Bayfront Redevelopment on a Landfill Sparks Pollution and Flood Concerns

A contentious plan to redevelop an office park at the edge of Belmont Slough is spotlighting the challenges that closed landfills can create for planners and cities trying to protect their shores from rising waters. The property is one of approximately 50 such sites ringing the Bay.

“The old landfills were essentially built into former marshland on the margin of the San Francisco Bay,” says Keith Roberson of the Regional Water Quality Control Board, which has regulatory authority over the sites. As the ocean expands and the bay and groundwater rise, “these landfills are going to be subjected to higher water levels and probably more wave action and erosion,” with the potential to create environmental problems.

The 85-acre Redwood Life campus sits atop the Westport landfill in Redwood Shores, which was used from 1948 to 1970 for the disposal of municipal waste and incinerator ash. In the 1980s it became one of the first bayside landfills to be redeveloped. The property is bounded by residential neighborhoods on one side and a section of the Bay Trail on another; the Redwood Shores Ecological Reserve lies just beyond the levee that protects the area.

The landfill, which rests on unlined Bay mud, is subject to a water board order requiring a hard clay cap and perimeter barrier wall, a leachate collection system, a methane gas venting and monitoring system, groundwater monitoring wells, and regular inspections and monitoring programs. All these measures aim to ensure the old dump doesn’t pollute its surroundings and that methane from decomposing waste doesn’t build up to dangerous levels.

Redwood Life Campus entrance.

In 2023, after property owners Longfellow Real Estate Partners unveiled plans to replace the 20 existing two-story buildings with 15 multi-story ones, generating significant community concern, the Redwood City Council launched a planning and environmental review process to assess the trade-offs and benefits of redeveloping the Redwood Life campus. The result, known as Alternative 2, calls for reducing the number of new buildings to 12 and responds to some of the other community concerns.

This spring, Longfellow informed the city of its intent to pursue Alternative 2 in place of the original plan. However, some neighbors and environmental groups still have concerns about the size of the project and its potential for ecological damage.

“What they want to build is gargantuan,” says neighbor Steve Goodale, who has coordinated some community responses. “It’s too close to homes and it’s too close to the slough.”

Regulators share some concerns about landfills as development sites.

“A landfill surface is very uneven,” says Roberson. “It’s not very well equipped to support the weight of any building, much less a large building. There is also differential subsidence, where some parts of the landfill surface sink faster than other parts and produce a really irregular surface that simply can’t be built upon.”

To contend with this reality, developers must sink support piles — possibly hundreds, or even thousands — through the landfill and Bay mud into the geology below. It’s these piles that alarm regulators and neighbors. “Anytime you drill a hole through a landfill you are producing a vertical conduit that could act as a point of migration for leachate that’s inside the landfill to leak out and go into the underlying groundwater,” says Roberson. Leachate, the liquid that forms inside the landfill, varies in composition depending on the landfill, ranging from “innocuous to fairly alarming,” according to Roberson. At Westport, monitoring has identified volatile organic compounds within the barrier wall.

Current campus and Belmont Slough. Photo from Plan Redwood Life website.

Gita Dev, of the Sierra Club’s Loma Prieta chapter, says her group is concerned that not enough is known about the condition of the landfill and the impact of development on the surrounding ecosystem, including the Redwood Shores Ecological Reserve.

“What might drilling hundreds of piles do in terms of releases of toxins into the Bay, into the wildlife refuge? We think they should not proceed until they have a better idea of the potential damage,” she says.

During a January 2025 webinar on the project held as part of the city’s community engagement program, Troy Reinhalter of consultant Raimi + Associates told participants that if and when any redevelopment is approved for the site, the developers will probably be required to do “additional waste characterizations and delineation studies, likely based on a lidar type of study.” (Lidar is an advanced remote-sensing method used for a range of applications including mapping and atmospheric research.)

Roberson says the development plan will have to include a detailed pile installation program. “We will need to feel comfortable that they are going to be able to seal these holes as they’re creating them, so that leachate doesn’t flow into them and leave the landfill.”

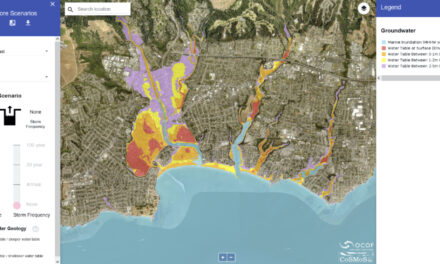

Sea level and groundwater rise exacerbate the challenges of redeveloping landfills.

“Landfills are going to see some saturation of the waste inside them,” says Roberson. Although he acknowledges that this “sounds like a horrific problem,” he notes that Bay mud itself is “a pretty good barrier to fluid migration” that can help protect the surrounding waters. Similarly, the mud provides some protection against leachate leaks from construction piles: “It’s kind of self-sealing,” Roberson says, noting that there are certain construction techniques that can also mitigate the problem.

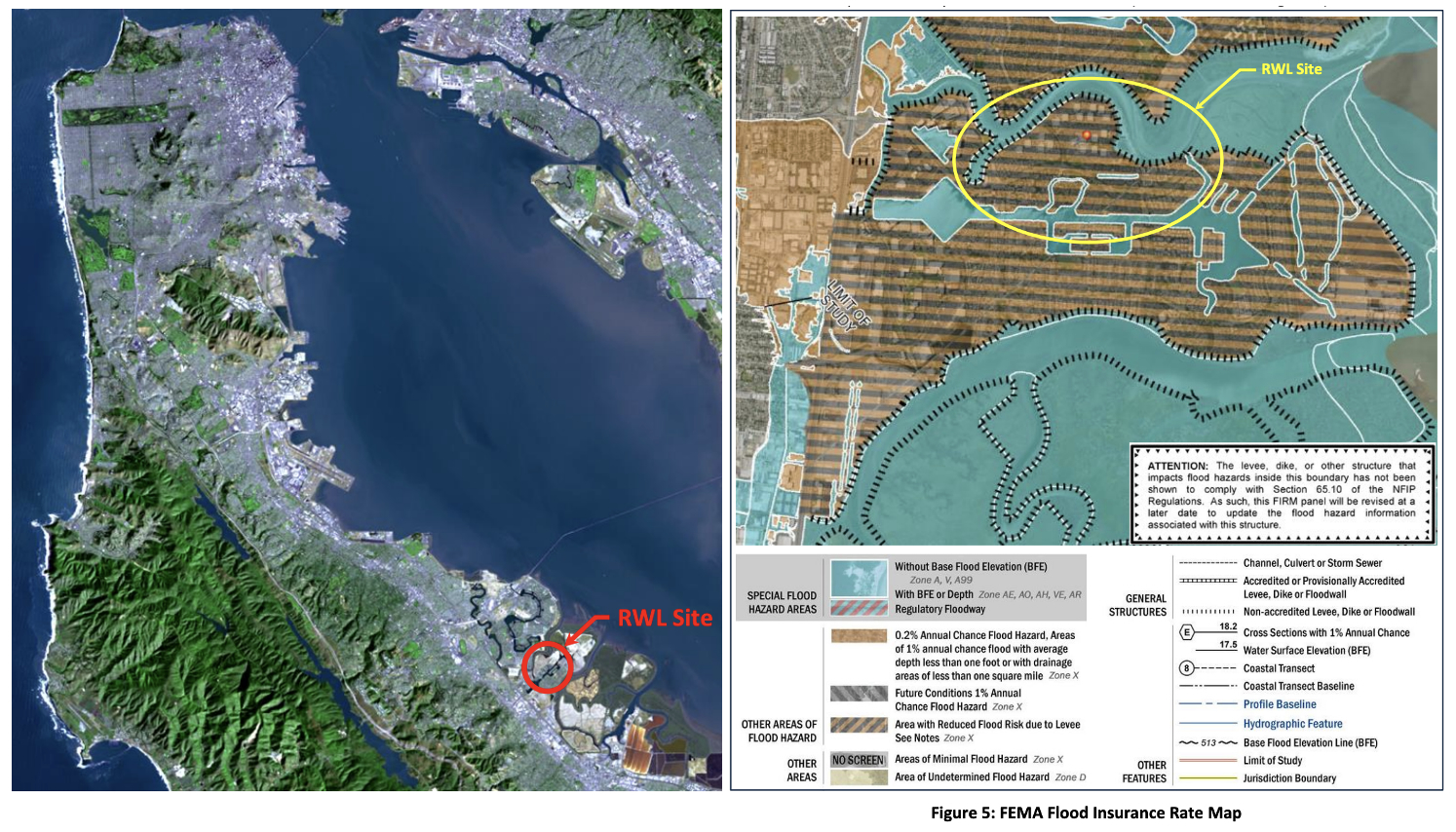

Analysis of flood risk and current FEMA mapping of the Redwood Life site, May 2024. Map: Moffett & Nichols

In October 2022 the Regional Board began requiring bayfront landfills to develop long-term flood protection plans. Owners must identify vulnerability to both surface sea level and groundwater rise and describe the steps they will take to protect against it. The plans must be updated every five years.

The Redwood Life area is already subject to flooding during high tide events, and the redevelopment plan will figure in a broader effort to protect Redwood City’s low-lying areas from sea level rise. Together with its neighbors Belmont and San Carlos, the city is preparing to hire a consultant to begin the process of raising the levees that protect their joint shoreline — including the one that protects Redwood Life — in response to new FEMA flood maps. At the same time, the San Mateo County Flood and Resilience District (known as One Shoreline) is preparing a Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plan for the cities of Belmont, San Carlos, Redwood City, Menlo Park, and East Palo Alto.

Neighbors Steve & Nina Goodale, who are concerned about many aspects of the Redwood Life redevelopment plan, recorded this breach in the Bay Trail levee into the landfill detention pond during a recent king tide. The levee is one of several that must be raised to address increasing flood risk.

One Shoreline’s Len Materman says his agency has been in conversation with the city, the developers, and their consultant teams for some time. “Our whole pitch is that [Redwood Life] is a very large, impactful development that touches water, and the water-facing portion of the development needs to [accommodate] substantial sea level rise and connect to new shoreline infrastructure adjacent to the property.”

Materman thinks the redevelopment presents a rare opportunity that the region, in its efforts to address sea level rise, should make the most of.

“A city will have a major development going in right on the shoreline once every five or ten years or more. So the question is, how do we take advantage of that?” he says. “There are all these things going on at the same time that are in planning and early design, and it’s a challenge to fit it all together. But we’re trying to deal with big, transformative changes.”

Other Recent Posts

Six Months on the Community Reporting Beat

The magazine worked with four journalists in training from community colleges, and began building a stronger network in under covered communities.

Rio Vista Residents Talk Health and Air Quality

A Sustainable Solano community meeting dug into how gas wells, traffic, and other pollution sources affect local air and public health.

New Year Immerses Concord Residents in Flood Preparations

In Concord, winter rains and flood risks are pushed residents to prepare with sandbags, shifted commutes, and creek monitoring.

What You Need to Know About Artificial Turf

As the World Cup comes to the Bay Area, artificial turf is facing renewed scrutiny. Is it safe for players and the environment?

Threatened by Trump’s Policies, GreenLatinos Refuses to Back Down

National nonprofit GreenLatinos is advancing environmental equity and climate action amid immigration enforcement and policy rollbacks.

Noticias en español

Encuentra más historias en español esta primavera, dentro de nuestro boletín KneeDeep con vecinos, y aquí en nuestro sitio.

Los residentes de Rio Vista hablan sobre salud y calidad del aire

Una reunión de Solano Sostenible discutió cómo los pozos de gas y el tráfico afectan el aire local y la salud pública.