Composting as a Ritual for Renewal

A farm high in the Contra Costa County hills helps folks learn from the land and connect with nature.

Along a south-facing slope in the El Sobrante watershed, wisps of smoke waft from a long bundle of dried sage in the hands of Gabby Abebe, an organizer with Sankofa Roots. Sankofa is a land-based learning and healing organization that connects Black, Indigenous, and queer communities with nature. Their offerings include emergency preparedness training, skill shares, workshops, campouts, and volunteer days.

Today the Sankofa team is hosting a soil and compost volunteer day at Soul Flower Farm. One by one, Gabby waves sage over each volunteer. Then Maya Blow, Soul Flower Farm’s founder, invites us into a large wooden gazebo. A few black phoebes and house finches welcome us with sweet melodies as rays of sun dapple through the skylight overhead. We circle up on colorful rugs laid over wood chips and introduce ourselves by sharing our names, our pronouns, and why we’re here.

“I’m here because my ancestors brought me here. At least that’s what I believe,” says Jeremiah Haskins, a Rudy Lozito Fellow. The fellowship is based at Urban Tilth, an organization that trains residents of Richmond to build more sustainable food systems.

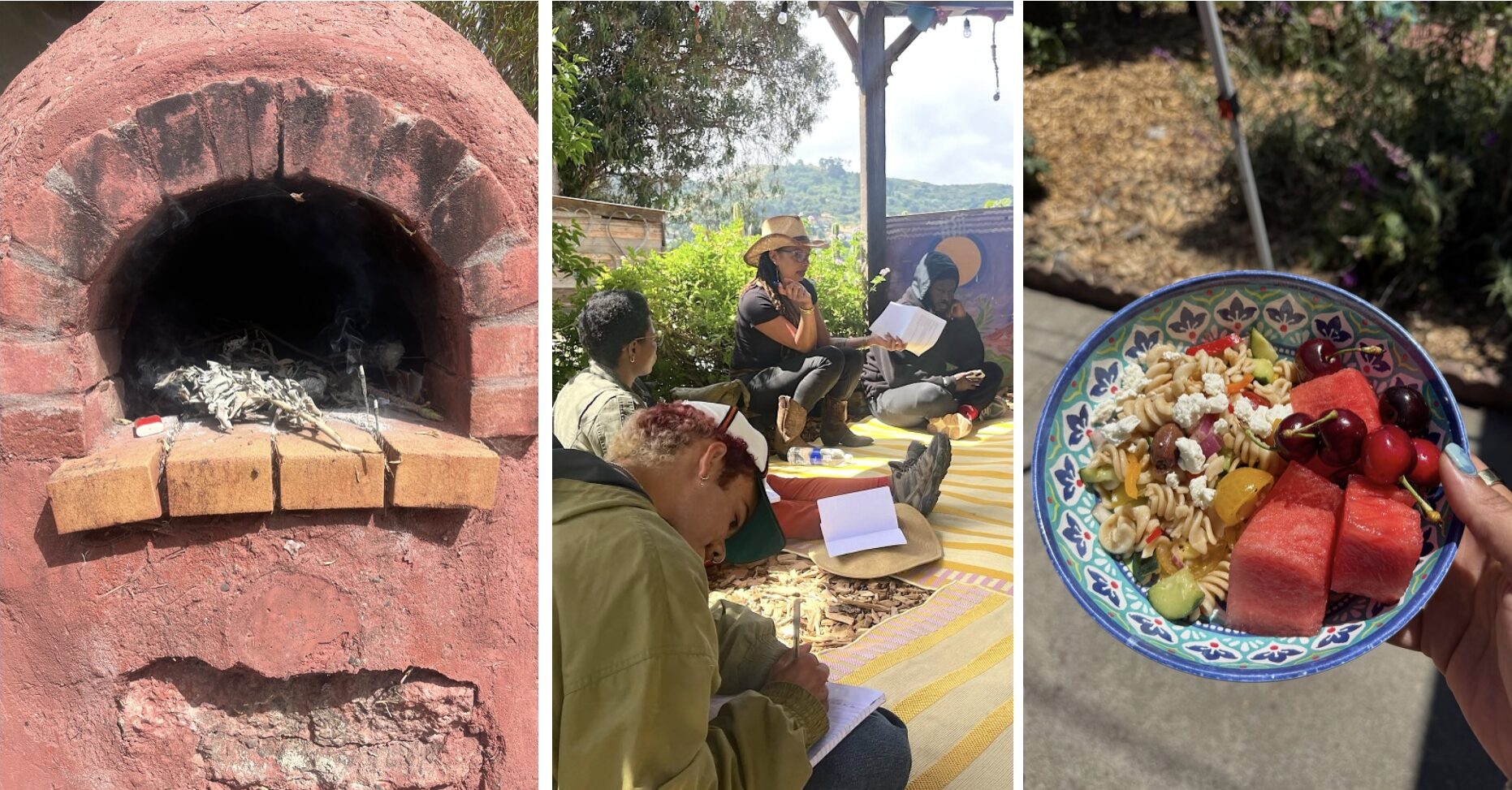

Burning sage, gathering for a lesson, lunch. Photos: Jordan Burns & Otito Obi

Daniela Tabora, who runs the Rudy Lozito Fellowship, explains how today fits into the larger context of their curriculum. “This compost day aligned beautifully with our program’s seasonal rhythm. We’re currently entering month three, where our focus shifts to a deeper dive into soil. [In] our first two months, we build the foundation — group agreements, tool safety, seed starting and saving, greenhouse care, food-safe harvesting, and core farm tasks. Now we’re getting into soil texture, composition, carbon sequestration, nutrient testing, and remediation.”

Other volunteers share that they’re excited to learn more about soil and composting so they can better tend to their gardens at home. Blow thanks us all for being here and brings us on a journey through the history of Soul Flower Farm. She and her family began the farm by focusing on annual food and meat production. “It started as an experiment to see how much we could produce of what we consume,” she explains. This was no easy task, given that Blow and her partner were raising two teenage boys with large appetites. “Within a year, 90% of our dinner plate came from the farm.”

Building a base for the compost pile. Photo: Otito Obi

Blow highlights the importance of listening to the land’s needs and stewarding the land accordingly. Originally, when they first moved onto the farm, they were intent on double digging. The double digging method consists of loosening two layers of soil and then enriching both layers with organic matter and putting them back in place.

They quickly realized their plan wasn’t going to work because of the bouncy texture of the clay rich soil on the land. “We would dig and dig and it was almost like the soil would just laugh at our shovels,” she says. They ended up turning to sheet mulching at first, so they could more effectively work with the clay instead of against it.

After taking us through Soul Flower’s history, Blow gives us a lesson on soil and composting. She begins by differentiating soil from dirt. “Dirt is dead. Dirt has minerals and is devoid of life… soil is loose surface material that provides structure for life on earth. Soil is alive.” She goes on to explain the basics of composting. The process involves recycling organic matter (such as leaves, food scraps, and waste) into fertilizer for soil and plants. She informs us that hot compost piles are high maintenance and can be ready in as little as 18 days. In contrast, cold compost piles require minimal effort and can take up to a year breaking down before they’re ready for the soil. She then walks us through how to make compost teas and how to use worms to create rich compost in vermiculture.

The final composting method Blow outlines is the S.P.I.C.E method, which stands for static, pile, inoculated, extension. S.P.I.C.E is both effective and convenient — instead of routinely turning the soil to aerate it, the compost pile is infused with microbes, then covered and left to decompose. She explains how greens and browns improve the piles: “Greens can include plants, chicken scraps, and anything fresh. Greens keep moisture in. Browns include drier material like straw and mulch. They provide carbon.”

Donté Clark, a Rudy Lozito fellow, pours nutrient supplements into the S.P.I.C.E. pile. Photo: Otito Obi

Maya Blow closes the lesson by emphasizing her firm belief that “anything biodegradable can be composted.” She acknowledges that not everyone follows that philosophy. Some people prefer to avoid animal products for fear of maggots. Others avoid urine for fear of acidity. “But urine is a great activator; it’s like kombucha for the soil!” she exclaims. She also points out that blood is particularly enriching because it infuses soil with healthy minerals like potassium, calcium, magnesium, copper, and zinc.

After the lesson, we do some group stretching to limber up for the labor ahead. Then we trek down a mulched hill with arms full of cardboard boxes, ready to put the S.P.I.C.E method into practice. Afrobeat music keeps us company while we work. We break down boxes and gather tree branches, using them as a base for the compost pile. A small group of us heads back up the hill to gather some greens. In the garden next to the chicken coop, we uproot calendula that’s gone to seed, leaving behind lavender, tomatoes, fava beans, and daisies. Another group heads further downhill to uproot wild poppies and grass, leaving behind sweet corn and milk thistle. The layer of greens goes down and we get to work with more browns.

Volunteers (Gabby and Disha) carry a layer of green calendula. Photo: Otito Obi

About an hour later, we have lunch on a spacious wooden deck. Daniela Tabora shares an incredible pasta salad, fresh watermelon, oranges, pretzels, chocolate, and hummus with the group. After lunch, we drag barrels of hay down the hill on large blue tarps and add them to the compost. We take turns sprinkling nutrient supplements onto the compost pile to help support the soil. Some ingredients in the supplements include seabird guano, alfalfa, basalt, kelp meal, neem seed meal, shrimp meal, Epsom salt, and dolomite. A volunteer sprays water onto each layer of green and each layer of brown. We continue on like this, layer by layer until the pile is about four feet high. We pause the music and Blow invites us into a ritual to bless the soil. We lay our hands over the compost pile and we each speak out words of good will for all the living beings the soil will nurture and nourish. We share intentions for rebirth, interdependence, land liberation, abundance, joy, and resilience.

We spread blue tarps over the compost and weigh them down with bricks. In six months’ time the compost pile will be ready to enrich the ground. This practice is a reminder of the beauty and growth that’s possible through cycles of decay.

Daniela Tabora shifts hay. Photo: Otito Obi

After the volunteer day, I spoke with Jamani Ashe, the founder of Sankofa Roots. I asked them why it feels particularly important to build skills and knowledge around soil and composting in the communities that Sankofa serves.

“Soil is memory. Composting is ceremony,” they replied. “For Black, Indigenous, and queer communities, working with soil is not just practical — it’s deeply spiritual. It invites us to remember who we are and how we belong. In a world that treats us as disposable, composting reminds us that nothing is wasted. Every loss, every struggle, every story can be transformed into nourishment. It’s a radical act of resistance and renewal — one that reclaims our relationship to land, body, and spirit.”

Top Photo: Learning about comfrey (l-r Jordan, Rubi, Maya). Photo: Otito Obi