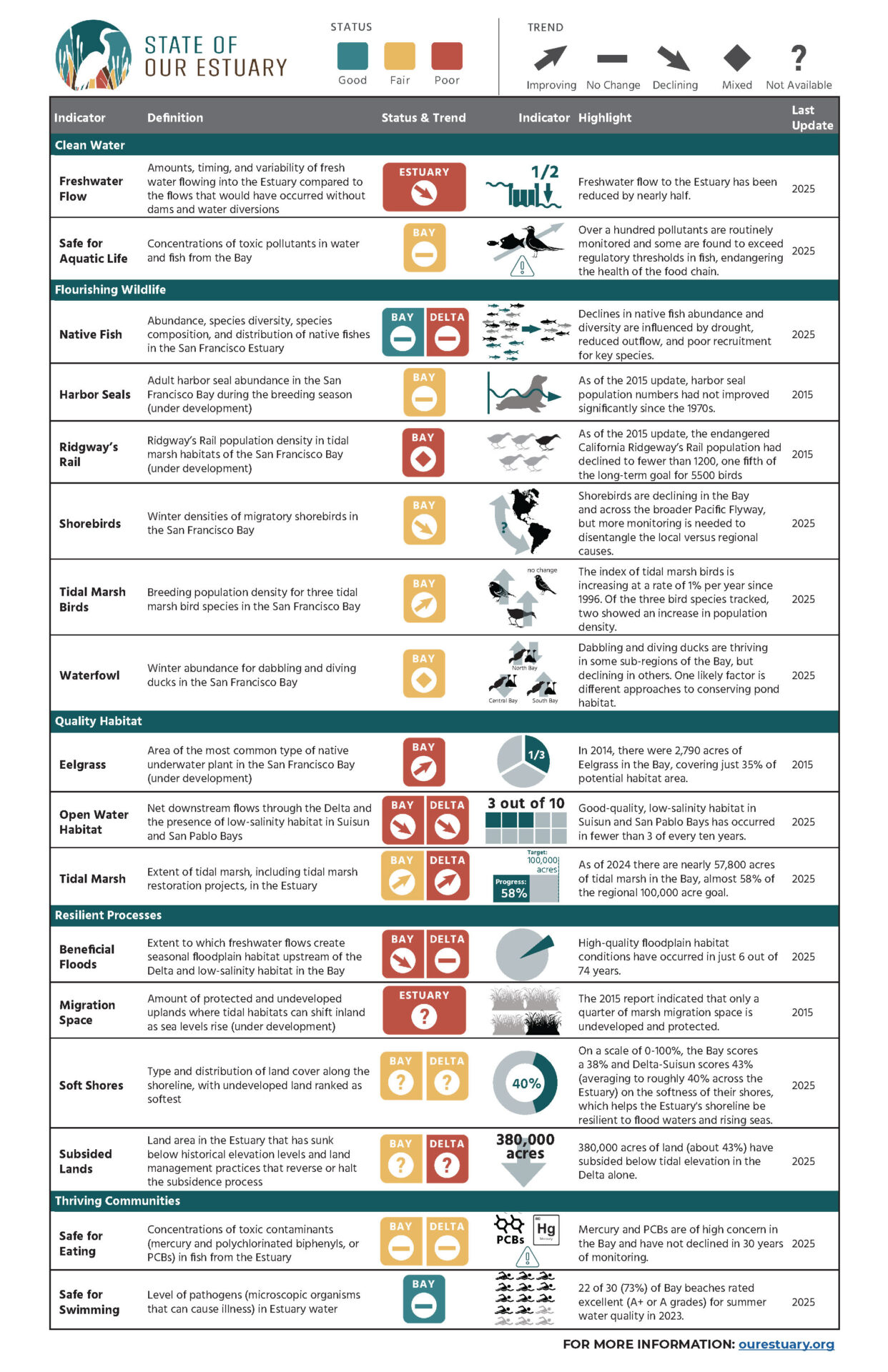

The 2025 State of Our Estuary assessment, released this fall at a regional conference, takes the pulse of the San Francisco Estuary in 17 indicators. It’s a health checkup for over 38 million acres of interconnected rivers, bay, and marsh, revealing which restoration efforts are paying off and where our waterways are still struggling to catch their breath.

The indicators are the visible, measurable bits that scientists can count, test, and track over time: bird counts, acreage of eelgrass, concentration of mercury in an estuary fish. Sometimes, the canary in the coal mine is the marsh-dependent Ridgway’s rail — whose numbers have declined to under 1,200 largely due to urbanization of the shore.

The Bay itself earned fair marks and appears stable. Not stellar, but holding steady. Where things are improving, the credit goes to big moves: large-scale habitat restoration projects and tougher pollution regulations. Wetlands are creeping back along the margins: the Bay now has 57,800 acres, while the Delta has gone from 8,000 to 13,000 acres over five years. In many cases, tidal marsh birds are following.

Cleanup efforts mean the Bay is mostly safe for swimming these days, a victory that would’ve seemed improbable decades ago when industrial waste and toxic slag flowed freely into the water. But legacy pollutants like mercury persist, stubborn reminders of California’s mining past that haven’t declined in 30 years of monitoring.

Other Recent Posts

Tools Tweak Beaver Dams

After witnessing fire disasters in neighboring counties, Marin formed a unique fire prevention authority and taxpayers funded it. Thirty projects and three years later, the county is clearer of undergrowth.

Reforming Rules to Speed Adaptation

Bay Conservation and Development Commission to vote early this year on amendments designed to expedite approval of climate projects.

Warner Chabot Shifts Gears

After 11 years at the helm of the Bay Area’s leading science institute, its leader moves back into the zone of policy influence.

Is Brooklyn Basin Emblematic of Regional Development Vision?

The 64-acre waterfront development adds thousands of new housing units to one of the world’s most expensive places, but questions remain about its future.

Coordinate or Fall Short: The New Normal

Public officials and nonprofits say teaming up and pooling resources are vital strategies for success in a climate-changed world.

Pleasant Hill Gets Sustainable Street Improvements

An intersection redesign with safer bike lanes earned a national Complete Streets award, while sparking mixed reactions from drivers.

Six Months on the Community Reporting Beat

The magazine worked with four journalists in training from community colleges, and began building a stronger network in under covered communities.

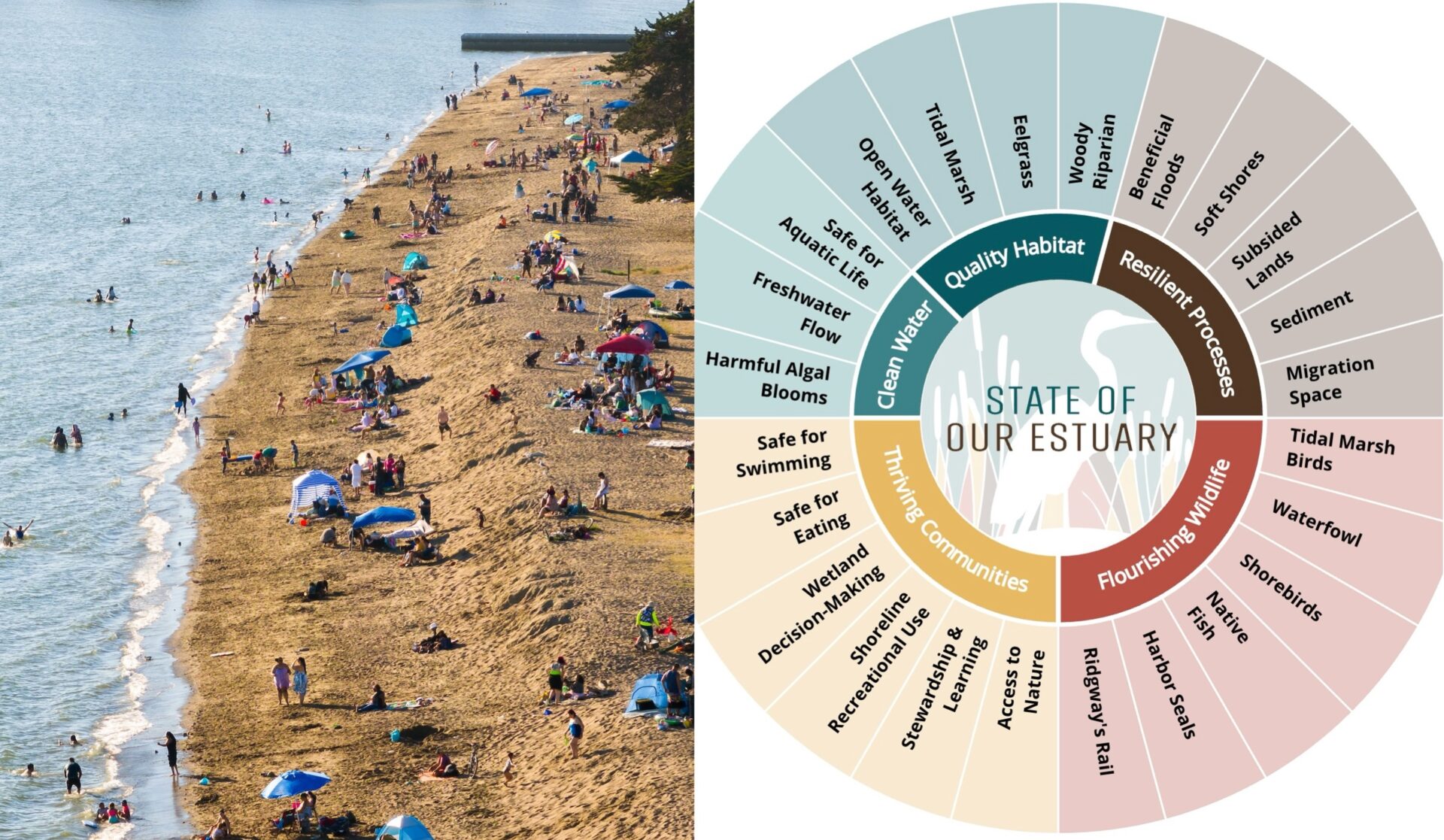

17 indicators tracked by the San Francisco Estuary Partnership to assess the health of the Estuary, including swimmability at places like Crown Beach, Alameda. Photo: Maurice Ramirez

The Delta, meanwhile, is the troubled student in the back: generally poor grades, trending downward. It’s more subsided than the Bay — about 43% of the Delta has sunk below tidal elevation, creating a big engineering challenge for the future. Freshwater diversions to cities and farms have created “chronic artificial drought conditions,” reducing flow to the Estuary by nearly half.

When water is siphoned away year after year, it adds up to an ecological overhaul. With less fresh water coming from the upper watershed, floodplains don’t flood, and wetlands in Suisun and the North Bay don’t get their regular pulse of low-salinity water. As a result, fish and birds lose seasonal habitats and nurseries. Without them, the Delta’s native species are disappearing, replaced by invasives better suited to the new, more stagnant regime.

So what does this mixed report card mean for the future? Here’s the good news: where intervention is happening, it’s working. Wetlands restored, pollution regulated, habitat expanded; these efforts show up in the data as tangible improvement. The challenge is that not every part of the system is getting that level of attention. And in California, where water is always the story behind the story, the choices we make about flows and fresh water demand will determine whether the Delta rebounds or slides further into ecological debt.