Can Colgan Creek Do It All? Santa Rosa Reimagines Flood Control

A short history of stormwater design changes over six decades and how they affected one Santa Rosa Creek.

Colgan Creek was once just a creek. Like most creeks, it would occasionally overtop its banks and spill out over the floodplain. The City of Santa Rosa, like most cities with most creeks, did not want it to flood. A functioning floodplain is good for many things, but not for building upon.

In the late 1970s, Santa Rosa converted lower Colgan Creek from a natural waterway into an earthen flood-control channel. Its path was moved, in some cases hundreds of feet; its bends straightened; and its banks denuded, all so that water could flow more freely downstream to the Laguna de Santa Rosa wetlands. Riprap was added here and there to reinforce the new alignment and reduce erosion. The creek’s ecological function became secondary to its flood-fighting role.

Now a 1.3-mile stretch of Colgan is being transformed again. And its updated design – though not explicitly informed by projected climate conditions – may provide a model for an ecologically sound, flood-resistant urban creek in California for the 21st century. It slows, sinks, and filters runoff as much as possible and provides habitat and aesthetic benefits at the street level, all within an expanded, higher-capacity envelope.

Riparian creek corridor (tree tops) after the first phase of restoration work in 2014 . Photo: City of Santa Rosa

While last winter’s storms are behind us and an extended dry season lies ahead, the state is staring down a long-term future likely to include fewer but increasingly severe storms due to increases in the water-holding capacity of our warming atmosphere.

“Climate change promises to make managing California’s water even more challenging,” wrote the authors of a 2020 report out of the University of California, Los Angeles. “However, it’s unlikely the biggest change will be in the overall amount of precipitation the state gets. Instead, the character of precipitation will probably change, with more intense atmospheric rivers and longer dry spells between them.”

This evolving precipitation regime is likely to expose new weaknesses in traditional flood channels and aging stormwater infrastructure throughout the state, says Emily Corwin, a water resources engineer and director of strategic initiatives at the San Francisco Estuary Institute.

“There’s the stormwater infrastructure you can see above the ground, and then there’s a whole series of pipes and pumps and drain inlets that we can’t see so much. And everything, the whole integrated system, is going to need to be adapted to accommodate climate change.”

Fast Vs. Slow Flood Design

Throughout the mid-20th century, cities and towns across California did to their creeks much the same as Santa Rosa did to Colgan: restructure them into straight, bare, high-capacity channels to shuttle rainwater away from buildings and streets, to anywhere else, as quickly and seamlessly as possible.

The Los Angeles River, famously encased in concrete following a major flood in 1938, became the poster child for modern flood control as the practice remained standard from the post-war building boom through the 1970s.

And from that perspective, the first transformation of Colgan Creek was a success. Flooding became relatively rare, and isolated. Rainwater rushed off to the Laguna de Santa Rosa as intended.

Restored section of Colgan Creek. Photo: Nate Seltenrich

But its new design also created two new problems. First, testing showed that water quality in the channel was poor across a variety of parameters. And second, all that bad water was rushing downstream to the Laguna, a sensitive (though heavily altered) freshwater wetland complex inundated every winter with stormwater from numerous creeks in Santa Rosa and Rohnert Park.

Reduced flood risk upstream in urban areas meant increased risk downstream in both the Laguna and the lower Russian River into which it spills. This put communities like Sebastopol and Guerneville at greater risk, planted as they are near the end of a long funnel. Channelized creeks like Colgan were merely passing the buck – and potentially impairing water quality miles downstream.

In the meantime, more ecological approaches to managing stormwater in urban settings began to develop: vegetated detention basins, bioswales, permeable pavement, and the like. By the 2000s, a whole new paradigm had emerged that aimed to “slow and sink” urban runoff to help filter out pollution, boost habitat values, replenish groundwater and depleted aquifers, and reduce peak flows into creeks and channels.

Bulb-outs collect street runoff in Santa Rosa. Photos: Nate Seltenrich

Variably referred to as “green stormwater infrastructure” and “low-impact development,” this newer suite of stormwater control measures offers numerous advantages relative to traditional flood-control channels and has been embraced by many California cities. Yet with its generally smaller scale and slower function as a filter, not a chute, green stormwater infrastructure is designed to handle routine runoff and rainfall, not torrential downpours.

“Almost all green infrastructure stormwater control measures rely on infiltration for volume control and pollutant load reductions,” says Randy Neprash, a stormwater regulatory specialist and consultant. “Infiltration is a slow process. Rain in intense storms comes quickly. Almost all green infrastructure [measures] have relatively small storage volumes. Thus, the rain comes fast, fills up the storage in just a few minutes, and most of the rain is bypassed around it.”

Mimicking a Natural Creek

The reimagined Colgan Creek may capture the best of both worlds. Taking a cue from the philosophy and recent lessons of green stormwater infrastructure and low-impact development, the project restores some of the creek’s original layout and function while simultaneously expanding its footprint. What’s old is new again.

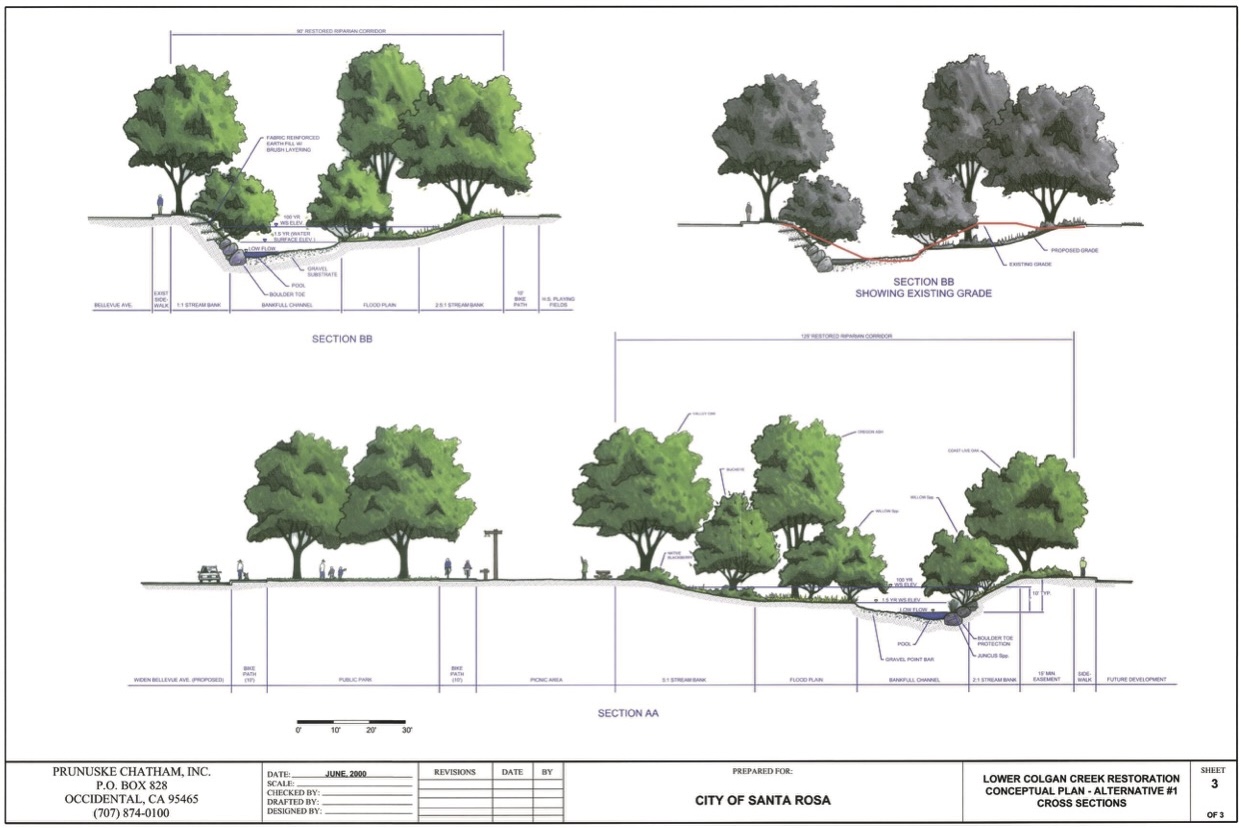

“It’s really taking an earthen flood-control channel and converting it into a more natural creek, and upsizing the capacity,” says Steve Brady, a senior environmental specialist with the City of Santa Rosa who has been involved with the project since its earliest days in 2001. “We’re installing all different types of habitat and plantings and log structures, while also greatly enlarging the channel cross-sectional area to carry more water and slow it down and infiltrate it into floodplain areas.”

The project’s first phase, completed in 2014, restored a 2,000-foot stretch of the channel, (originally sized to carry a 25-year flood with a 4% chance of happening in any one year) into a larger, more ecologically sound creek (sized for a 100-year flood with a 1% chance of happening each year).

Phase two, completed in 2022, restored another 1,900 linear feet with more riffles, large woody-debris habitat structures, boulder step pools, native riparian plantings, and enlarged floodplains that would increase groundwater infiltration while protecting nearby homes, schools, and businesses from flooding.

Phase three, starting in June and slated for completion next spring, will add another 2,500 feet and bring the total restored stretch up to 1.3 miles. “This is a significant restoration project for us,” Brady says. “It’s the largest one that we’ve ever attempted.”

More importantly, the project embodies an even bigger idea that could hold sway well beyond its banks: melding traditional high-capacity flood-control channels with key principles of green stormwater infrastructure and low-impact development.

Flex at the Edge

In some ways, the Colgan Creek project recalls the burgeoning “living shorelines” movement, which seeks to fortify and stabilize vulnerable coastal shorelines against climate-change-driven sea level rise and storm surge using natural materials, resilient designs, and built-in habitat instead of the bare, impervious, “hard” bulkheads and seawalls of the 20th century.

Yet as excited as Santa Rosa is about the new Colgan Creek, the approach it’s taking is not likely to be replicated anywhere else in the city or the broader Laguna de Santa Rosa watershed. The work was only possible because this stretch of the creek had yet to be hemmed in by development.

California Conservation Corps plants Phase Two of the Colgan Creek project. Photo: City of Santa Rosa

The city received grant funds from the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District, as well as the California Department of Water Resources, Wildlife Conservation Board, and Natural Resources Agency, to acquire three privately held yet undeveloped parcels adjacent to the creek so that it could expand and realign its footprint while maintaining a ribbon of functioning floodplain and even add new multi-use paths along its banks.

The vast majority of other flood-control channels constructed in the mid-20th century are now far more constrained by development. Modifying them again will require creative approaches and solutions.

That’s certainly the case at the notoriously unnatural LA River, currently slated for a renewal of its own. Much like at Colgan, though on a far grander scale, plans are underway through the County of Los Angeles’ LA River Master Plan to boost biodiversity, improve water quality, and increase flood capacity.

To accomplish this, the county plans to buy back and reclaim parcels in the historic floodplain; add native plants and habitat corridors in and along the river; reduce peak flood flows into the river with upstream storage and groundwater recharge facilities; and modify the channel itself through widening, terracing, and other approaches.

Similar shifts in flood management approaches are also happening in the Bay Area near the mouth of Walnut Creek, formerly channelized, dredged, and wedged between levees by the US Army Corps of Engineers in the 1960s and recently reconnected with its historic floodplain marsh; and along the flood-prone Napa River, where the county, the city and vineyard owners all did their part to give the river much more room to spread in the wet season.

Perhaps Colgan Creek, the LA River, and others like them can be thought of as representing a new form of stormwater infrastructure in California that combines the key benefits of two earlier generations into a fresh package: innovative yet familiar, natural yet engineered. We might call them “living” or “green” flood channels, perhaps, or high-capacity green stormwater infrastructure. No matter the name, it’s only a matter of time before next winter’s atmospheric rivers put them to the test.

KneeDeep is looking for examples of stormwater and flood control designs that incorporate thinking about high intensity rapid rainfall. If you have an example email editor.