A Rare Plant Tough Enough to Save the Future Bayshore

Rare plants are often considered fragile. After all, there’s a reason they aren’t common … right? Yet along San Francisco Bay shorelines, one species not only can be surprisingly robust — it also has the potential to help the region adapt to sea level rise.

The last wild populations of California sea-blite in the Bay Area died out in the 1960s as its shoreline habitat was lost to development — leaving this nondescript shrub locally forgotten by all but the most devoted botanists. Surviving in only one location, 200 miles south in Morro Bay, it’s listed as federally endangered.

“This species is in jeopardy, but it is not a meek, mild, and fragile plant,” says ecologist Peter Baye, who has been incorporating sea-blite into restoration projects for more than 20 years in a reintroduction campaign that’s gradually gaining momentum. “These are robust ecosystem engineers. They just need a little help getting back to where they can colonize.”

Sea-blite survives amid storm wrack at Brunini Marsh at Blackie's Pasture in Marin County. Photo: Peter Baye

Unlike many rare plants, sea-blite can thrive in disturbed human environments, Baye notes. Preferring well-drained tidal shores with sandy or shell-based soils, it can grow among riprap and even on beaches, as well as on the banks adjacent to tidal mudflats, along with pickleweed and gum-plant. Baye has seen it routinely trampled by fishermen, or crushed under boats alongside docks, without suffering.

But bringing sea-blite back doesn’t just benefit the plant — it helps people, too. There aren’t many other native plants that thrive in this high marsh habitat; and none that grow in the same way as sea-blite: evergreen, spreading, and able to climb and withstand drought.

“Sea-blite has sort of a superpower in [restoration],” says Katharyn Boyer, interim director of San Francisco State’s Estuary & Ocean Science Center, who along with her students has been working with Baye to design and monitor multiple pilot projects reintroducing sea-blite to the Bay. “It won’t grow just anywhere, but we are learning what it likes. It can play a part in the multiple resiliency features that you might be adding to a restoration site.”

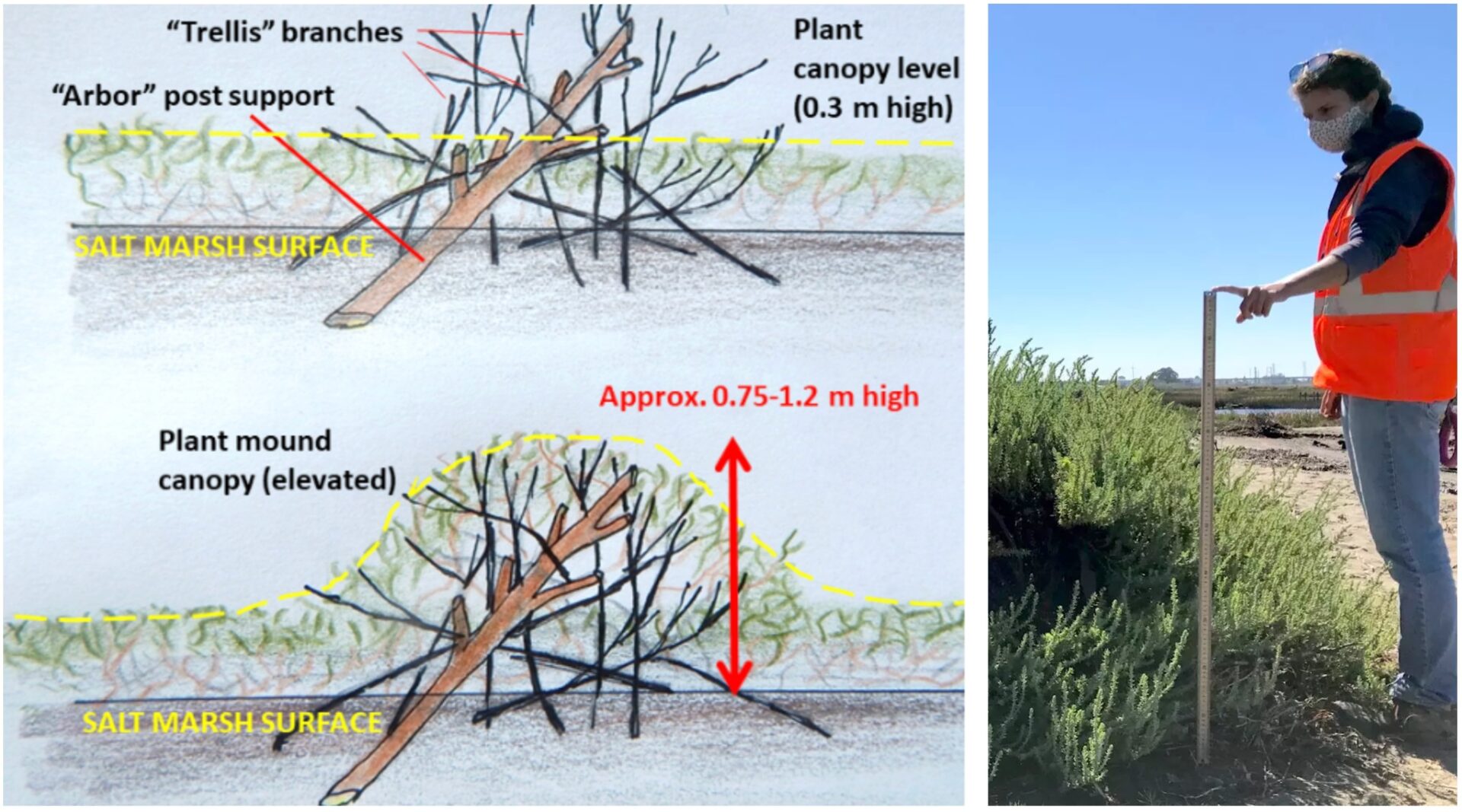

Sea-blite climbs up arbors of fallen branches placed by ecologists, creating high tide refuges for endangered marsh species. Diagram: Peter Baye; Photo: Melissa Patten

Once established, sea-blite can help protect shorelines and prevent flooding by reducing waves and buffering their impact. It can anchor beaches and even be coaxed to grow taller than most of its neighbors, serving as a refuge for birds and mammals during flooding.

Despite this, it’s not yet widely included in restoration planning beyond Boyer and Baye’s six pilot projects:

- Emeryville Crescent (Emeryville)

- Pier 94 (San Francisco)

- Heron’s Head Marsh (San Francisco)

- Greenwood Beach marsh (Blackie’s Pasture, Tiburon)

- Muzzi Marsh (Corte Madera)

- Giant Marsh (North Richmond)

“People hear us talk about it and they get excited,” Boyer says, “but it is still kind of under the radar.”

But the uptick in enthusiasm for constructing living shoreline projects may give sea-blite its chance to shine.

“They always were an edge species, and right now we’re building beaches and creating new edges,” Baye says. “There’s a big potential for artificial renovation of just the right backshore and outer marsh banks habitat, and this is a missing piece that could fit in it better than the other species we have left.”

Editor’s note: Sea-blite is one of the engineering plants, animals, and materials being featured in KneeDeep’s mini-series on the building blocks of climate adaptation. You can also read our features on beavers, baycrete, mass timber, and pervious concrete, or send us ideas for other materials to cover.