Is Brooklyn Basin Emblematic of Regional Development Vision?

A 64-acre development on the Oakland waterfront adds thousands of new housing units to one of the world’s most expensive places, but has it contributed to regional resilience?

A small city of eight-story apartment buildings has popped up at Brooklyn Basin on the East Oakland waterfront. Just looking at it, you wouldn’t know this development — which will eventually include a mix of 3,235 luxury and 465 affordable units when all is said and done — is the result of a 20-year push for more housing in one of the world’s most expensive regions.

Both the Bay Area and the state have grappled with a desperate need for more affordable housing for decades. In recent years, Gov. Gavin Newsom has signed a series of laws requiring cities to adopt plans outlining how they will provide enough housing for residents of all income levels. These laws also streamline approval for affordable housing developments and allow the state to intervene in cities that repeatedly fail to hit their housing construction goals.

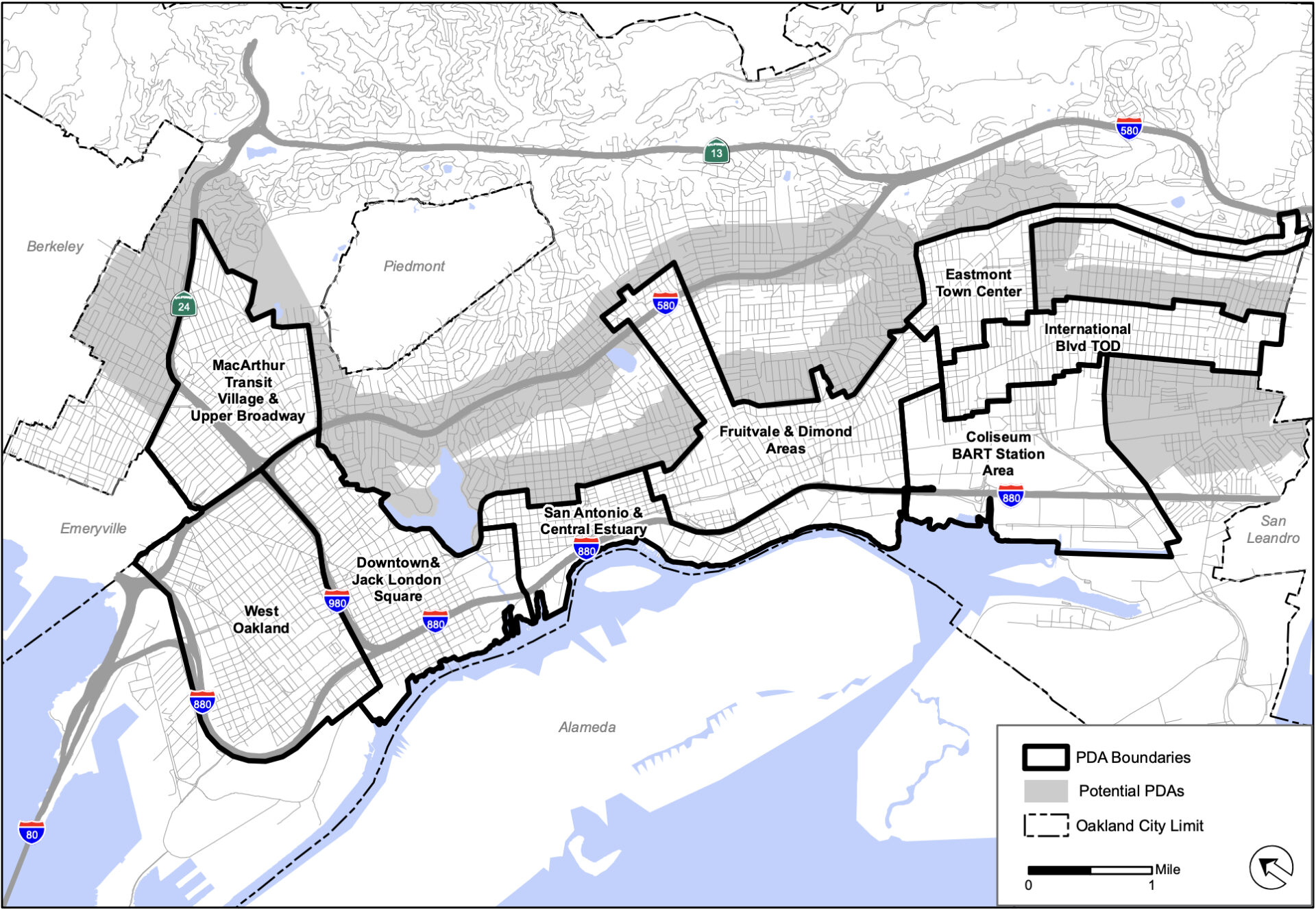

Another layer of influence over the location of new housing and other infrastructure can be found at the regional level. While the Bay Area’s planning agencies may have good intentions when they identify places like Brooklyn Basin as “priority development areas,” experts say that once a project wins approval, how it proceeds is still largely left up to the developer.

This winter and spring, KneeDeep will be examining several PDAs around the Bay to see how they have grown and to compare the reality on the ground to how local and regional plans envisioned them. Our goal is to reassess what planning on a regional scale can and cannot accomplish, especially when it comes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing climate resilience.

A case in point is Brooklyn Basin, which I visited for this story in early January. To date, all 465 affordable units are up and occupied, but the now densely populated neighborhood still feels deeply unfinished, with vacant lots awaiting more new apartment buildings and questions remaining about the parkland and retail space outlined in the development’s plan, and the site’s future vulnerability to sea level rise.

Waterfront housing at Brooklyn Basin. Photo: Duncan Agnew

History of a Harborfront Site

About a mile and a half east of Jack London Square, the 64-acre Brooklyn Basin property juts into the Oakland Estuary next to the Lake Merritt Channel and across from Coast Guard Island.

The only building on the site for decades was the 9th Avenue Terminal — a large pre-war industrial building that stored and processed break-bulk cargo brought to the Port of Oakland. But with the rise of other forms of shipping, the building’s use slowly petered out, until Signature Development Group came along in the mid-2000s and proposed knocking it down and redeveloping the area with housing and retail space.

But the Oakland Heritage Alliance had other ideas. The last surviving terminal built as part of a harbor bond approved by Oakland voters in 1925, the facility was eligible for landmark status, according to the Alliance, which advocated for preserving at least half the building as a public gathering space of some kind. Signature and the city, however, agreed to save just 20% of the building. The Alliance filed a lawsuit, which was ultimately dismissed.

“They still allowed the demolition of 80% of it. [All] we were saying was that this building should be looked at as a potential public resource, and various models were suggested, such as Chelsea Pier in New York City, the Ferry Building in San Francisco — the concept being a public space with several markets in it,” says Arthur Levy of the Alliance. “But the developer was very opposed to that, and they said it was infeasible.”

The refurbished 9th Avenue Terminal, with the same facade as before but an 80% smaller footprint. Photo: Duncan Agnew

In the late 2000s, the City of Oakland completed a series of development agreements and environmental impact reports concerning the site, and Signature initially won approval to build 3,100 housing units in a project that it branded Brooklyn Basin. As part of the development deal, the city required 15% of the units to be allocated to affordable housing, and selected MidPen Housing to construct it.

Today at Brooklyn Basin, four affordable apartment buildings are complete, with their units available for households making between 20% and 60% of the area median income to rent. According to data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the State Treasurer’s Office, and the California Department of Housing and Community Development, that income range for a household of four in Alameda County is between $31,960 and $95,880.

Meanwhile, market-rate units in other buildings on the property are on sale starting at $275,000. Some of them also offer rentals, including a mix of studios, one-bedroom, two-bedroom, and three-bedroom apartments and two-bedroom townhomes.

Some of the new housing at Brooklyn Basin. Photo: Duncan Agnew

What’s in a PDA?

As this project came to fruition over the last two decades, regional government agencies were also undergoing a transformation in their approach to urban planning — which can be seen in the results of Brooklyn Basin, whether intentional or not. In the mid-2000s, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, Association of Bay Area Governments, Bay Conservation and Development Commission, and the Bay Area Air District began to explore the idea of designating PDAs — neighborhoods and open spaces ideal for development because of their capacity to handle new housing and their existing access to regional public transit infrastructure.

According to Mark Shorett, a principal planner with MTC/ABAG who collaborates with local governments on future development, PDAs can be both large and small in scale. Some might be located in neighborhoods already developed “relatively intensely” but with some capacity for more people, while others might be large former industrial areas.

“There are certain places where there is a particularly great opportunity for reuse, like where you have a former military base or a former large-scale activity that is currently vacant or in the process of being sold,” says Shorett, citing Mare Island in Vallejo, the Concord Naval Weapons Station, the former naval air station in Alameda, and Brooklyn Basin as examples. “There are more of them immediately around the Bay in part because of the concentration of federal facilities relatively close to the [shore] for World War II.”

He also notes that some parts of the South Bay mirror this trend because of old, large footprint industrial buildings from the first tech wave that are now obsolete or being consolidated.

Local jurisdictions are tasked with nominating priority development areas to MTC, which maintains an interactive map of the more than 200 PDAs it’s approved in partnership with city governments around the Bay so far. PDAs are generally defined as neighborhoods where at least half the area is within half a mile of transit, which includes bus stops, rail stations, and ferry terminals.

“PDAs are a key piece of the Bay Area’s regional growth framework,” MTC’s website notes, “to create an equitable, prosperous future for all Bay Area communities and make the best use of available resources.”

As shown in the map of Oakland PDAs below, Brooklyn Basin is just one small section of the wider San Antonio PDA. Within PDAs are also “priority development sites,” which Shorett describes as “individual parcels or sets of parcels that cities have identified as the highest opportunity sites for future housing,” like Brooklyn Basin.

Brooklyn Basin, though, isn’t exactly transit rich, as some in the community point out. The only public transit available on site is a stop on the AC Transit 96 bus, which picks up and drops off once every 30 minutes, but does go to the 12th Street BART station.

Planners and housing advocates note, though, that more densely built housing and urban infill are better for the environment than continuing the old trend of constructing single-family homes in far afield suburbs. Infill developments tend to reduce vehicle miles traveled, and multi-unit buildings are much more energy efficient than single-family dwellings.

Peter Cohen, a former co-director of the Council of Community Housing Organizations, has devoted much of his career to researching solutions to urban sprawl.

“How housing affordability worked in America for decades, at least once suburbanization began in the 1920s or so, was you just keep going outward — land’s cheaper the farther you go out from the urban core,” he observes. “Now, we’ve decided from a larger ethical, environmental, and philosophical standpoint that that’s not really good or sustainable. [But] right now you’re dealing with a much smaller amount of land and a lot of contested interest in using that land.”

Climate Questions

Complicating the redevelopment of shoreline areas with an industrial or military history, however — places like Brooklyn Basin — are factors such as environmental contamination, seismic hazards, and, more recently, resilience to flooding.

Levy and Naomi Schiff of the Oakland Heritage Alliance, who have both been involved in preservation efforts in the city since the ‘80s, have a laundry list of sustainability concerns about Brooklyn Basin, from sea level rise to how well the developer cleaned up industrial waste from the 9th Avenue Terminal to potential liquefaction in the event of an earthquake.

“These are sensitive locations,” notes Brahinsky, the USF professor. “And the reason that they haven’t really been developed [yet] … is because of some difficult history, whether it is an environmental injustice in terms of air quality or something else.”

Left: The Jan. 3 king tide floods a street outside the Portobello Condominiums, which neighbor Brooklyn Basin. Right: A flooded parking lot next to Estuary Park during the king tide. Photos: Courtesy of Naomi Schiff]

This particular project is facing two categories of environmental concerns: old and new. The old, including seismic threats to the muddy shoreline soil and toxic waste left behind by industrial activity, were addressed by remediation requirements for the developer instituted by the city more than 15 years ago.

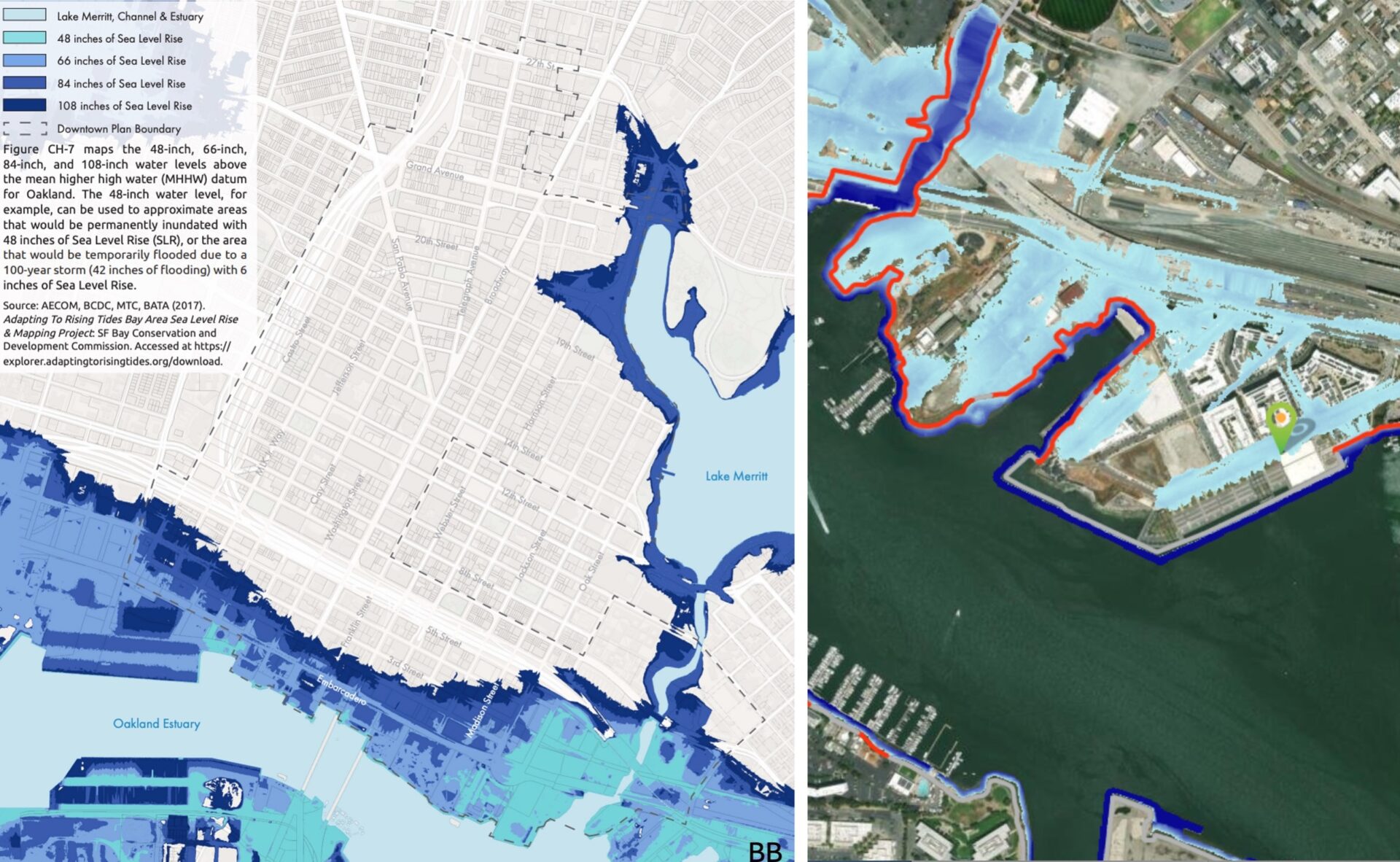

Levy and Schiff note, though, that sea level rise wasn’t on the public’s radar nearly as much when Oakland completed its first environmental impact report on the project in 2005. In fact, that 955-page document only mentions sea level rise in a brief section on potential flooding, where the city identifies the threat to Brooklyn Basin as minimal because it was not in the 100-year or 500-year FEMA floodplain established in 1982.

The 2024 Downtown Oakland Specific Plan, however, shows the entire waterfront, including the western edge of Brooklyn Basin, as at risk of inundation from sea level rise in the decades to come. One resident of a condo near Brooklyn Basin’s Estuary Park has seen water creeping onto the property as recently as a Jan. 3 king tide.

As I survey the site this month, I notice that out by another apartment building close to the water, and along other as-yet undeveloped waterfront areas, sand and dirt are stacked up and covered by tarps and sandbags along the water, presumably to protect the shoreline. Schiff and Levy wonder if this spot might eventually need a redeveloped marsh as a buffer, or perhaps a seawall.

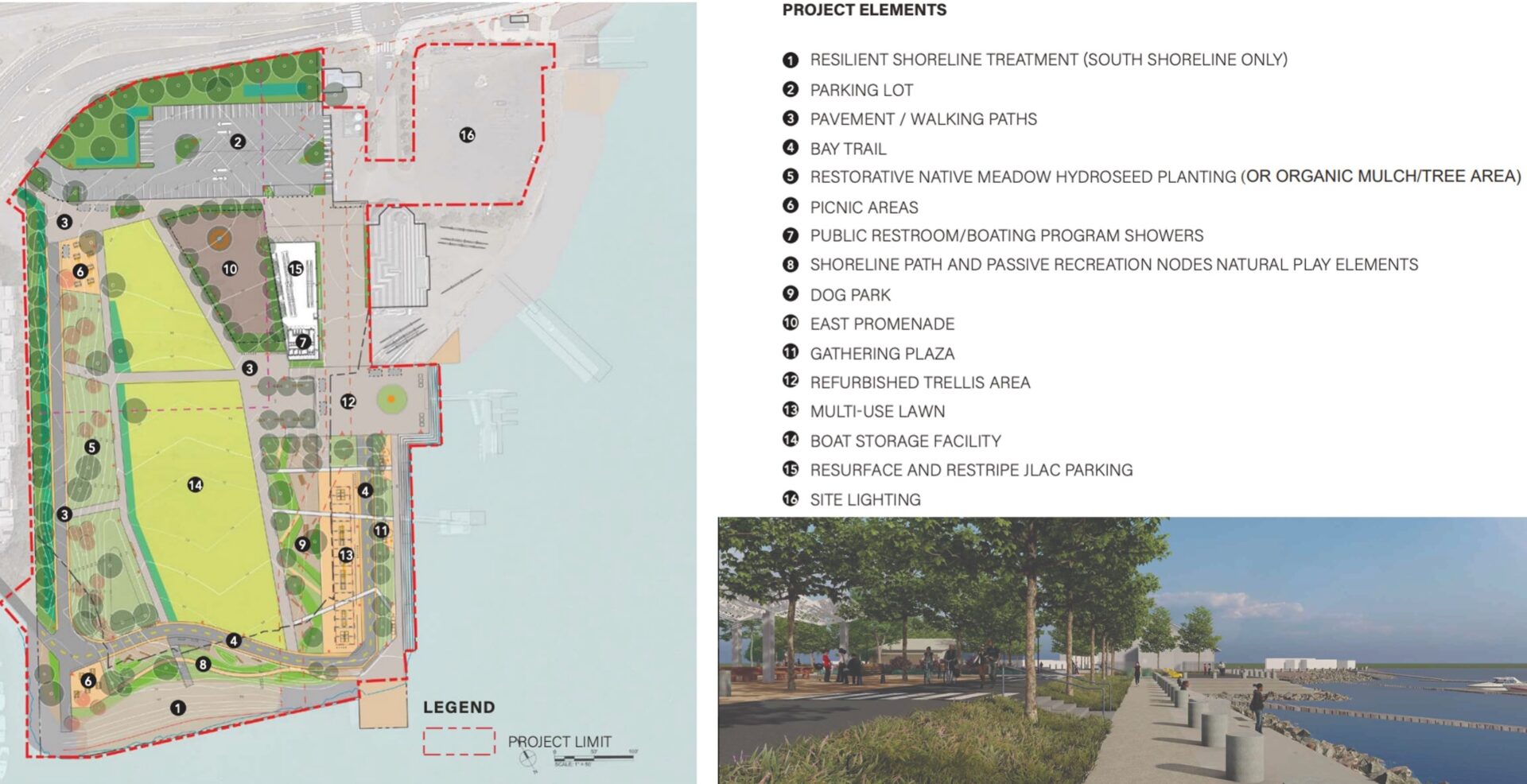

The western side of Brooklyn Basin may fare better, in terms of future flood risk, because of sea level rise mitigation strategies under consideration for a renovation of the 7-acre Estuary Park. The park’s expansion plan includes a California Environmental Quality Act checklist that notes that “the south shoreline will be reconstructed as a sand/gravel pocket beach and upland transitional zone, providing a resilient shoreline and new recreational areas” reinforced “with riprap shore retention and engineered rock revetments.”

Hoping to learn more about how Brooklyn Basin ultimately addressed the old environmental concerns, KneeDeep reviewed project approval documents from the late 2000s and contacted the city and developers.

The original EIR did require a geotechnical study and soil improvements to prevent possible liquefaction (when unstable or muddy soil liquifies in an earthquake, causing buildings above it to slide or crumble). Jean Walsh, a spokesperson for the City of Oakland, also reports that the Department of Toxic Substances Control approved a remedial action plan with specific requirements for the removal of industrial waste before construction could begin, a plan that was ultimately carried out with regulatory oversight.

Meanwhile, Lyn Hikida, VP of corporate communications and public affairs for MidPen, says the affordable housing parcel grades “were raised above the applicable floodplain elevations, and soil stabilization was achieved through the installation of 80- to 100-foot-deep reinforced concrete piles driven into competent underlying soils, providing structural support and mitigating the potential impacts of liquefaction, seismic activity and sea-level rise.”

Housing for Whom?

Beyond Brooklyn Basin, housing experts say they’re happy to see regional agencies adopt a vision for future growth with the PDA model. But they also worry that there is still not enough attention to affordability for low- and middle-income households.

“To me, the question when we’re talking about housing is housing for whom? Who are we housing, and is there a balance?” questions Fernando Marti, an architect and housing activist.

“When you ask about these PDAs, they’re PDAs that, absent an affordable housing policy, absent subsidy, basically create housing for wealthy folks, which is fine, but then what happens to the poor folks?” he says.

Despite California’s new laws aimed at building more housing, there’s no statewide mandate for a minimum number of units in a development to be allocated to people making below median income. Without that, Marti notes, “what we’re creating is long commutes from Tracy and long commutes from Antioch” for people who can’t afford to live closer to where they work.

He also stresses that there’s a fundamental disconnect between how much affordable housing the state and the Bay Area need and the percentage of new homes and apartments allocated to low- and middle-income people.

Every eight years, state officials publish a Regional Housing Needs Assessment. For the period from 2022 through 2030, they estimated that the Bay Area will need to build 441,176 new housing units. Of those, they said in a letter to ABAG, about 57% should go to people with low to moderate incomes, including 26% for very low-income households (making 50% or less of the area median income) alone.

An affordable housing development at Brooklyn Basin. Photo: Duncan Agnew

Most cities have some kind of inclusionary housing ordinance requiring just 10% or 15% of the units in a development to be below market rate. And in many cases, developers can also pay some kind of in-lieu fee to an affordable housing fund to skip over those requirements. When Brooklyn Basin’s developer came back to the City of Oakland looking to add another 600 units to the project’s original 3,100-unit total, for instance, it agreed to pay $9 million to the city’s affordable housing fund instead of making a percentage of those units affordable.

What’s often missing — as Marti, Cohen, and others note — is the political will and money for a city or region to demand that new developments actually match the income spectrum of the population.

“Cities that have a social housing program, whether they’re lefty cities like Vienna or more conservative cities like Singapore, they understand that [only] about 40%, maybe a little more, of jobs are going to be jobs that afford people market rate [housing]” Marti says. “And of course, we’re not doing anything at all [about that].”

Another problem Cohen sees is a lack of nuance in housing discussions, such as acknowledging negative consequences on surrounding communities. According to him, “anything that raises a question about new development” — be it affordability, toxic waste, gentrification, or public demands of developers — is labeled as anti-housing. “There’s no third place to be.”

For his part, Shorett of MTC/ABAG agrees that policymakers need to use the tools at their disposal to reap public resources and affordability from housing projects. Some strategies might include negotiating public benefits deals tied to a development, tax credits for affordable housing, changes to the state code to encourage smaller-scale multifamily buildings, or the creation of some kind of regional housing slush fund that cities can pool together for the collective good.

“[In the Bay Area] it’s very challenging for younger people to have long-term housing stability, much less be able to buy a home,” he says. “I think we benefit from thinking about what the other possibilities are that we could add to our policy toolbox. There is a very valid discussion to be had around inclusionary policies directed at ensuring there’s a benefit and some balance when you have a market-rate housing project.”

Back to the Basin

On a recent visit to the Brooklyn Basin site, the scene appeared to be very much still in flux. Township Commons park, next to the miniature version of the 9th Avenue Terminal that remains, has some benches, rows of trees, and grassy areas where people were letting their dogs play or pushing strollers. The 96 bus pulled up to a corner between several of the new buildings, and a group of people hopped on.

The 96 bus pulls up in front of the Vista Estero affordable housing development. Photos: Duncan Agnew

MidPen reports that nearly 100% of its 465 affordable units are occupied, with a few in the process of being filled, and the wait list for its buildings is closed. Signature Development did not respond to several inquiries from KneeDeep about the occupancy rate of its own housing on site, its planning for climate hazards, and its long-term vision for installing more retail space and parkland in the neighborhood.

The community feels lived in, but there’s an incompleteness to it. Several lots remain fenced off, vacant, and muddy. There’s some old, wrecked boats in the estuary. Most of all, the basin lacks shops and restaurants, other than a coffee shop, a Filipino street food spot, and a German beer garden. The terminal that Levy once dreamed of turning into its own Ferry Building has one restaurant, some plaques about the history of Brooklyn Basin, and several retail spaces sitting empty.

But there’s plenty of hope for the future. More housing, Estuary Park’s renovation, a new dock for water taxis, and more parkland are all in the works.

As for the PDA idea as a whole, “I have to throw a bone at it and say it’s a decent try,” Cohen admits, acknowledging that a planning vision for transit-oriented development is a good thing. “I just think it falls short of where it could be, and of the level of sophistication that could happen. So I’m maybe a cautious advocate that this is going in the right direction, and it needs a lot more nuance and a lot more risk management of potential displacement and gentrification.”