Investing in Climate Smart Parkscapes at Coyote Hills

As I huff up Glider Hill trail in Coyote Hills Regional Park, I am unprepared for the view that is about to open up before me. Red rock crunches under my boots as I make the last push over the crest — and find myself looking precipitously down swooping gold-grass hills to the bay.

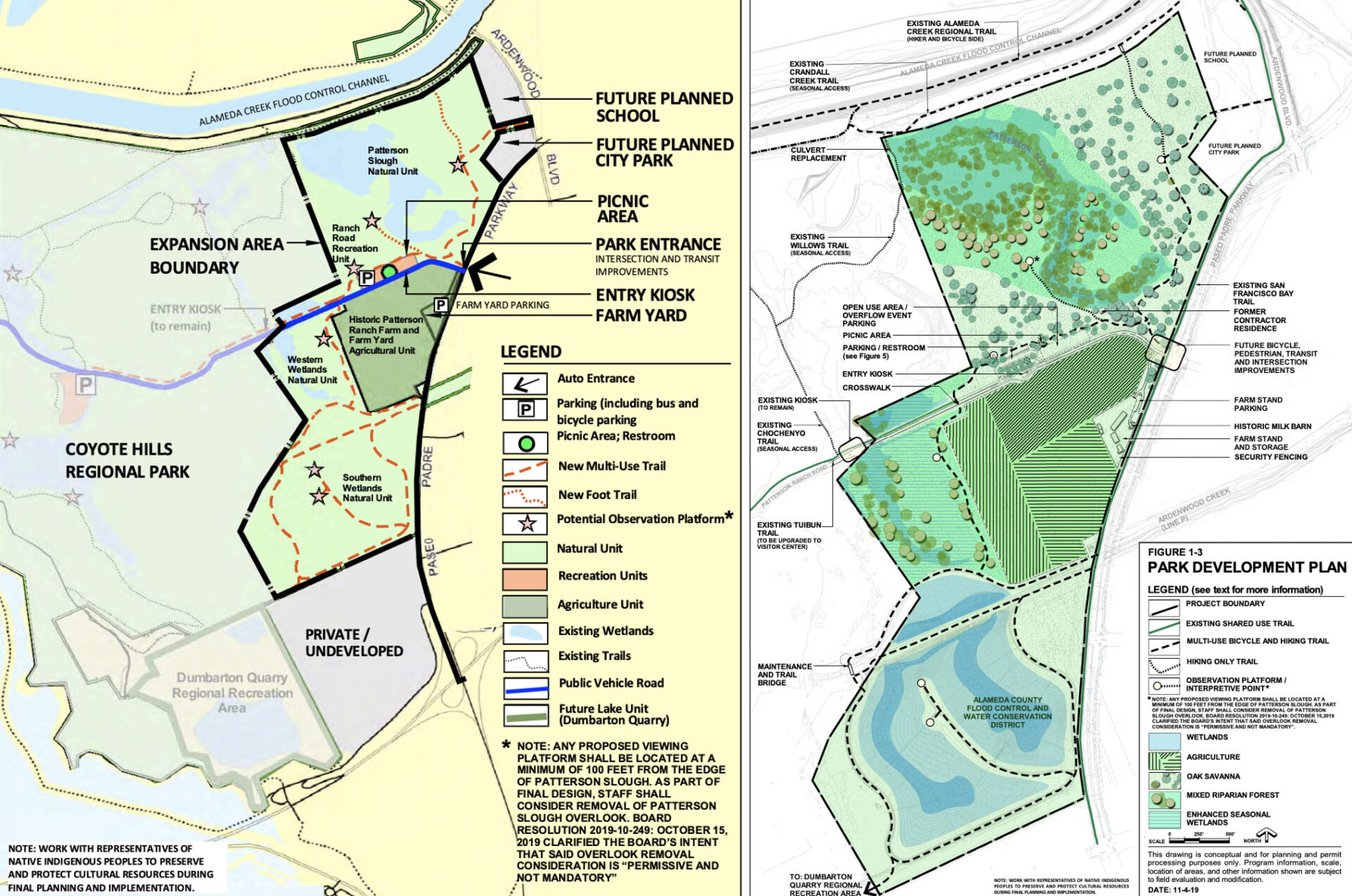

While these hills — which rise steeply from the water to an elevation of nearly 300 feet — are the most dramatic feature of the popular Fremont park, the site also boasts a working farm, a butterfly garden, marshes, and most recently a nearly-complete habitat restoration and park expansion project encompassing 170 acres.

“The big overall picture is that the project implements the state’s 30×30 initiative, which seeks to advance biodiversity and access to nature, and adapt to climate change, with all those being co-equal goals,” says Chris Barton, East Bay Regional Park District restoration projects manager.

Photo: East Bay Parks

The restoration project expands both the footprint and the ecotones encompassed by the park. Key to the park’s new look and feel is the redevelopment of a parcel donated to the park in 2014 by the Patterson family. Prior to the donation, park visitors had to pass through the private Patterson ranch to reach the park. But today the park extends to the nearest intuitive boundaries — main roads to the east and south, water to the north and west.

“Before, there was no sense of arrival to the park,” Barton says. Now, when visitors turn off Paseo Padre Parkway, they are promptly greeted by an entry kiosk. Beyond is a new parking area (complete with electric vehicle chargers) to their right, and a sustainable farm to their left.

“The park plan calls for a mix of land uses, balancing restoration with public access and agriculture,” says Barton, describing the planning process for the newest addition to the park, which began in 2019 with a $450,000 grant for planning and design from the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority. The restoration authority followed up with $3.5 million to build the project in 2021, and later $100,000 more for post-construction plant care and maintenance. Other funds came from East Bay Parks, U.S. Fish & Wildlife, and U.S. EPA.

Apart from state park bonds like Prop 68, local tax dollars make a big difference in investing in resilient landscapes. Since 2017, the SF Bay Restoration Authority has authorized $188 million in Measure AA funding for shoreline restoration around the bay ($8.7 million in grants in the last 12 months). Photo: Jacoba Charles

Climate-Smart Ecology

Throughout the 170 acres restored in this latest park expansion, restoration crews created a variety of fledgling habitats which are now getting established — including wet meadows, seasonal wetlands, willow thickets, riparian forests, and oak savannah grasslands.

“The diverse plant palette was a key consideration for climate resiliency in the Coyote Hills restoration project,” says Shalini Kannan of the State Coastal Conservancy and restoration authority. “The result is a combination of habitats that is now rare along the San Francisco Bay shoreline.”

This diversity offers a natural buffer against climate change, as different species and habitats will respond differently to changing conditions.

“In this area, the largest sea level rise concern is a rising shallow water table and groundwater salinization — more salty soil conditions can impact the establishment of sensitive natural plant communities,” Kannan says.

To inform a climate-adaptive planting design, East Bay Parks did research on the soils and hydrology of the site, and field tested a diverse mix of salt-tolerant native plant species to determine which would grow most successfully under changing conditions, Kannan says.

In addition, wetland plantings were established on mounds, which will provide a habitat gradient so future plants can adjust to changing groundwater salinity.

Taken as a whole, the Coyote Hills Park offers a regionally unique opportunity for climate adaptation because of its namesake hills. They are a unique feature along the largely flat Bayshore, offering potential for what landscape planners call “transition” habitat into uplands.

On my recent visit there, I enjoyed what the hills have to offer today: exercise, peace, views. I observed children playing at a summer camp, using pieces of cardboard to sled down (gentle) slopes. Turkeys murmured and clucked under an olive tree. Higher up, a woman and twin toddlers sat in the trailside dirt looking at poppies blooming in the dry grass. An elderly man with a walking stick passed me at a rapid clip, suggesting he makes this climb often.

Photo: East Bay Parks

At the crest of the tallest hill, benches wait between outcrops of red rock, facing the views. From here I can look west over the salt ponds and the bay toward Redwood City; or to the east, where the park is a mosaic of colors and textures, each a prism reflecting both ecotones and resiliency. The bay-facing golden hills buffer storm surge, and offer undeveloped land for saltwater-dependent plants to grow on as sea levels rise. The network of ponds and marshes at the inland base of the hills acts as a natural sponge, soaking up floodwaters as storms increase in frequency and ferocity. And the colorful hues and textures of the forest growing above the visitor center already embody some of the diversity and adaptability that the restoration project aims to expand on.

Layers of History

The park’s newest acreage connects the future to the site’s diverse history as well. The riparian portion of the restoration includes expansion of a historic willow thicket on the site where the most extensive patch of willows in the East Bay once grew. All the willow cuttings used to re-establish the thicket were micro-local: taken from existing trees either on-site or nearby, Barton says.

Tree plantings, likely valley oak, coast live oak, or buckeye, protected from deer by fences till they mature. Photo: Jacoba Charles

Meanwhile, the farm to the south of the entry road preserves a portion of the area’s agricultural history, which began in the mission era and continued until the turn of this century. Though currently unfarmed, Park employees have found remnants of past crops still seeding themselves, including cantaloupe.

“It was very important to the Patterson family that the agricultural heritage of that historic land use not be lost,” Barton says. “We worked with the farmer who had been working that field for many, many years to identify the most productive areas.”

Photo: Jacoba Charles

But agriculture is only one of the many uses that the Park landscape has seen over time. First and most significantly, Coyote Hills encompasses the ancestral homeland of the Tuiban Ohlone people, who continue to be involved with the site today. In 2022, the Tribe worked with the Park to add Tuiban names to 35 trail markers along the Chochenyo Trail.

“Makkin Mak Nommo — which means ‘we are still here’,” Monica Arellano, Muwekma Ohlone vice chairwoman, said in a statement at the time. “When people see the language and the land, they see the connection and realize that Muwekma are still present, alive, and thriving.”

Long before the Ohlone settled in the region, at the height of the last ice age, sea levels were 400 feet below what they are today, says Gary Prost, a local geologist. While the Coyote Hills existed, what stretched below them to the west was a broad valley, not a bay; even the distant Farallon Islands were on dry land.

Photo: Jacoba Charles

The 2,000-year-old shellmounds are testaments to the First People’s long relationship with the ever-changing sea. These large, conical burial mounds developed over centuries as the Tribe’s dead were covered over in earth and shells; once widespread, most have been destroyed by Spanish, Mexican, and American settlers. Today, these and other cultural resources, such as reconstructed traditional buildings, are only open to the public during scheduled programming.

Throughout the waves of Western settlement, many different people, and their diverse aims, came to use these quiet hills hugging the Bay. Salt harvesting began as early as the 1850s. The hills were quarried for stone, and dairy cows fed a growing population. In 1953 the military set up a Nike missile launch facility in the hills to respond to potential Russian bombers (soon decommissioned). Later the facility was repurposed to study the use of sonar by marine mammals, including seals and dolphins.

Visible wildlife remaining in the park includes deer, red-winged blackbirds, coyotes, and, on occasion, raptors like the white-tailed kite or northern harrier. Photo: David Harper

Park for the People

Although East Bay Parks does not rank their parks according to usage, Coyote Hills is one of their most-used parks, according to Barton. “There’s a huge draw to come out and just enjoy the hills. You can just feel like you’re in a whole other world being on San Francisco Bay,” says Barton.”

On busy weekends, the limited original parking spaces can fill up, leaving visitors to sit and wait or seek parking elsewhere.

Photo: East Bay Parks

Once they arrive, visitors will find a variety of trails and activities. The August schedule includes group hikes, a class on making (and playing with) Ohlone walnut dice, a puppet show, and an introduction to marsh ecology. Existing trails lead out between the salt ponds and south to the adjacent Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge. Eden Landing Ecological Reserve lies to the north. Planned trails will connect to the Alameda Creek Trail and the San Francisco Bay Trail, Barton says.

For now, many of the newly installed trails wind through a habitat that is still developing. Wire fences surround some small plantings to keep deer out; in other areas, branches have yet to spread to cover bare ground. But that too will be an asset for the public, once the trails open, Barton says.

“This is a great opportunity to get people out to see restoration unfold and to develop over time,” he says.

Photo: Jacoba Charles

MORE

-

A Ramble Around Pacheco Marsh, May 2025

-

Hard Park Going Soft, De-Pave Park, March 2024