Without Transit Rescue Measure, Bay Area Faces Major Climate Setback

Thousands more cars on the road. Millions more gallons of gas guzzled. A greater than 70% increase in traffic on the Bay Bridge. Up to 10 more hours spent commuting from the East Bay to San Francisco every week. Entire rail lines shut down. And no free or subsidized public transit rides for youth, low-income families and seniors.

That’s the reality heading to the Bay Area like a freight train in the 2027 fiscal year, unless enough voters step up to pass a ballot measure funding public transit in November 2026. The proposed ballot measure, authorized by SB63, passed the state assembly and senate in September and is expected to be signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom soon.

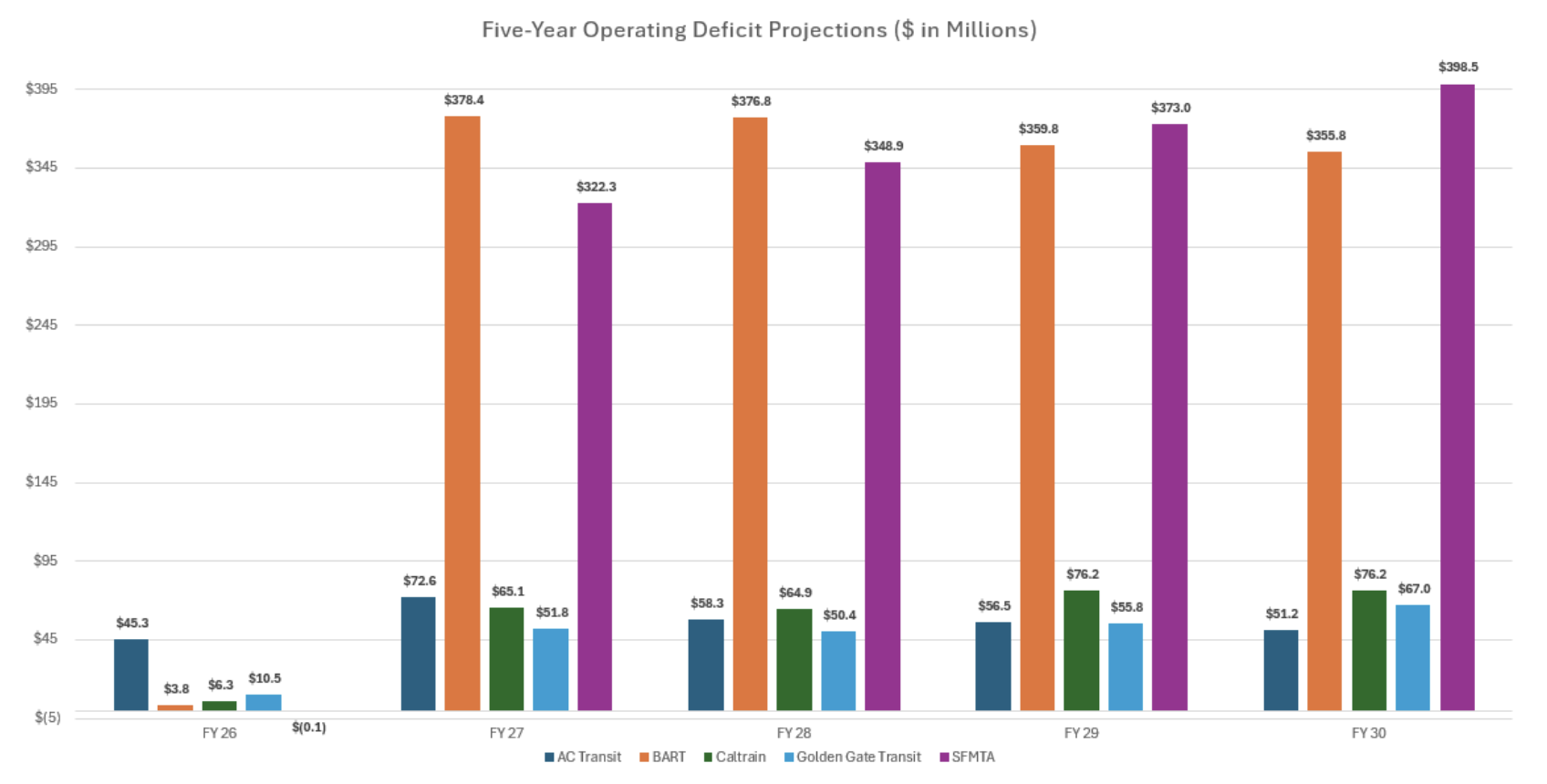

The measure will ask voters in Alameda, Contra Costa, San Mateo, and Santa Clara counties to support a half-cent sales tax, and San Francisco County for a full cent sales tax, to fund operations and improvements to BART, Caltrain, Muni, and AC Transit for the next 14 years. Without this bailout, those agencies are facing a combined budget shortfall of more than $800 million starting in 2027, largely due to remote work cutting fare revenues in half from pre-pandemic levels. BART, for example, covered more than 70% of its annual operating budget with fares before the pandemic. In 2024, that was down to 29%.

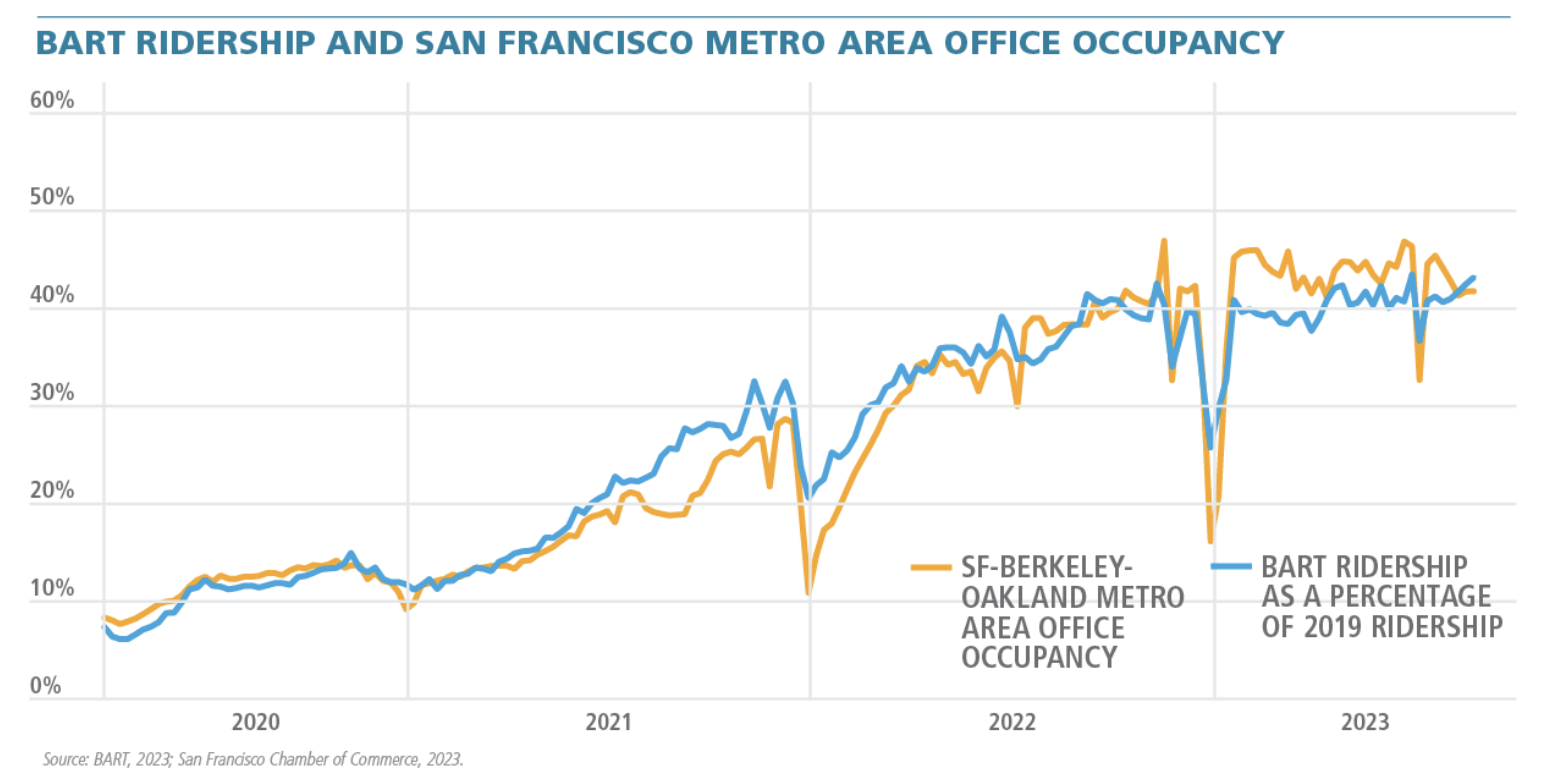

As Rebecca Long, director of legislation and public affairs for the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, put it, most people in the Bay Area now work from home at least twice a week, a crippling blow to transit agencies that used to get two rides a day, five days a week from commuters. And that doesn’t even account for all the people who turned to car travel during the pandemic and haven’t looked back.

The SB63 ballot measure has drastic implications for the region’s goals for the economy, climate resilience, and equity. Long-term local and regional plans, according to experts, depend on the existence of a robust and connected public transit system to bring workers to business centers, keep cars off the road, and give low-income communities access to the wider Bay Area.

“There’s a scenario where it’s really a question of whether it would make any sense to operate anymore, and this would be completely devastating to the region’s climate goals,” Long says of the fiscal cliff that transit agencies are facing.

“Our long-range planning, and all of our population growth and housing planning and housing growth, is really focused on transit-oriented development and putting more affordable housing near transit. Without that reliable BART system, and other systems, to support that housing, that entire model of how we’re going to grow kind of goes out the window.”

For example, Newsom just earlier this month signed SB79 into law, which is designed to streamline the development of housing near BART and Caltrain stations.

Devil in the Details

According to polling conducted by MTC in early 2025, about 55% of voters support some kind of sales tax to fund public transit operations. That number rises, however, when voters are simply asked if they value bus and rail transit. As Long says, even car commuters “don’t want all those BART users converting to driving and clogging up the freeway.”

Perhaps the trickiest part of the ballot measure, though, is the threshold needed to pass it. SB63 gives MTC the power to put the question on the November 2026 ballot, but that route would require a yes from two-thirds of voters.

But another option is more attractive to transit riders and advocates. If a “citizens’ initiative” — without help from any government agencies, including MTC — gathers at least 200,000 signatures by mid-2026 in support of the ballot measure, it would only need a simple majority (anything over 50%) to pass.

Caltrain gives Peninsula residents an option to ride the rails instead of driving the Peninsula’s crowded freeways. Photo: Joey Kotfica, MTC

Nonprofits like SPUR, San Francisco Transit Riders, Transbay Coalition, and Friends of Caltrain report that they plan to coordinate signature campaigns starting in January, when the window for petition circulation will officially begin. If the signature effort ultimately fails, MTC has until August 2026 to put the measure on the ballot directly.

“The numbers have been fairly consistent in showing that Bay Area voters place a really high value on transit — they’re concerned about the fiscal state of transit, they want transit to improve. The polling has also suggested that if a measure were to go on the ballot tomorrow, somewhere between 50 and 60% of voters would support it,” says Sebastian Petty, SPUR’s senior transportation policy advisor.

“That’s not ideal for where numbers could be, certainly not if you’re trying to get to two-thirds, but it does suggest a pretty viable path via citizens’ initiative. I would suspect there will be a major effort to go that direction.”

According to Adina Levin of Friends of Caltrain, nonprofits and community organizations are likely to launch a “community field” effort to back a citizens’ initiative for the SB63 ballot measure starting in early 2026. Levin referenced the November 2020 Proposition RR to fund Caltrain with a 0.125% sales tax as a model for how these groups are approaching SB63. That measure ultimately passed with 69% support among Bay Area voters.

In San Francisco, a companion measure proposed by Mayor Daniel Lurie also calls for a parcel tax increase to round out Muni’s funding gap, which the agency is estimating at $322 million for 2027. San Francisco Transit Riders’ Muni Now, Muni Forever campaign is backing that effort.

Fixed Costs and Political Will

According to BART’s Role in the Region report, press releases from Caltrain and interviews with Long and Petty, rail transit is especially vulnerable to budget shortfalls because of its high fixed costs.

“Regardless of whether BART runs 100 trains or two trains, they still have to keep stations open, they still have to maintain infrastructure, they still have to maintain the signal systems on the train,” Petty says. “So if they start having to cut back service, they get into a situation where you have to cut a huge amount of service to just save a little bit of money.”

That’s why, in presentations on the coming fiscal cliff, BART says it would have to cut up to 85% of its service to save just 40% of its budget.

“There’s a real risk that you start to go into this kind of death spiral pattern,” Petty adds, “where transit cuts service, transit loses riders, transit has less money, transit has to cut service, transit loses even more riders.”

Mirroring the Bay Area’s office vacancy rate, BART’s ridership is stuck at around 40% of pre-pandemic levels. Source: BART

And, despite a sales tax being regressive, meaning that everyone pays the same amount regardless of income, both Petty and Long describe the SB63 path as the only option to fund transit that likely won’t face funded opposition.

All Republicans in the state legislature either voted against SB63 or did not vote on it at all, and other opponents thus far include statewide business and anti-tax groups. In a policy paper on the bill, SPUR reports that “there’s currently little evidence to suggest that other revenue options, such as a parcel or payroll tax, would be acceptable to the legislature, appealing to voters, and able to withstand a funded opposition campaign.”

Business groups would likely be an obstacle to any new tax tied to employment or real estate, for example. A sales tax is borne by individual consumers instead, and even though it taxes everyone equally, in this case it would support something in transit that disproportionately helps low-income communities, Petty notes.

“Politically, there was not a path forward that would generate consensus from the business community and labor advocates that was anything other than a sales tax,” Long says. “It’s a really hard challenge to persuade voters to tax themselves, especially now, where one of their biggest concerns is affordability. So if you have funded opposition to a funding source, you’re very likely to fail.”

Climate Over Cars

If BART were to shut down entirely, according to its own estimates, cars in the Bay Area would burn 35,000 to 70,000 more gallons of gas per day.

“Thirty-eight percent of California’s greenhouse gas emissions come from transportation, and driving emits 42 times more greenhouse gases per mile than BART,” the agency says in its Role in the Region report.

BART’s Civic Center station. Photo: Joey Kotfica, MTC

Perhaps even more importantly, though, failing to invest in the future of transit could spell the end of the region as we know it, Long warns. Developers would no longer have any incentive to build near transit, leading to less density, even more reliance on single-family homes and cars, and a reversion back to urban sprawl.

Commenting on the climate risks posed by traditional car transit, Santa Clara County Supervisor Margaret Abe-Koga, who also serves on MTC, notes that the Bay Area Air District tracked a 38% decrease in carbon emissions during pandemic shelter-in-place orders. But “since then, more cars are on the road and reductions in service would only reduce air quality.”

The SB63 ballot measure, however, “allows cities to think strategically about future growth, integrating our housing and climate goals with the certainty that we will have reliable transit to support those ambitions,” Abe-Koga says. “It empowers our local agencies to focus on long-term strategies that keep our region competitive and sustainable.”

Top Photo Muni Metro station in San Francisco: Joey Kotfica, MTC