Hopes and Fears for Sierra Snowpack

California Water Resources officials conduct the second snow survey of the season at Phillips Station, just south of Lake Tahoe. Photo: Sara Nevis

A series of powerful snowstorms are finally blanketing the Sierra Nevada this week, welcome news for skiers and climate scientists alike after a January that left California’s snowpack shrinking instead of growing.

But just weeks ago, despite heavy precipitation from October through December, a monthlong dry spell and a warm January had experts and state officials worried about soil moisture and wildfire risk for the upcoming summer.

In late January, the California Department of Water Resources conducted its second snow survey of the season at Phillips Station near Lake Tahoe. The results were discouraging — the 23 inches of snowpack at the site held eight inches of water at the time, just 46% of the Jan. 30 average. The same measurements taken at more than 250 other locations in California showed that Sierra Nevada snow statewide was carrying 59% of its average water for this time of year.

That’s despite early season snowfall leading to a snowpack that was 89% of the average for Jan. 1. In just a few weeks, warm temperatures and a lack of precipitation contributed to the snowpack losing 5% of its volume.

“I haven’t seen this much liquid running under the snowpack at this time of year. It’s been warm, and so that is running off. It is in the creeks, it is in the rivers, and it is heading to the reservoirs,” Andy Reising, DWR’s manager of snow surveys, said at a press conference at Phillips Station. “Thankfully, it’s not a lot. Five percent is some, but we don’t want to be going backwards this time of year, so we need some more storms.”

According to climate scientist Daniel Swain, at least one site in every western state was reporting record low snow water content in mid-January. Data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service also shows that “at least one ground-based monitoring station in every major western watershed recorded the lowest SWE [snow water equivalent] in at least 20 years on January 26.”

Just a couple of big, cold atmospheric rivers could bring the region back up to speed, “but we need those to happen, and there’s no guarantee,” Reising says. Much to his relief, one such system is dumping several feet of snow on the Lake Tahoe area right now — but we won’t know how much of a dent it will put into the region’s snow deficit until the next survey in two weeks.

Other Recent Posts

Building Sustainably with Mass Timber

This building method can help clear forests of smaller trees that burn easily while also reducing the carbon footprint of new homes and offices.

Hardscapes That Filter Rain

Heavy rain can overwhelm storm drains and pollute waterways, but materials like permeable pavements help filter runoff and prevent flooding.

The Gray-Green Alchemy of Baycrete

Baycrete is a nature-based hybrid of concrete, shell, and sand designed to attract oysters and create shallow water reefs in SF Bay.

Tools Tweak Beaver Dams

Humans find ways to co-exist with beavers, tweaking dams to prevent flooding and create more climate resilience.

Errands by E-Bike

Electric cargo bikes are climate-friendly car replacements for everyday activities, from taking the kids to school to grocery shopping.

A Rare Plant Tough Enough to Save the Future Bayshore

Sea-blite can thrive in adverse conditions, buffer shores from waves, hold sand and soil in place, and clamber up eroding cliffs.

Reforming Rules to Speed Adaptation

Bay Conservation and Development Commission to vote early this year on amendments designed to expedite approval of climate projects.

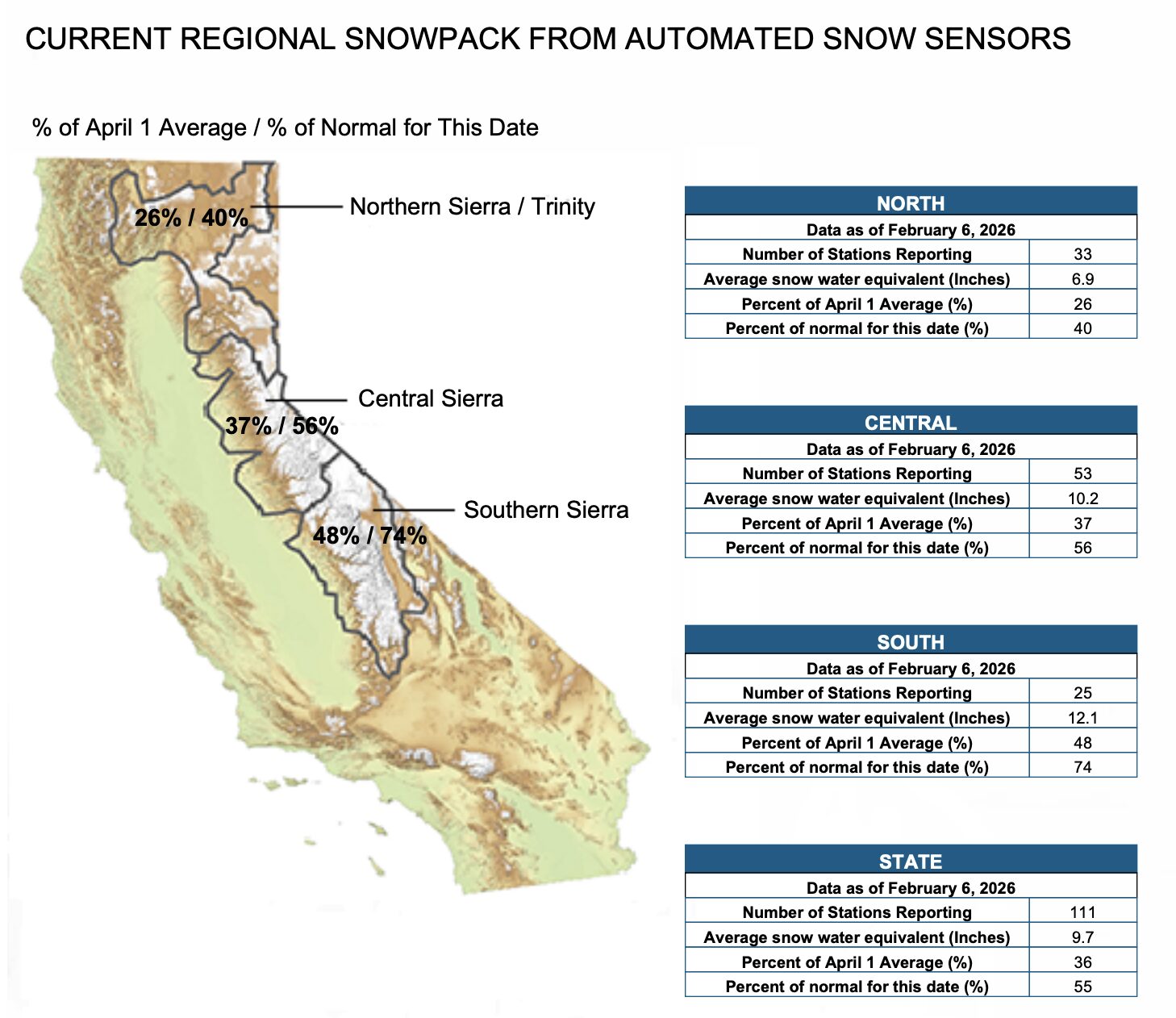

State snow water content counts from Jan. 30.

Even before this storm, the Sierra wasn’t facing nearly as severe of a snow drought as the Colorado and Utah Rockies, where much of the snowpack is the lowest on record for this time of year. Early rains and three previous years of wet winters mean that California’s reservoirs still have more water than average, and plenty stored up for human use this spring and summer. And, when it comes to California’s beloved winter activity of skiing, even just a few spurts of snow every once in a while are good enough to keep the resorts running and people happy.

But the big problem, Swain notes, lies in nature’s dependence on an annual process of gradual snowmelt throughout the spring and early summer to feed the soil, rivers, creeks, and reservoirs. That means trees and other plant life normally have enough water to survive even during the dry and hot season. But if the snow is gone by April or May, instead of in July or August, the forest may start to run out of water during the hottest months of the year, which could cause fires.

“That’s the kind of thing we may see throughout the west this summer if this snow drought continues,” Swain says. “We may end up seeing much more activity in the high elevation forests than we’ve seen in recent years because this lack of snowpack in the winter and perhaps the spring and beyond really would drive an increase in dryness during the peak of fire season.”

Higher elevation fires are mainly caused by lightning instead of by accidental human activity, Swain notes, which can make them harder to contain, in addition to being harder to reach because of their location. First responders may allow some remote fires to burn up to a point, like a highway crossing, he says. Wildfires like this are a natural process, but the difference today is that they’re burning in a warmer climate than ever before.

A drone view of the Phillips Station meadow, where the state completes one of its snow surveys. Photo: Sara Nevis

Both Swain and Reising emphasize, however, that it’s still too early to know for sure how the Sierra will end the winter.

The good news is this week’s snow, which is just what the doctor ordered. Other parts of the West might not be so lucky, though.

“It’s unclear at this point what this year’s higher elevation fire season is going to look like in California because it’s really going to depend on what happens the rest of the season. But in a lot of the rest of the West, signs are already pointing to a ‘Yikes’ situation,” Swain adds. “As much as I wish this was a fluke, unfortunately it’s not. This is part of a sustained long-term trend toward less snowpack overall in the American West, more really low snow years, and more record high temperatures. It’s going to be tricky for ski resorts. It’s going to be tricky for water and fire managers.”