Flipping the Switch on All-Electric Housing

“We have to change fast, and the right thing to do is go electric, if it’s based on a renewable grid.”

For Juan Carlos, the electricity switch was both subtle and profound.

His home in a newly-renovated unit in Light Tree Apartments is at the forefront of a trend that cities across California are trying to encourage to meet their sustainability goals: switching from natural gas appliances to electric ones. City leaders and housing developers across the state, including neighboring communities Menlo Park and Palo Alto, believe this transformation, commonly referred to as electrification, is the key to a greener future, though their efforts to encourage or mandate conversions regularly meet resistance from residents who are loath to make the change. But for Carlos the most noticeable differences between the past and the present are a new induction stove and a heat pump that offers air conditioning.

“It doesn’t affect how we cook,” Carlos says.

“From my point of view, it’s better than having gas,” his son adds.

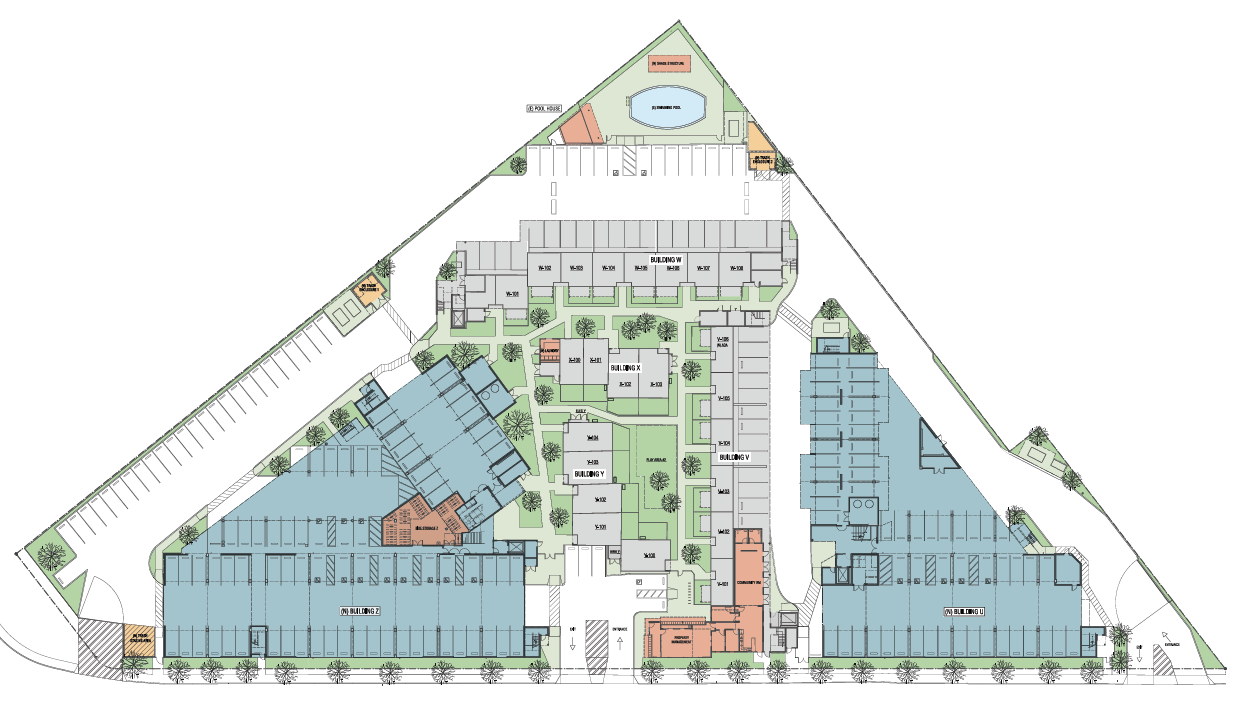

The development by nonprofit housing developer Eden Housing and the East Palo Alto Community Alliance and Neighborhood Development Organization (EPACANDO), demolished 37 apartments, renovated 57 and is building 128 new apartments. When it’s all done, there will be 185 apartments, about a third remodeled and two-thirds brand new, nine of which will offer supportive services for people who experience homelessness.

The project’s progress so far highlights some of the obstacles and lessons that affordable housing developers and providers are learning on the long road toward more sustainable power systems. The people behind this project have had to battle shifting technology, logistical challenges with electric equipment, pushback from building trades and utilities, increases in tenant utility costs and energy use, and complex funding structures to bring it to the point it is today.

Light Tree construction as of July 2022, on the cramped site next to the 101 freeway, with San Francisco Bay to the east. Photo: Lightbox Video Services.

History

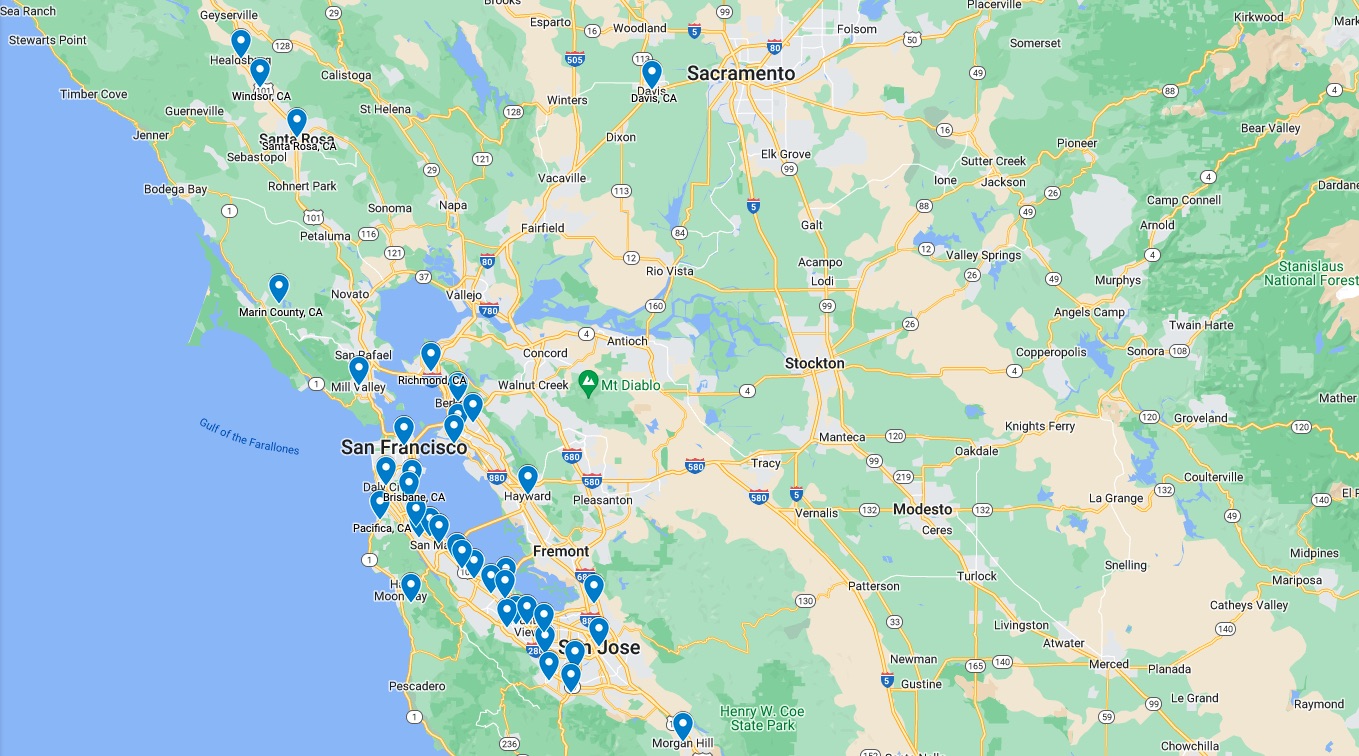

The original development, located at 1805 East Bayshore Road in East Palo Alto, was built in 1966. Redevelopment and renovation plans were approved in 2018 and the renovations broke ground in December 2020. Earlier that year, the City of East Palo Alto joined a number of other cities around the region and state to adopt Reach Codes, building codes that push for greater greenhouse gas emission reductions than the state would otherwise require. East Palo Alto’s updated codes require all new buildings to be electric, but allow exceptions for affordable single-family or multifamily homes.

In the last few years, San Mateo County businesses and residents have gained access to an increasingly renewable energy mix, driven in large part by the work of Peninsula Clean Energy. Peninsula Clean Energy is a nonprofit joint powers authority that pools the county’s energy demand to purchase contracts for electricity that’s cleaner and lower-cost than what PG&E offers. As a result, the power grid countywide delivers, as a default, electricity that’s 100% carbon-free and about 51% renewable.

The city of East Palo Alto is still finalizing its climate goals for 2030, but an April 2022 draft plan commits “to a 50 percent reduction in emissions below 2005 levels by 2030 and 100 percent reduction — carbon neutrality — by 2045.”

Shifting Technology

“Getting rid of natural gas is easy. You just close the pipe and turn it off, and that’s it,” says the project’s architect, Paul Okamoto (who is the husband of KneeDeep’s Managing Editor). The harder part, he explained, is switching to all-electric power. “It’s a moving target,” he says.

Manufacturers and contractors are still getting up to speed on the new technology and how to install it, he explained. There are two pieces of equipment that are usually gas-powered, water heaters and furnaces, that need to be replaced with electricity-powered devices, but some of those devices are still relatively new to California’s market.

For example, the initial electric water heaters planned for the development were supposed to be noisy. The design team added acoustic screens and other mitigation steps to prevent the noise from bothering the residents, only for a different manufacturer to come with a quieter model a couple of years later.

“We used to know how big a gas water heater should be to heat enough hot water for a 50-unit apartment building. How many kilowatt hours do we have to come up with to heat the same amount of water for the same amount of people? We’ve never done that before…We’re kind of on the bleeding edge,” says Tom White, Eden Housing’s associate director of building performance and sustainability.

Logistical Obstacles

As an architect, one new part of building all-electric has been that the equipment needed takes up more space than conventional gas-powered equivalents, says Okamoto.

In adding new apartments to a relatively small property, Okamoto ended up arranging a centralized water heating system with two heaters for the Light Tree apartments. Had there been more space, he might have considered a more decentralized approach, making the apartment complex more resilient — if one of the water heaters were to go out, the others would still work.

Site plan. Art: Okamoto-Saijo Architecture.

“All of these things have to be aligned — not only the financing systems, but also the manufacturers have to have the supply chains; the contractors and the architects have to be ready to specify the manufacturers’ equipment; there have to be builders and installers who are ready to install this equipment — which is not something which has been done much around Northern California, so finding qualified installers is a problem,” says Tom White. “Then there’s the question of finding who’s going to do the energy modeling for these kinds of systems.”

Trade and Utility Pushback

When it comes to adapting to new construction technology, there’s a learning curve for everyone involved, explains Nick Young, associate director for the Association for Energy Affordability, a nonprofit that, among other things, offers consulting to Bay Area multifamily properties to switch to electric heating systems.

Just like the construction industry has adapted time and time again to building increasingly seismically sound structures in the aftermath of earthquakes, the industry has to continue to adapt when it comes to electrification, Young says.

Understandably, there are times when contractors can be risk averse. “There’s a lot of liability involved in construction,” he says.

However, usually all it takes is one or two projects for building teams to work through the challenges before they’re prepared for the third and fourth projects. And these are skills that are increasingly in demand. A growing number of affordable housing developers are recognizing that installing gas infrastructure in their buildings will leave them with a stranded asset in the years to come, he says.

Yet all-electric infrastructure can require buildings to take up more space, which can put the goal into conflict with what’s often the first goal for affordable housing developers: build as much affordable housing as possible on a limited amount of land. Things like certain thresholds at which transformers have to be above ground versus underground can shape whether it’s financially feasible for a developer to go all-electric with new affordable housing.

In general, however, nonprofit affordable housing developers are leading the shift to all-electric multi-family housing developments, says Young.

“They want to not just build housing, they want to build housing that is beneficial to their residents in terms of indoor air quality…and that also addresses other social issues,” he says. “I want to emphasize how important low-income housing nonprofits are in California. They are full of very smart, very scrappy people who know how to get things done.”

Rise in Tenant Energy Use and Spending

In the end, all-electric power ends up being fairly invisible to residents. The likeliest thing residents will be able to see is more condensation on the roof drains from the heat pumps, said the architect. And, as residents like Carlos have noticed, there’s the added amenity of air conditioning.

Photo: Lightbox Video Services.

Heat pumps and hardhats. Photo: Association for Energy Affordability.

In an era of climate change, ever-hotter summers and intermittent wildfire smoke, Okamoto argues, air conditioning is only going to become more necessary for households, even in the foggy Bay. “The human body still needs a certain amount of thermal comfort,” he says.

While residents appreciate having the option to air condition their apartments, it can also lead them to use it, driving up their utility expenses. Annette Hamilton, who lives at the property, said that her PG&E bills have risen in the new building to about $120 or $130 a month from around $30 to $40 in an apartment where she had no air conditioning.

As more developments make the switch to electrification, the burden of maintaining aged gas infrastructure necessarily falls on fewer customers. It’s a critical equity challenge, White says, to make sure that economically vulnerable people aren’t left behind footing the bill for remaining natural gas usage.

Complex Funding Structures

Because affordable housing projects receive public funding, the projects typically have to overcome more regulatory hurdles and address more conflicting public policies than private developments. Okamoto says the different rules “dig at each other,” which drives up the costs.

“Since we have public money, we have to design and build perfectly and correctly,” he says.

Ultimately, an EPIC grant from the California Energy Commission provided technical support and consulting along with other financial support to push the all-electric project forward.

Even with these challenges, building electrification represents one of the most promising tools for reducing greenhouse-gas emissions. In neighboring Palo Alto, which is trying to cut carbon emissions by 80% by 2030, a key goal is to switch more than three quarters of single-family homes from gas appliances to ones powered by clean electricity. Electrification is now the city’s top priority when it comes to meeting its green goals.

In terms of other green goals, statewide pressure to meet the dire immediate need for more affordable housing units still trumps longer term concerns, like East Palo Alto’s vulnerability to sea level rise, when it comes to decisions about how to use space and budget. At Light Tree, utilities and transformers remain in the wet zone at or below ground level. As climate change impacts deepen, affordable housing will remain at the frontlines of complex environmental equity trade offs.

In the meantime, cities, developers and architects are taking what steps they can toward a more sustainable future.

“If we’re really going to solve this climate crisis, and adapt to this changing world, we have to change fast and the right thing to do is go electric, if it’s based on a renewable grid,” Okamoto says.