Alameda Flood Group Keeps Chin Up Despite Claw Backs

The region is reeling from the withdrawal of more than $350 million in grants promised between 2020 and 2023 under a federal program designed to make infrastructure and communities more resilient.

Sarah Atkinson grew up on Bay Farm Island in the City of Alameda, just west of Oakland International Airport.

Nestled on the Bay, the island is home to more than 13,000 people, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, and the San Francisco Bay Trail attracts runners and bikers to the neighborhood’s coastline.

“Bay Farm has this beautiful walking and biking path all the way around the edge that’s public,” Atkinson says. “A lot of people do use it — is it mostly used by the people on Bay Farm? I don’t know, versus other people in Alameda — but it is a pretty well used recreational area. I grew up biking along there as a kid.”

But flooding from sea level rise is a growing threat to Bay Farm. Significant portions of the island, the Bay Trail and the Oakland airport already lie in a 100-year floodplain designated by FEMA, meaning that they face a 1% chance of a 100-year flood occurring in any given year. The state is also projecting the sea level to rise by up to a foot by 2050, without accounting for these potential storms.

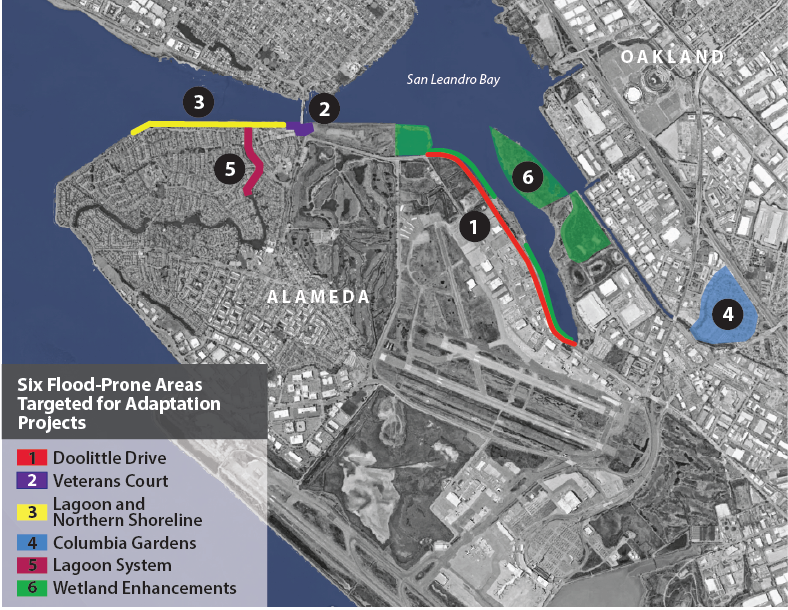

Three particular spots are already vulnerable to spillover from the Bay, according to Danielle Mieler, the City of Alameda’s sustainability and resilience manager. Those include Doolittle Drive next to the airport, Veterans Court and the lagoon outfall on the northern coastline of the island.

To tackle this issue, Mieler helped bring more than 30 partner organizations together on the Oakland Alameda Adaptation Committee. The committee applied for a massive $50 million grant last year from FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program for shoreline adaptation. Crucially, BRIC grants cover 90% of project costs in disaster resilience zones (like the Oakland airport) instead of the 75% typical for other FEMA grants, which would have been “a huge benefit to the whole community,” Mieler says.

The Trump administration had other plans, though. Shortly after the president’s inauguration, the federal government froze the BRIC program and started clawing back billions of dollars in funds previously allocated to climate resilience work across the country.

For Mieler and the rest of the adaptation committee, it was back to the drawing board, but they refused to let the project die. Since the spring, thanks to a previous congressional earmark, they’ve completed 30% of the design work on a project to safeguard the north side of Bay Farm from flooding and to protect the Bay Trail from erosion.

“It’s a loss of opportunity to provide benefit to our local communities that is unfortunate,” Mieler says of the BRIC grant loss. “But we have to find a way to move forward.”

Map of sea level rise adaptation projects for Alameda.

For Atkinson, who’s now the hazard resilience senior policy manager for SPUR, and other organizations like BayCAN, Alameda and Mieler are showing other cities and municipalities how to be resilient in the face of federal cuts.

Her tenacity has caught the attention of people like BayCAN’s Michael McCormick, who reflected on her response to the grant withdrawal by saying “You know what? That’s great that ‘no’ is not an answer she is willing to accept.”

“And she started making phone calls to everybody she knew that she could think through this challenge and this dynamic with.”

Bigger Bucks on the Brink

The Bay Conservation and Development Commission is estimating that the region will need about $96 billion for adaptation projects by 2050 to mitigate the effects of sea level rise and other environmental hazards caused by climate change, according to BCDC Director of Planning Jessica Fain. That’s revised down from a prior estimate of $110 billion.

In April, FEMA announced plans to end the BRIC program, calling it “wasteful” and “politicized.” The agency also canceled a total of $3 billion in undisbursed funds that cities and states had applied for between fiscal years 2020 and 2023. In June, the California state legislature identified $870 million in BRIC-funded projects across the state “that will now need to seek alternative funding sources,” as Atkinson put it in a recent SPUR article. That includes the Bay Farm Island project.

Then, in July, 20 states, including California, sued the Trump administration over its cancellation of BRIC. A federal judge in August barred the administration from using BRIC funds for other purposes until that lawsuit is resolved, but cities, states and community organizations are moving forward under the assumption that they won’t see those dollars anytime soon.

Alameda’s former naval air base. Photo: Maurice Ramirez

For Bay Area groups like BCDC, BayCAN and SPUR, the power of federal grants lies in their sheer size. City, county and state grants, plus private donations from philanthropists, help fill in the gaps, but you’re unlikely to find $50 million from a single source unless it’s the federal government.

“Really large dollar amounts from BRIC had been allocated to the region, and those have been withdrawn. So there’s not a good way to just stitch together other funding sources because implementation dollars are so large,” says Carolyn Yvellez of BayCAN. “That means really well-planned projects that are ready to go … those need to be rethought. Where is the funding shift coming from?” (About $350 million of BRIC grants were promised to the nine counties in the Bay Area region between 2020 and 2023.)

That’s where an opportunity arose to rethink climate adaptation funding for the future, and to diversify sources of money for these projects, according to Yvellez, Fain, Atkinson and Mieler. Yvellez added that “we recognize … that the reliance on grant dollars is just not sustainable.”

Bay Trail on Bay Farm Island. Photo: Maurice Ramirez

Some ideas for alternative revenue sources that they’re looking into: public-private partnerships, collaborations across jurisdictions (like the Oakland-Alameda Adaptation Committee) that can reduce overhead costs, regional funds that pool taxpayer dollars to support big projects, and attracting bigger philanthropic investments into climate adaptation, among many others. They’re also excited about the possibility of tapping into larger pools of money meant for all kinds of infrastructure improvements — in transportation, housing, energy, and water — that can incorporate climate adaptation work.

“It’s forcing us to diversify, to think bigger about what options we have to continue moving forward instead of stagnating projects,” Atkinson says. “The inaction piece is what’s going to cost us more in the future.”

Local Increments

That’s just the approach Mieler is taking with the Bay Farm Island project, breaking down the process into different stages and parts, and coming up with different strategies to fund each. Their immediate goal is to raise enough money for 60% of the project design.

Figuring prominently into this discussion is California voters’ passage of Proposition 4 last year, which issued $10 billion of bonds to raise money for climate projects. Included in that total is $1.2 billion for sea level rise, enough to offset the loss of BRIC grants allocated to the state with some room to spare.

“Prop 4, if it weren’t here, we’d be in much worse shape,” says McCormick, one of many people helping Mieler and other local planners slog through alternative funding sources. “Alameda’s a great example, because half of the programs that we identify as potential backfilling for that lost BRIC grant are Prop 4-funded.”

On a recent warm, sunny August evening at Preservation Park in Oakland, the Greenbelt Alliance honored Mieler as one of its 2025 “Hidden Heroes of the Greenbelt” for her work in adaptation planning for Alameda, and specifically her role in the formation of the Oakland-Alameda Adaptation Committee.

Danielle Mieler, left, receives award from Jonathan DeLong of the REAP Climate Center. Photo: Duncan Agnew

“Cities are really testbeds and are places for experimentation, for trying new things,” Mieler says in a video that Greenbelt Alliance made for the occasion. “No matter what’s going on at a national level, at the local level, we can focus on our own communities and responding to our own needs.”

She also mentioned the importance of preserving the Bay Farm coastline as a community benefit that can enhance quality of life in the area.

For her part, Atkinson remembers seeing flooding as a kid near the Veterans Court bridge onto the island, where she would see people fishing as she biked past.

“We built the region along the Bay, but we really put all of our industry along the water, and a lot of communities are cut off from the Bay because of that,” she points out. “And through adaptation, there’s opportunities to [make] that connection again, and also protect communities and property from flooding.”

Top Photo: The Bay is always close at hand at Paden Elementary in Alameda (photo: Maurice Ramirez)

MORE

- BayCAN Funding Tracker

- Crunching the Adaptation Numbers, June 2023

- 30 East Bay Partners Gel on Adaptation, July 2022

- Teaming up to Tackle East Bay Wet Spots, March 2024