The Hardest & Most Important Thing to Do Next: Education

This August, BCDC approved a public sea level rise education program in lieu of a fill removal project. The vote reflects a carefully negotiated rethink of the public benefits to be derived from requirements in the Exploratorium’s redevelopment permit for Pier 17.

The kid wanted a scraper. And once he had it, every kid on the Exploratorium’s waterfront on Bay Day this past August wanted one too, says oceanographer Jim Pettigrew.

The job was to clean the critters and slime off the Exploratorium’s NOAA monitoring buoy, which bobs between Pier 15 and 17 in San Francisco. The buoy, part of a network along the Pacific Coast, measures carbon dioxide in the air and water. Every year during the buoy’s annual maintenance, the Exploratorium invites visitors to help scrape and scrub while learning about ocean science at the same time.

“The kid’s name turned out to be Davey, and he came three days in a row to help,” says Pettigrew.

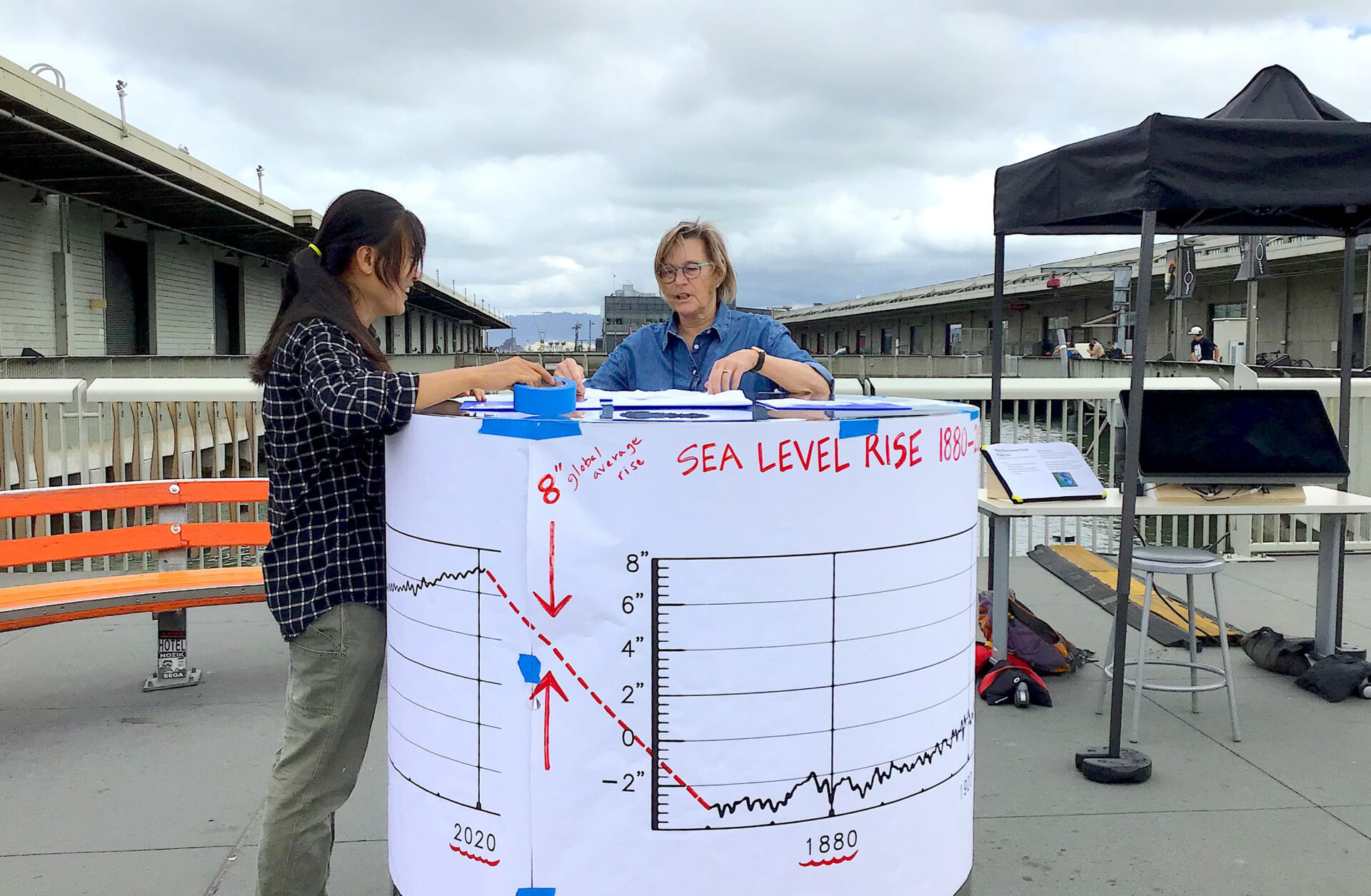

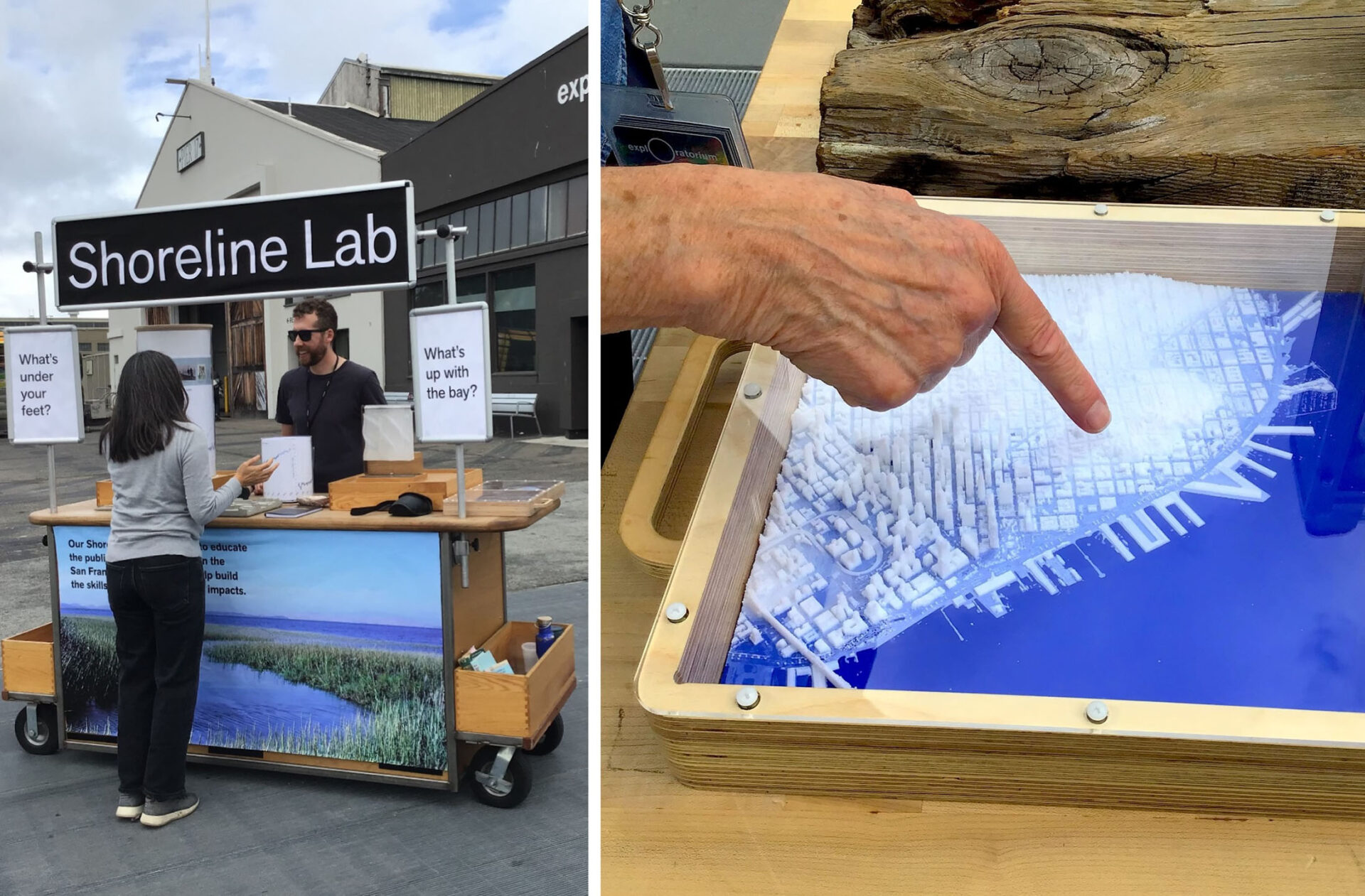

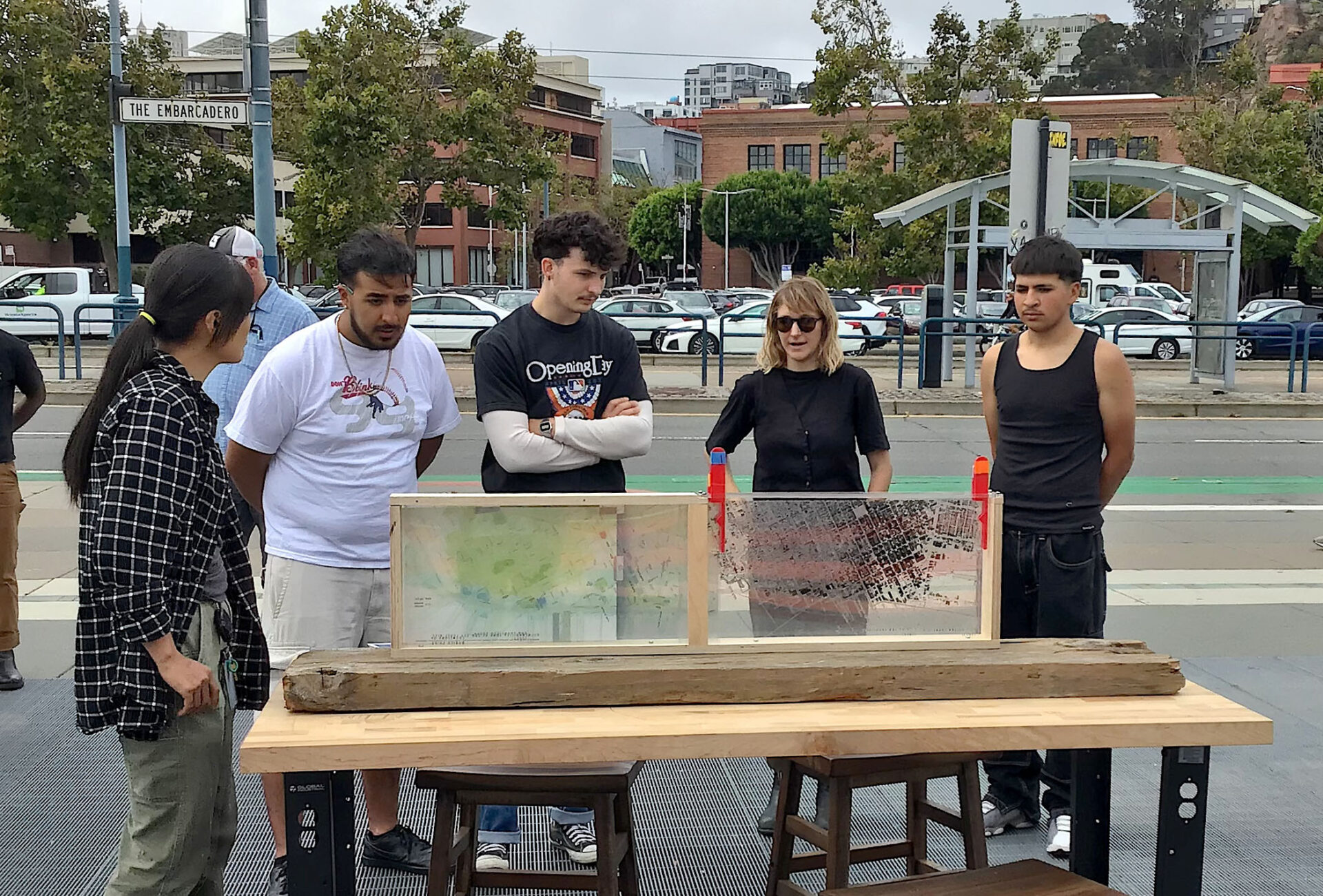

That kind of hands-on, place-based activity was on view this September at the Exploratorium’s most recent “pop-up” event on the Embarcadero sidewalk. The pop-up aimed to educate the public about what lives in the Bay, CO2 levels in the water, ocean acidification, sea level rise, and more. It included a shoreline lab, touchable waterfront models made on a 3D printer, charts, and a digital screen for exploring flood scenarios.

“Place-based education is about the local, about where you live. That’s where you can most intimately connect to what’s happening exactly in a place,” says the Exploratorium’s Susan Schwartzenberg.

Field lab on the sidewalk. Photo: Ariel R Okamoto

In recent months, she and the museum team have been busy “rearranging, retuning, and reconceptualizing” the exhibits inside their 10-year-old Bay Observatory so they can better impart the local impacts of sea level rise outside on the sidewalk where thousands of locals and tourists from all over the world pass by. Why? It’s the first step in implementing a new partnership with local agencies aimed at ramping up public awareness about the rising bay.

“This partnership is enabling us to remake exhibits to tell a more complex story, while also adding new exhibits about the sea wall and adaptation strategies,” says Schwartzenberg.

“We want to make it clear that as an institution we’re civically involved in addressing our local climate issues,” she says.

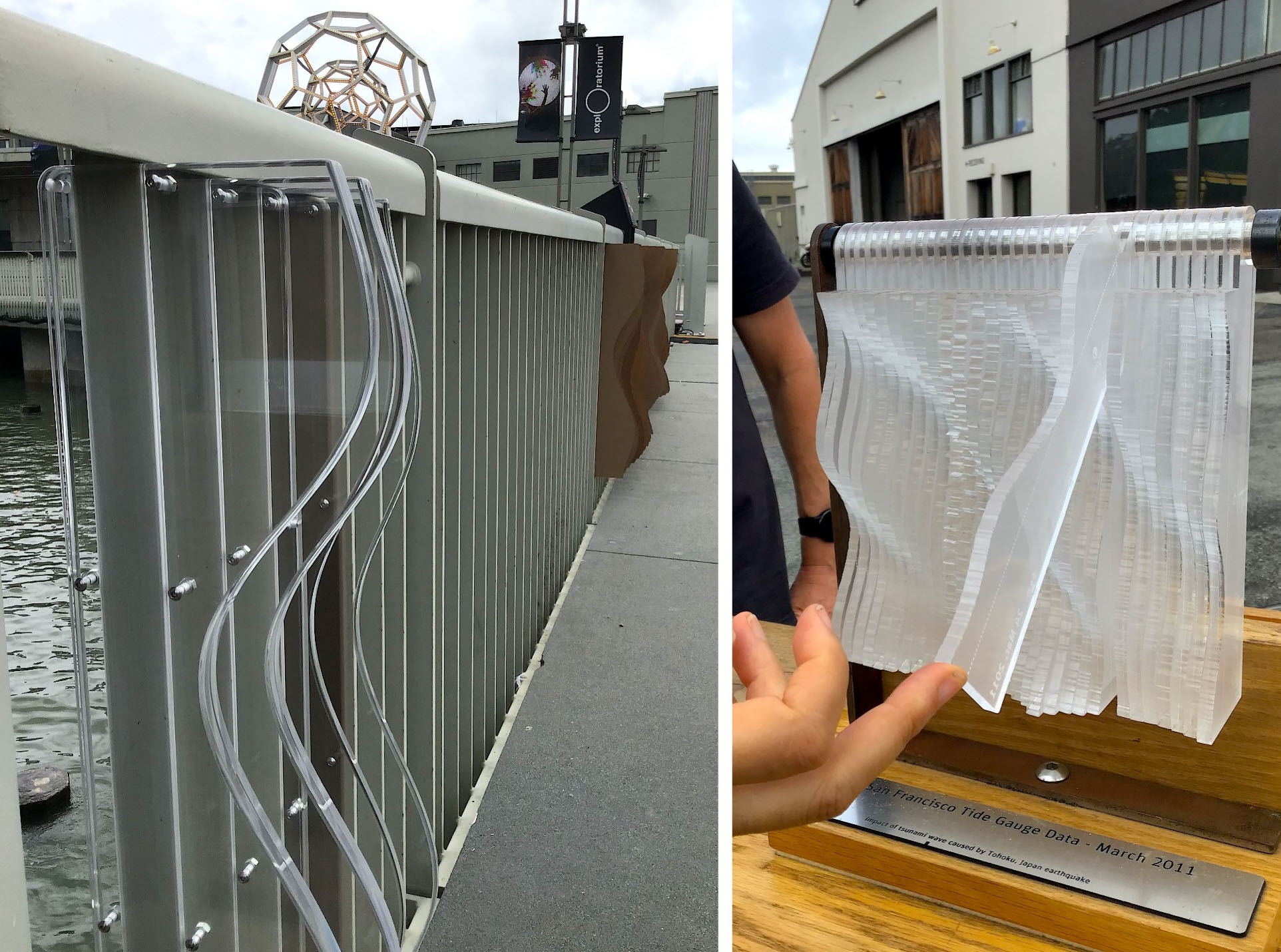

The museum is experimenting with scaling up their desktop “Tidal Ribbon” exhibit (right) onto the pier railing (left). Photo: Ariel R Okamoto

The Impetus

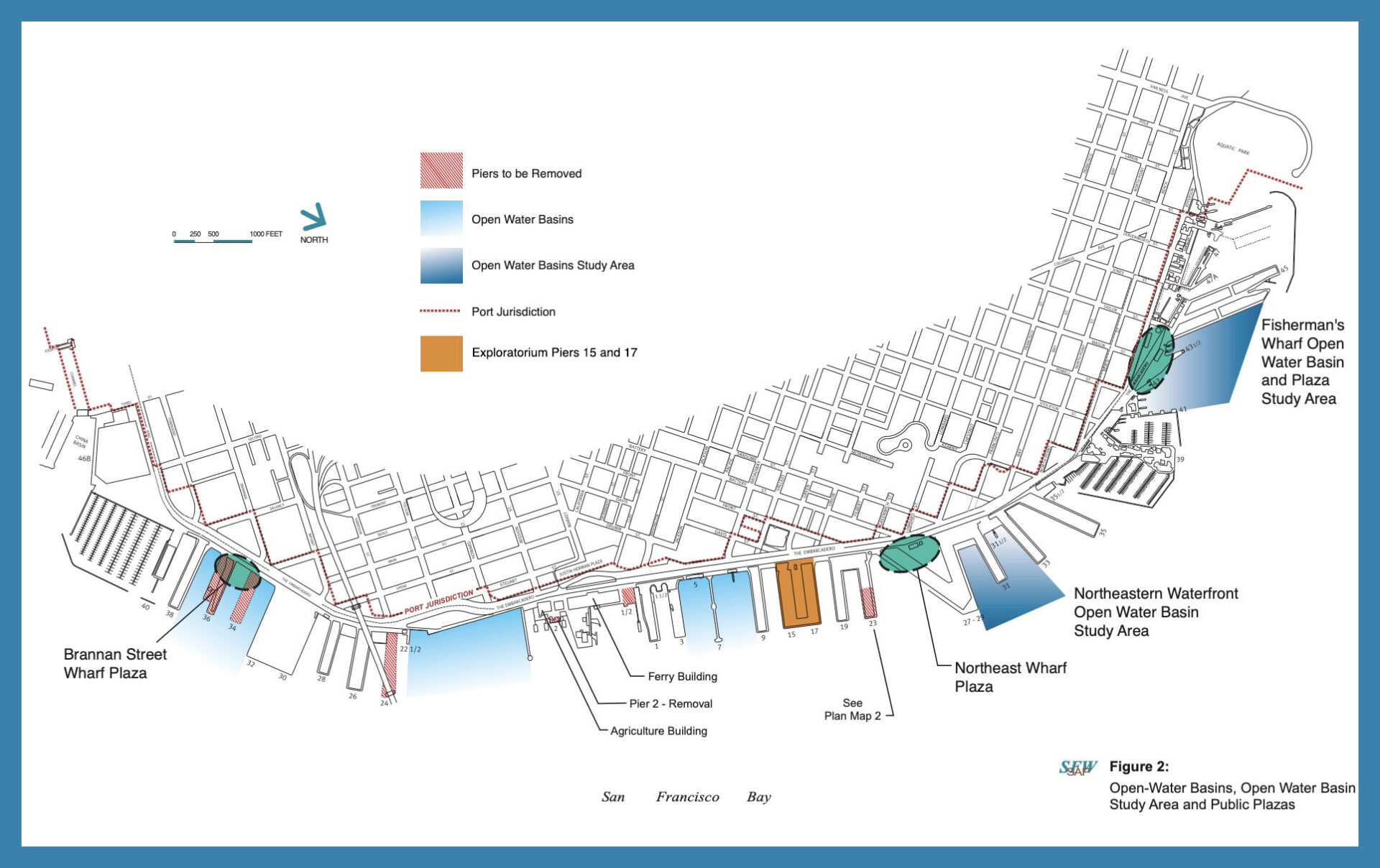

When the Exploratorium moved from the Palace of Fine Arts to Pier 17 in 2013, it gained a gigantic new shed on top of a pier to house its science education exhibits and activities. But in order to keep a parking lot between Piers 15 and 17 built in the 1950s, on top of which the museum planned to erect the Bay Observatory, local regulators required that it remove an equivalent amount of bay “fill” elsewhere. The requirement derived from the piers being part of a historic waterfront district that includes the Ferry Building, and from 1970s era efforts to open up more of the waterfront to the public.

“In the past, we were seeking the removal of old fill so the public could get closer to the Bay,” says Erik Buehmann of the SF Bay Conservation and Development Commission, the regulator. (For more than a century, developers and cities had been filling in parts of the bayfront to create new real estate, which is one reason BCDC was created in the first place: to stop rampant fill and protect waterfronts for public benefit.)

A 2000 update of the 1970s era San Francisco Waterfront Special Area Plan changed those rules. The update allowed for more non-water oriented, public benefit uses of San Francisco’s northeastern waterfront that were also more attractive to investors (resulting in popular projects like the revived Ferry Building and the Cruise Ship Terminal at Pier 27, and surrounding plazas).

Elements of the 2000 San Francisco Waterfront Special Area Plan created by the Port of San Francisco and BCDC, showing the Exploratorium site and pier spanning parking lot where the Bay Obervatory now stands (orange). Map: BCDC

While the plan updates didn’t exempt the Exploratorium (and its landlord the Port of San Francisco) from the fill removal requirement, they did open the door to other solutions. In truth, the museum had struggled to find a way to get its education-minded donors behind the $2 million plus price tag to do what amounted to a heavy engineering project. For seven years, negotiations between the museum, the Port and BCDC dragged on, and in the meantime things changed.

“There’s been a gradual but significant reduction in the number of possible fill removal projects along our waterfront, so much so it was becoming difficult to find a project that would meet the Exploratorium’s permit requirements,” says the Port of San Francisco’s Diane Oshima.

Early this September, BCDC voted that instead of removing fill, the Exploratorium could do something much more up its alley: conduct a free sea level rise education program for the public.

“Our common ground was stronger than any of the details that prevented progress in the past. We recognized how interrelated our work was,” says Oshima. “Credit goes to BCDC for recognizing, despite its singular devotion to fill removal all these years, that there are new needs to be met on the bayshore. In the current political and regulatory climate, I take this as a positive, a little shiny diamond.”

Piers 15 and 17 (at right, where the Exploratorium is housed), with the Bay Observatory in the distance. Photo: Ariel R Okamoto

Regulatory Creativity

In retrospect, reflects BCDC’s commission chair Zack Wasserman, it took a long time to get “everyone’s mind wrapped around the concept” of endorsing the Exploratorium’s sea level rise education project.

In the end, they settled with the port and the museum on a “negotiated additional public benefit that represents a creative and thoughtful way to take our regulatory authority to the next level,” he says.

BCDC Chair Zack Wasserman speaks at the Bay-Adapt Summit last year. A second summit is planned for Sept. 15, 2025. Photo: Karl Nielsen

And next level thinking was definitely in order, as sea levels continue to rise. Scientists project a sharp acceleration in rise as early as 2030.

“The damage might not be so immediate as we’d see with a wildfire, but the ultimate threat is the flooding and disruption of our transportation systems, from our highways to our railroads to our airports and BART,” says Wasserman. “Without taking adaptation measures, the costs in terms of flooded infrastructure, not to mention natural habitats we all value along the bayshore, could be over $230 billion, and that’s with a ‘B.’”

Wasserman describes BCDC’s work to tackle the mind-blowing challenges of sea level rise for the region’s metropolitan waterfronts as occurring in three waves. The first wave was figuring out the science and mapping the flooding; the second was how to source enough material to build levees and elevate shores, while adapting waterfronts in an equitable way; the third was how to finance so much adaptation. “Real waves don’t come just once, they come over and over again,” he says.

To ride these waves, BCDC has had to change its regulatory stance as well. In 2011, it amended the region’s Bay Plan accordingly, and later committed to the development of a regional shoreline adaptation plan. “We had to come to grips with how to fully pivot from an organization highly focused on stopping fill to an organization that recognizes we have to put things in the bay to adapt — natural levees, sediment, plants, and [other buffers and barriers]…” says Wasserman.

After a decade of waves, BCDC’s resulting Bay-Adapt program even has metrics that allow the public to track progress. The program’s regional platform also calls for education and storytelling, recognizing that nothing can happen without public awareness and approval. “We need to educate people so we can create the demand to assemble the funds necessary to minimize damage to our shores,” says Wasserman.

Learning in Place

Back at the sidewalk pop-up in front of the Exploratorium this September, three 20-something dudes stop to look at the models and maps. They seem interested, spend at least 15 minutes looking at the Shifting Shores exhibit and ask questions before moving along on their walk, which I tell them is actually on top of the underwater sea wall protecting San Francisco. They look at their feet, surprised.

Passersby discover sea level rise impacts where they’re standing, on a metal grill through which they can see the Bay. The museum hopes to create a seawall viewer showing this critical piece of 19th century infrastructure under the Embarcadero. San Francisco's seawall needs massive reinforcement to withstand future currents and tides. Photo: Ariel R Okamoto

Out there talking to the general public, it’s hard for anyone to ignore the underlying challenges to this critical climate adaptation and social equity work deriving from new political priorities on the federal side, which include the withdrawal of many grants aimed at disaster response and resilience to extreme weather.

“We’re going to hurt and hurt for many years from the policy changes coming out of Washington, but the Bay Area, and our Commission, remain strongly committed to community and equity in our climate adaptation work,” says Wasserman.

Indeed, the effort to develop a powerful and meaningful education plan saw the Exploratorium consulting with many of its long-established community and educational partners. They’re co-working with local tribes on the installation of a Waterfront Ohlone Trail; they plan to hold pop-ups of the Shore Station in communities most impacted by sea level rise.

They’ll also deepen their discussion of sea level rise with the nearly 100,000 field trip students who visit the Exploratorium each year (59% came from disadvantaged schools in 2024), and continue a partnership with Mycelium Youth Network to create an intergenerational “gaming for justice” role-playing activity around sea level rise. And they won’t shy from looking at regional maps and showing others how planning inequities like redlining have contributed to environmental racism.

And of course, they will do all this through the lens of science. “We make sure climate science is communicated correctly and well,” says senior scientist Melissa Lunden, a new hire for the Exploratorium’s new initiatives.

“We’re respected as neutral ground that locals trust when it comes to science,” adds the Exploratorium’s Emma Greenbaum.

Let’s hope this new education program — growing more visible by June 2026 on the San Francisco waterfront — will help locals gain the knowledge and life skills needed to confront one of the region’s wickedest problems to date: an expanding Bay.