CEQA Reforms: Boon or Brake for Adaptation?

Affordable housing in San Francisco. Photo: Joey Kotfica

“If we’re not addressing our housing crisis within the region, we are putting more people at risk of climate impacts by pushing them into the higher fire risk zones and areas of extreme heat inland.”

While housing advocates and developers are cheering new legislation that will sharply limit the California Environmental Quality Act, many environmental groups are outraged by what they say was a rushed and opaque process that will eviscerate environmental protections in the state. Additionally, they and other analysts worry that although some provisions of the new laws are touted as enhancing climate resilience, others may create missed adaptation opportunities, or worse, outright hamper resilience efforts.

Critics of CEQA, which requires projects needing government approval to undergo rigorous review to assess potential environmental impacts and identify mitigation measures, have long contended that it exacerbates the state’s housing crisis by impeding development.

Billed as reforms that will streamline housing and infrastructure development, AB 130 and SB 131 were enacted this summer as part of the state budgeting process. Under the new laws, infill housing and other types of development that meet certain criteria, including size, location, and density requirements, will be exempt from CEQA.

The changes will likely advance the goals of Plan Bay Area, a long-range plan developed by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the Association of Bay Area Governments to make the region more resilient and equitable, says MTC’s Planning Director Dave Vautin.

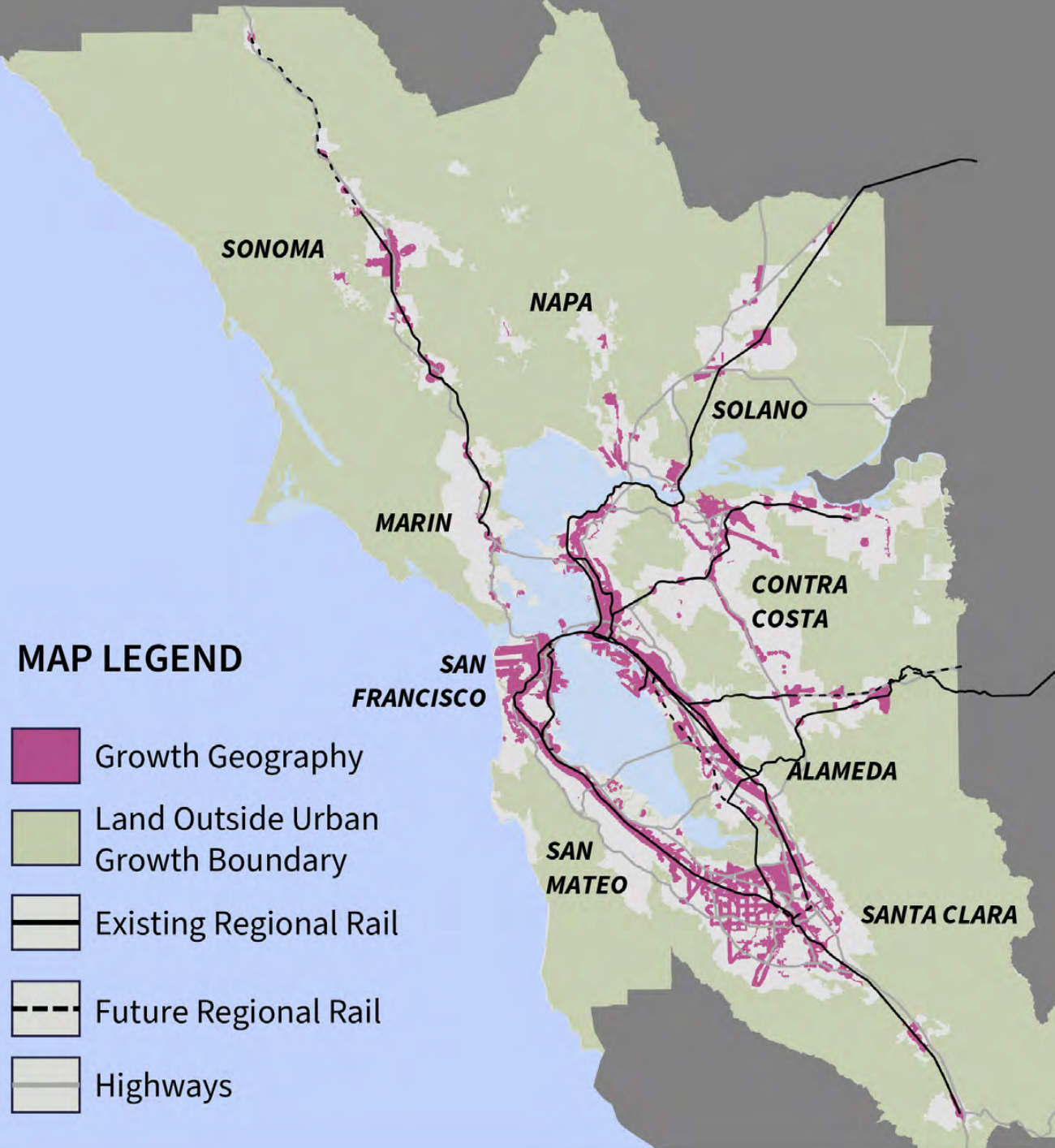

Plan Bay Area 2050+ focuses 95% of new households and over 70% of new jobs into places close to transit and prioritized for future growth. Map: MTC/ABAG

“Plan Bay Area has ambitious housing goals that are necessary to address our affordability crisis, which means that changes in policy at the local, regional, and state levels are necessary to unlock opportunities for folks to live in the region,” he says. “If we’re not addressing our housing crisis within the region, we are putting more people at risk of climate impacts by pushing them into the higher fire risk zones and areas of extreme heat inland. This CEQA streamlining action is one piece of a larger puzzle that is necessary to make it easier to build homes, so we can both address the region’s cost of living challenges and reduce the number of folks who have to move outside of the Bay Area and commute into it.”

Meredith Parkin, of consulting group Environmental Science Associates, concurs. “Encouraging infill housing to reduce sprawl and enabling efficient land use will really contribute to climate resilience,” she says.

Stymied Resilience Rules?

What is still unclear is whether the new exemption will help or hinder efforts to steer new construction away from zones vulnerable to flooding and fire, or hamper the adoption of more resilient building practices.

For example, a provision of the new laws freezes building code changes until 2031. “Many times [codes] are updated based on new technologies, green building practices, and safety standards,” says Parkin, noting that there has been “some debate” about whether the freeze will result in new developments that are not as safe, or water or energy efficient, as they might otherwise be.

Gilroy resilience event. Photo: Greenbelt Alliance

The building code freeze also conflicts with one of the adaptation strategies identified in the Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plan, notes UC Davis’ Mark Lubell. The RSAP calls on local governments to identify ways they might change zoning ordinances and building codes to be more resilient.

“There are two government directives that are counter to each other here,” says Lubell, “and that could make some of this local stuff more difficult to do as far as updating local ordinances.”

Lubell also notes that the new laws do little to direct new development to areas with less vulnerability to the effects of climate change.

“In the Bay Area, for example, we’re seeing a lot of new housing developments getting proposed in low-lying areas that are vulnerable to flood risk, because that’s where the space is,” he says. “If you’re going to try to accelerate the speed at which the housing supply grows, it should be done alongside trying to manage where it goes.”

Although the housing-related CEQA exemptions are meant to pertain only to infill development, critics say that the way the bills are written leaves lots of wiggle room. Any land that was previously developed for urban use qualifies, as does land where at least 75% of the area within a quarter-mile radius is developed for urban use.

“That could be the outskirts of a city if the radius was arranged right,” says Frances Tinney of the Center for Biological Diversity. “It opens up a lot of land that is not necessarily the classic thing you think of as infill, which is literally already within a city.”

A provision known as the near-miss rule could also lead to development in vulnerable areas, says Tinney, without adequate analysis of risks and mitigation measures. Under the rule, developments that meet all the criteria for CEQA exemption except one condition (such as potential value of the project site as habitat for rare, threatened or endangered species) only need to do an environmental impact analysis for that condition.

Every time an extreme fire or flood event wipes out a community there is increased pressure to scrap important environmental protections and rebuild as fast as possible (LA fires of January 2025). Photo: Ward DeWitt, I-Stock

“That is going to result in really truncated EIRs,” says Tinney, who is concerned that developments in wildfire-prone areas could go forward without detailing risks and creating evacuation plans, as would be required by a full CEQA review. “In a lot of cases, developers are going to build unsafe housing, and they’re not going to have to divulge that or make a plan for protecting the people who live there. “

Short-circuiting CEQA review could also mean missed opportunities to enhance the resilience and sustainability of development, says the Center’s Aruna Prabhala.

“Often the elements that really improve community climate resiliency are part of larger projects,” Prabhala says. “If you cut out the community engagement and feedback that happens during the environmental review process, you take away the opportunity to say, ‘Hey, have you thought about including more rooftop solar? Can you include some publicly available easy charging stations?’ These things have helped make California more climate resilient. If you take out the EIR process, those opportunities are lost and they don’t come back.”

Community comments on flood zone maps of Alameda island at resilience fair in September 2025. Photo: Greenbelt Alliance

Environmental and community groups have other concerns about the CEQA revisions, particularly a provision that would allow advanced manufacturing on any land that had previously had any kind of industrial use.

“This means that the most polluting, resource intensive facilities that we have in California —chemical manufacturing, strip mining, refining production, metal scrapping, computer chip manufacturing, lithium batteries — no longer have to do environmental review if they’re on industrial land,” says Asha Sharma of the Leadership Council for Justice and Accountability. Both light industrial and heavy industrial land can often be “very close” to homes, schools, and neighborhoods, and to polluted communities, she says. “And you will have way less analysis of water and energy use, which is really important from a climate perspective.”

A Win for Transit-Oriented Development

Concerns about CEQA exemptions aside, the new laws do have some good news for sustainable growth. Obviously, not every new development in California will be eligible for CEQA exemption, and those that don’t qualify will still need to provide mitigation if they increase vehicle miles traveled (under CEQA, any project that doesn’t decrease VMT is presumed to increase them). A new provision will allow developers to mitigate for VMT by contributing to a state Transit-Oriented Development Implementation Fund to support development near public transportation.

Bay Bridge toll plaza in 2025, showing those who chose to drive over riding BART or ACT Transit for the same commute. Photo: Halbergman, I-Stock

“The methodology for how that will be assessed as far as mitigation value is something that is going to be determined through a rule making process by the Governor’s Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation in the coming year, and that process will be extremely important to be engaged on,” says Matt Baker of the Planning and Conservation League. “Figuring out that monetary value, and making sure the mitigation is actually commensurate, is very, very critical for a VMT mitigation bank to be effective. So there are going to be a lot of eyes on that.”

MTC’s Vautin says it may be too soon for the ramifications of the CEQA changes to be clear. “There have been previous CEQA streamlining bills that the state has pursued, and it does take time to understand the magnitude of impact. I think we’ll have a better sense of some of the implications and consequences of the bills as we go forward over the next couple of years.”