What Exactly is a Bomb Cyclone Anyway?

It’s hard for me to imagine a scarier name for weather than bomb cyclone — the kind of California experienced on January 4, 2023 — and in the days leading up to the storm, the media frenzy amped up my fears even more. Next, PG&E and my internet provider warned me of service outages. Then, Governor Newsom proclaimed a state of emergency.

I restocked my pantry and emergency kit. I also begged my husband to stay home and fretted when he said he couldn’t take the day off. When the bomb cyclone finally came and went with little impact where we live in Solano County, it was a huge relief. Phew!

After the storm passed, though, I was left still wondering exactly what a bomb cyclone is. So I asked Richard Grotjahn, an emeritus climate scientist at UC Davis who taught a course called “Severe and Unusual Weather” and co-authored The Encyclopedia of Weather and Climate Change.

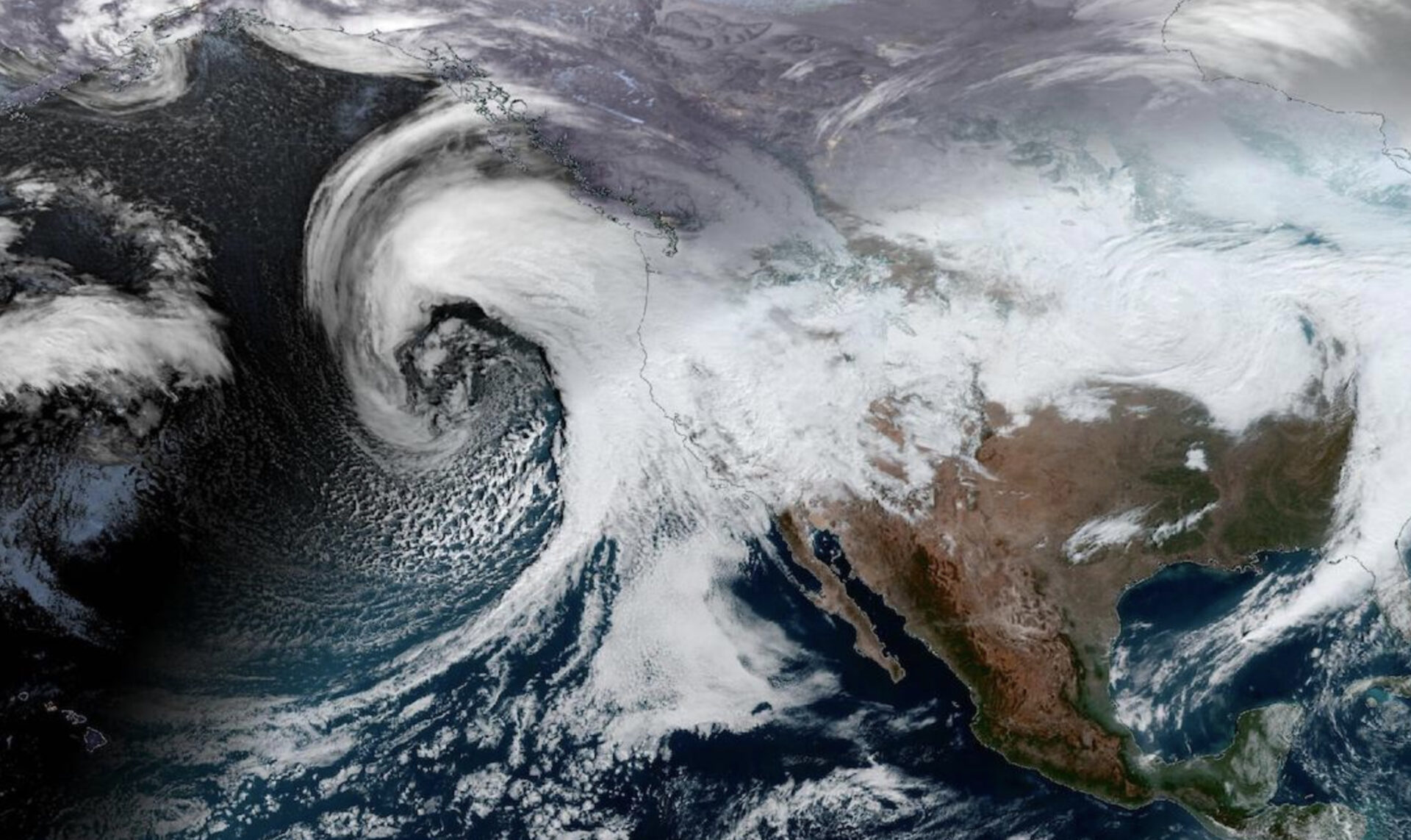

The short answer is that a cyclone is an area of low pressure with winds sweeping around it. Cyclones that hit the United States are easy to spot in satellite images because they look like enormous commas. The biggest cyclones can be the size of continents.

When the already low pressure in these cyclones drops even more really fast — at least 24 millibars in 24 hours — the wind suddenly speeds up. The cyclone gathers strength far more quickly than usual, with the potential to cause far more damage.

Meteorologists call this accelerated growth “explosive cyclogenesis,” and this is the origin of the term “bomb cyclone.” As Grotjahn points out, “it is a small step from explosive to bomb.”

Bomb cyclones are rare because the conditions have to be just right to spur this exceptionally rapid growth. “It depends on the alignment of weather patterns in the upper and lower troposphere,” Grotjahn says. The troposphere is the part of the atmosphere closest to the Earth and is about six miles deep. This is where most of the atmosphere’s water vapor is, where most of the clouds form, and where most of the weather begins.

Bomb cyclones can form when two low pressure troughs — one in the upper troposphere and the other near the ground — are offset from each other instead of being lined up with one directly over the other. This configuration, Grotjahn explains, can create fierce winds.

While last week’s bomb cyclone didn’t live up to all the hype in my area, much of California was impacted. The rarity of these extreme storms makes them dangerous. “Infrastructure and the natural environment are tested by such weather that is outside the norm,” Grotjahn says. The January 4 storm caused deaths, flooding, road closures, and power losses. Winds howled at 85 miles per hour in Marin County, and 35-foot waves crashed over cliff tops in Santa Cruz.

Meteorologists have used the term bomb cyclone since the 1970s. But Merriam-Webster only added it to their dictionary in 2020. At the time, they wondered if it would catch on widely. Today “bomb cyclone” is sure to be in almost everyone’s vocabulary.