Even SCAPE, skilled designers of climate-ready infrastructure, were caught off guard by Hurricane Ida. Their New Orleans staff had to evacuate; their New York staff saw deadly flooding first-hand all around. The well-known landscape architects and designers had just kicked off construction for some innovative “Living Breakwaters” off the South Shore of Staten Island, post-Hurricane Sandy. The firm was also working around the country on various projects including tidal terraces for San Francisco’s own China Basin Park, and a horizontal levee for the East Bay’s Hayward, pre-rapid sea level rise. But even for these far-thinking folk, the last six months have seemed extreme.

“It’s easy to think a western wildfire is not your problem until you wake up in the morning in New York with orange smoke in your sky. Then with Ida, the collective shock and surprise, even for professionals like me working in the field, was visceral. Climate change was no longer a professional consideration but a personal one,” says SCAPE’s Design Principal Gena Wirth.

While the weather is top of mind for many, others are riveted to congressional antics over the long-awaited massive spending bill designed to fix the nation’s roads, bridges, and broadband as September evaporates. We’ve rarely heard the tonguetwister “infrastructure” bandied about so much. But for those devoted to designing all things climate-ready and habitat-friendly, infrastructure brings to mind oysters, marshes and willow-topped levees, not potholes.

“There are no solutions, there are only choices.”

A variety of grey, green and rainbow infrastructure will be needed to weather the future. This year’s fires, floods, and hurricanes have put the spotlight on dry forests and low shorelines. Meanwhile, the last vestiges of natural ecosystems across the country are suffering the extremes, not to mention continued human encroachment on their territory.

“We have been decimating the physical landscape that might protect us – the baylands cushion in the Bay Area, the coastal wetlands in Louisiana,” says SCAPE’s Founding Principal Kate Orff. “The very moment when we need these systems most, to help us adapt, is also the moment they are in collapse. We need both rapid decarbonization and to invest in the natural systems we have lost. “

This September, California earmarked $768 million for “nature-based” infrastructure projects.

Solutions must fit the local landscape, jump through myriad regulatory hoops, and gain support from surrounding communities, of course. They must also be “multi-benefit”—feeding two birds with one seed.

The urgency is palpable. Even large federal bureaucracies are stirring: FEMA is funding relocation not just rebuilding; the US Army Corps of Engineers, famous for its way with concrete, is elevating a long-standing but little known “engineering with nature” department. In September, program chief Todd Bridges announced new international guidelines for natural and nature-based infrastructure in the wake of 22 weather and climate-related disasters in 2020, not to mention this year’s heat domes, hurricanes, fires and floods. The Corps worked with 70 NGOs and other organizations to craft the guidelines as a critical technical reference.

“We need to increase the portfolio of natural and nature-based techniques, measures, and solutions that can be combined to build flood risk management systems and future resilience,” Bridges said in a Webinar. This, from the Corps, verged on inspirational.

“We have these polar extremes of tested approaches, relocate or displace,” says Wirth. “But we can’t forever be building bigger or better infrastructure. We need to test solutions that layer protection and include living with water.”

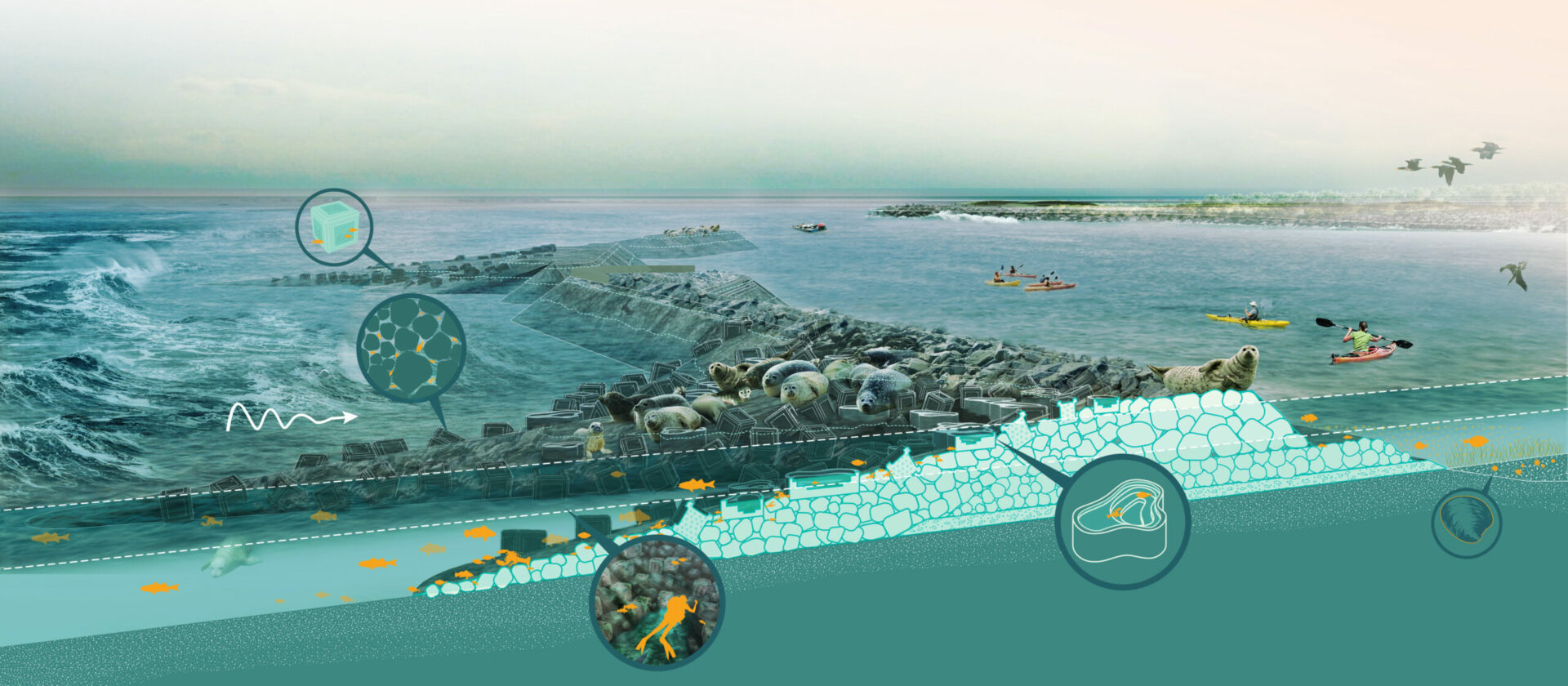

One thing is for sure, we’ve got to get a move on. One innovative project just going in the waters off the South Shore of Staten Island this September took almost seven years to get through planning and permitting! This summer, cranes began lowering “marine mattresses” to build what SCAPE calls “Living Breakwaters” to protect the shore from storms like 2012’s Superstorm Sandy.(Sandy destroyed 600,000 homes, killed 293 people, and cost $70 billion; this year’s storms look to have even more wind at their backs.) While the mattresses are more conventional hard infrastructure, the associated oyster habitat elements are more nature friendly.

The breakwaters design got top billing in a compelling August 2 article in the New Yorker by Eric Klinenberg. The story’s headline asks this question: The seas are rising, can oysters help? And it puts the kibosh on “tl;dr” (too long; didn’t read in an editor’s and texting shorthand). Sometimes a good long read is what it takes to understand the ins and outs of rebuilding by design, achieving multiple benefits, and working with nature.

The story explores a variety of oyster-driven innovations and deployments on the East Coast and Gulf Coast, but fails to mention our own West Coast experiments. From the Puget Sound to San Diego Bay, scientists, engineers, and conservancies have built more than a dozen fledgling “Living Shorelines” in different shapes at sizes. Here in the Bay Area, practitioners use reef balls and castles made of native sand and local cement, and topped with clean Pacific oyster shell. It’s all about building blocks crafted to survive and thrive in local conditions.

Oyster reef balls in the Giant Marsh experimental living shoreline in San Francisco Bay. Photo: Jak Wonderly

“Our species are different and our tidal range, shoreline slope and substrates are really different, ” says Marilyn Latta, Project Manager for the California Coastal Conservancy. Latta has spent heaps of time and money on eradicating Atlantic cordgrass, for example, a strong wetland habitat builder back East but a hybridizing invasive monster that is challenging the native ecosystem out West.

In 2019, Latta and 19 partners built three new oyster reefs, surrounded by planted eelgrass beds, off Point Pinole near the City of Richmond. Partners at ESA Associates, another national practitioner of nature-based engineering, are measuring the resulting changes in wave energy and shoreline erosion. Monitoring this summer showed more oysters than ever before (see video). “Physically it’s a lot lower cost to build these projects on the East Coast in the intertidal areas of private homefronts,” says Latta.

California’s coast, including its bayshores, presents a timesink of permitting obligations and environmental protections; in the Bay Area regulators have fielded a one-stop permitting shop, but progress is still slow. Latta points to progressive state and federal approaches in Maryland. “We’re interested in learning from and mimicking progressive states.”

The Bay Area has been experimenting with wetland restoration and living subtidal infrastructure for decades now. The ring of restored marshes that is the result goes a long way toward protecting those landing airplanes, running industries, or living and working near the water. Over time, these habitat friendly building techniques have been polished to include elements adaptive to heat, storm surge, and drought (wild swings in freshwater flow from watersheds, for example, affect oysters, eelgrass and other marine species).

“The Bay Area is great at grounding projects in ecological science, which is good for the nature-based side of infrastructure but not for the infrastructure side. We need more regulatory adaptation and experimentation with living infrastructure.” says SCAPE’s Gena Wirth, who experienced this first-hand while leading the “Public Sediment” team of the 2018 Bay Area Resilient by Design Challenge.

The challenge asked eight teams from around the world to come up with creative solutions for different at-risk shorelines, ranging from a sponge for Silicon Valley and East Palo Alto to floating housing in Oakland to the release of more mudflat-building sediment from the huge Alameda Creek flood control channel (the Corps at its early best). In the latter, Wirth found it challenging to reframe flood control management views of sediment as a much-needed resource for adaptation, rather than a waste that reduced flood capacity. That conversation goes on.

More recently SCAPE has been working with a group of public and private property owners on the Hayward shoreline planning for sea-level rise. Goals were to pack tidal restoration, recreation areas, and stormwater storage all in the same shore, an area already crammed with utilities, industry, roads, parks and expensive real estate. “We worked hard in our three alternatives to hybridize the infrastructure to meet multiple needs wherever possible, but there really wasn’t as much space as I would have liked to see for stormwater,” says Wirth.

Across the Bay, SCAPE again squeezed some big ideas into a small site in San Francisco’s China Basin. In early October, they’ll complete construction drawings for a 4.5-acre waterfront park adjacent to the Giants ballpark. The new park creates elements of ecological health and adaptation to sea-level rise on the doorstep of the massive urban developments of Mission Rock.

“It’s designed to be viable and stable 80 years from now, even with sea level rise,” says SCAPE’s Technical Principal John Donnelly. Steps taken include over-excavation and lightweight fill to achieve resilience for the site at future elevations. “If we didn’t take these steps, the whole park could slough off like mayonnaise into the Bay,” he says. (The fill includes lightweight cellular concrete that captures air bubbles.) The fill is also designed to interact with rising groundwater. “You have to make sure it’s not so lightweight it’s buoyant and floats.” Just a few of the construction considerations associated with our brave new shorelines.

“The site is dynamic and designed for change,” Donnelly sums up. “The tidal shelves make the rising sea level visible. Over time, portions of the footprint will become open water.”

Of course, not all communities will have the resources or public attention to keep them out of harm’s way, nor will any infrastructure bill or FEMA budget be adequate to field all climate extremes on everyone’s property.

“You can’t help but think about how devastating it is for those outside the new levee system in New Orleans,” says Wirth. “But the idea of making everyone safe is not realistic. The level of coordination it would take in our varied system of infrastructure is overwhelming. “

The buzz now, among both designers and practitioners on both coasts, is “capacity building.” We need to get more pilot projects built, and then we need to scale them on fast-forward. But we can’t lose sight of the communities most at risk, or outside the planning loop or power structure, either.

Kate Orff warns: “Green solutionism is not going to absolve us from difficult trade-offs. There are no solutions, there are only choices. It will be expensive and require phased investments over time.”

More:

- The Seas are Rising, Could Oysters Help by Eric Klinenberg in the New Yorker, August 2, 2021

- New Monitoring Data From Two-Year Old Giant Marsh Living Shoreline Project, Estuary News, June 2021

- A Multi-Habitat Experiment at Giant Marsh, Estuary News, June 2019

- SCAPE Studio’s Living Breakwaters Enters Construction, September 2021

- International Guidelines on Natural and Nature-based Infrastructure for Flood Risk Management, USCOE

- Full Report

- Recorded Launch