Suisun Marsh, a Zone of Potential in a Sinking Ecosystem

Every few years, it seems, we remember Suisun Marsh. Not that this unique middle chamber of the San Francisco Estuary is ever forgotten; it’s just that, like a relatively quiet child in a troubled family, it can slip into the background.

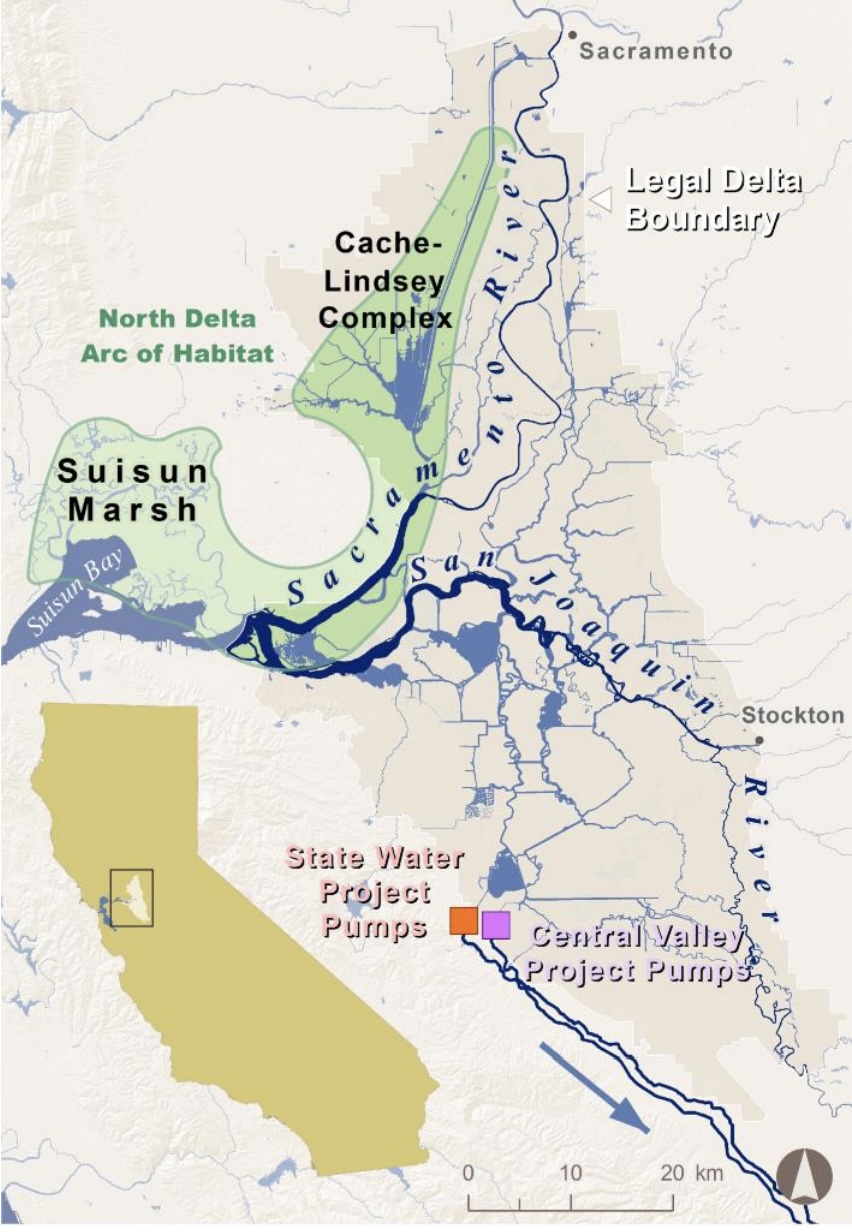

Suisun is a bit downstream from the Delta tunnel battles, a bit upstream from the worst urban sea-level rise concerns. The managed wetlands at the heart of the 107,000 acres legally defined as Suisun, though different from the tidal marshes of the past, support thousands of waterfowl and also pump out food for fish. Suisun is part of what biologists call the North Delta Habitat Arc, a sweep of relatively healthy waters and wetlands running from the marsh eastward past Sherman Island and on up the Sacramento to the Cache-Lindsey Complex and the southern Yolo Bypass. In a stubbornly declining Delta ecosystem, it is a zone of potential, even hope.

But two things are moving Suisun back into the news: a fresh report from the San Francisco Estuary Institute, and the prospect of major development along the marsh’s borders.

Suisun affairs are guided by the Suisun Marsh Habitat Management, Preservation and Restoration Plan, adopted in 2013 by a gaggle of powerful agencies. It sets four goals for 2043, three promising continuity and one offering modest change. The plan undertakes to repel salinity, keeping waters brackish (and marshes more productive than the type found around saltier bays). It would strengthen the 200 miles of levees to keep the basic architecture of the place intact. It would retain most of the duck hunting clubs that have shaped and guarded this landscape. But it would also improve the management of those diked lands to help more species, and it would convert 5,000 to 7,000 acres to tidal marsh, in hopes of improving the prospects for native fish.

A year after the plan’s adoption, biologist Peter Moyle and two colleagues looked farther ahead in a book entitled Suisun Marsh: Ecological History and Possible Futures. Moyle & Co. warned that the present managed wetland landscape will become increasingly difficult to defend as the century wears on. They sketched options including a “reconciliation marsh” in which there would be more tidal marshes and fewer duck clubs. Rising water would be countered by promoting peat buildup and by letting the marsh shift landward into bordering uplands. “Our goal,” wrote the authors, “is to encourage managers to look for and implement a plan for a ‘soft landing’ for the marsh ecosystem, rather than waiting for a hard crash caused by rapid environmental change.”

Now comes A Marsh Transformed: Historical Ecology and Landscape Change in Suisun Marsh. Like prior SFEI studies of the lower bays and of the Delta, this one compares the present state of the place with mid-nineteenth century conditions. Without revolutionizing what is known, it adds a new level of detail, in the form of precise numbers and fine-scale mapping. Decrease in tidal marsh area, from 52,802 to 10,161 acres: Check. Decrease in the area of what is called core marsh—excluding a fifty-foot buffer zone—from 38,324 to 10,161 acres: Check. Increase in managed wetlands behind dikes, from 0 to 36,477 acres: Check. Area of diked wetlands that have subsided below mean tide level, 33,410 acres: Check. New acres of tidal marsh since inception of the Suisun Marsh Plan, 1,937, quite distant yet from the minimum final goal: Check.

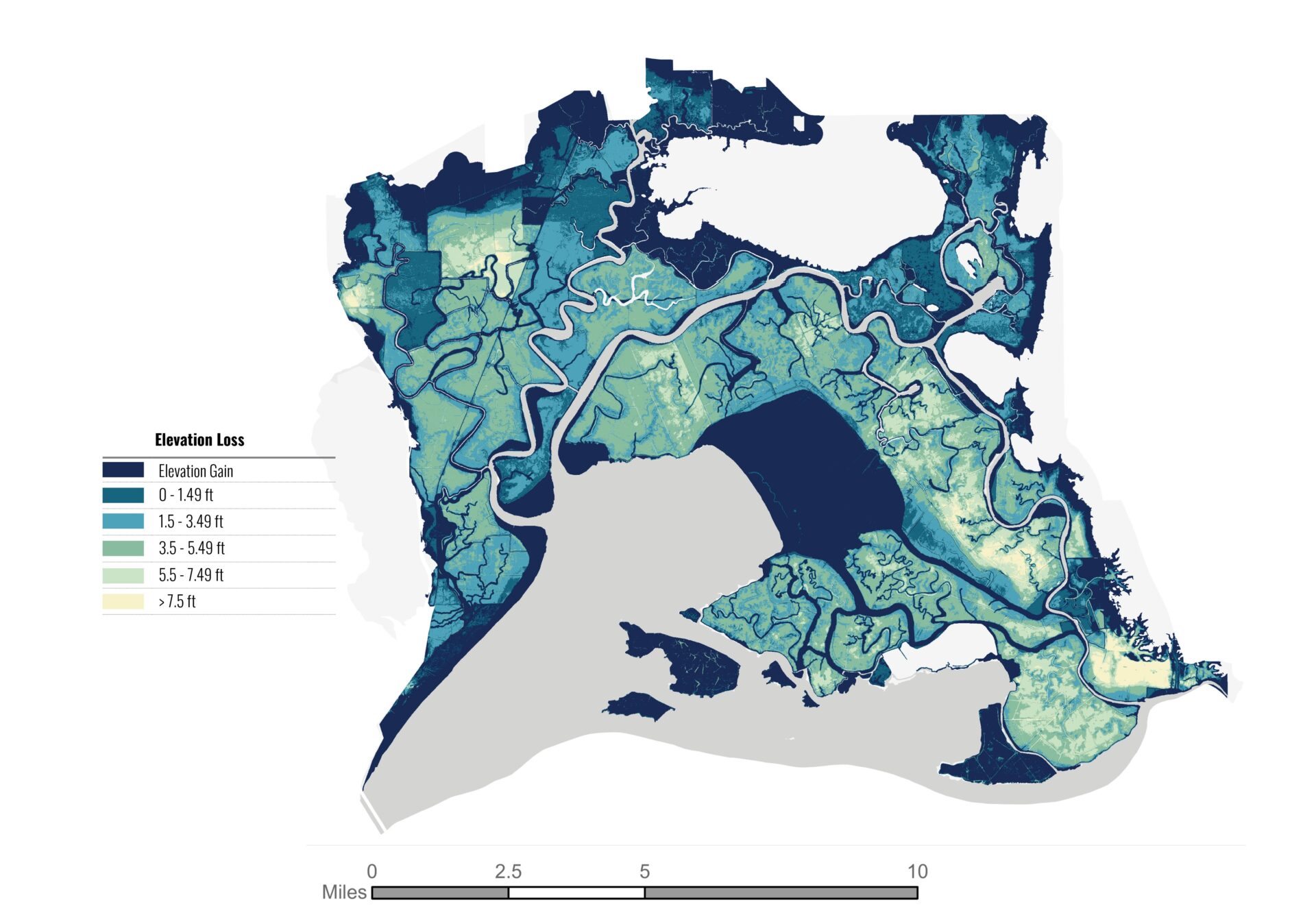

Elevation loss in Suisun Marsh. Map: SFEI, 2024

Such numbers don’t add up to a bleak bottom line. The modern marsh provides “important—but different—habitat for plants, waterfowl, and other wildlife.” Even the subsidence figures here are much less scary than in any other part of the estuary, with less than 2,000 acres deeply subsided (more than 4.5 feet below mean lower low water). And the marsh restoration, now at about 40% of the lowest target, is about on pace for this stage in a thirty-year plan.

Reassuring, perhaps. Yet one section in this mostly retrospective report peers into the future, and this one gives pause. Compared to the 2013 Plan, or even to the 2014 book, SFEI is gloomier about the race with sea level rise. Diked wetlands are still losing soil each year, not building it; and re-tidalized areas are sometimes disappointingly slow to revegetate and start building soil. Here as elsewhere around the estuary, modeling suggests, tidal marshes “are vulnerable to submergence by the end of this century and will see widespread shifts to low marsh or unvegetated mudflats.”

In Ecological History and Possible Futures, Moyle and colleagues warned of “a geomorphic threshold between alternative futures”: early action was needed to get ahead of sea level rise and retain much of the marsh as a marsh. Do SFEI’s data suggest that the threshold has already been surpassed? “I wouldn’t say that the ship has sailed,” says Lydia Vaughn, the study’s lead author. “But we don’t have a lot of time. If we wait, it becomes much more stark.”

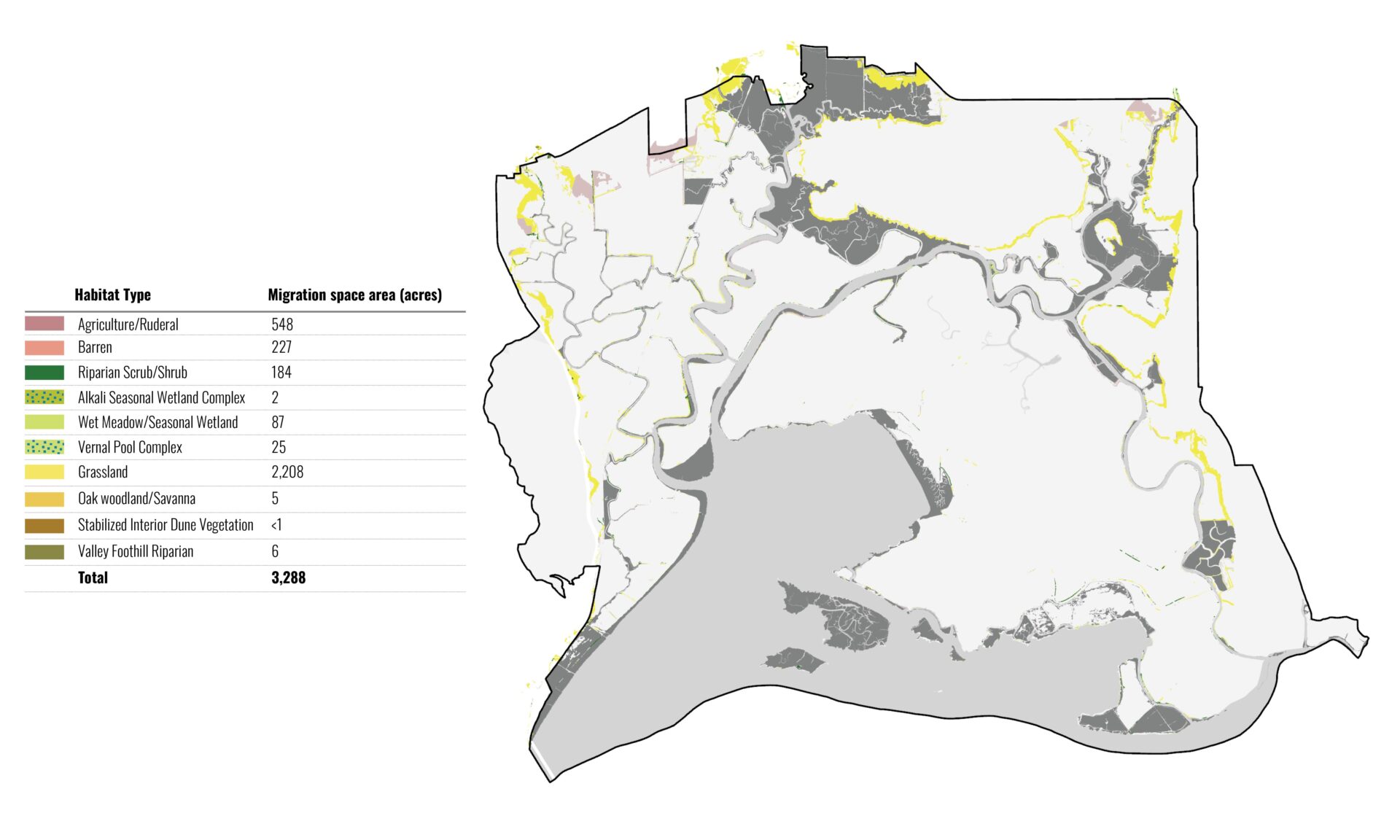

Given the risk to existing wetlands, attention shifts to the marginal areas that the marsh might colonize. SFEI maps this “migration space” in punctilious detail. There is more of this wriggle room adjoining the rims of Suisun than elsewhere around the San Francisco Estuary: 3,208 acres that lie within two vertical meters (6.6 feet) of current sea level. Three quarters of this land is privately owned and without protective easements, and one quarter lies outside the legislated boundary of the Marsh planning area. SFEI implicitly asks that more be done to keep these lands available. “This is where the magnifying glass needs to go,” Vaughn confirms. Protecting such areas is a “no regrets” move. Even if the water doesn’t lap as high as feared, these lands will be precious as “transition zone,” the biotically rich borderland between wet and dry.

Migration space in the marsh is scarce. Map: SFEI, 2024

Possible Futures had made an even bolder claim for migration space, saying that we should “conserve undeveloped lowland plains and valleys with low-intensity agriculture to accommodate sea-level rise of at least 3 meters” (nearly 10 feet). “Conserving them for future passive estuarine expansion is a regionally unique opportunity.”

The uplands around Suisun are no longer guaranteed to be “undeveloped lowland plains and valleys.” In 2023, a consortium of investors, having already purchased some 62,000 acres of land, announced a plan for a new city west of Rio Vista. “California Forever” would cover 17,000 acres north of California Highway 12, just across the road from the legal boundary of Suisun Marsh.

Would such a development preempt Suisun Marsh migration space? It depends on what sea-level rise projection is plugged in. The consortium says its new community lies almost entirely above the 2.5 meter (8.3 foot) line. That is midway between the flooding levels assumed by SFEI and by Moyle & Co. With two meters of rise, the development and the expanding marsh wouldn’t clash. At three meters, they very likely would.

Imagined opportunities for city dwellers to connect with local open space and marshes in Suisun Marsh from the proposed new town in Solano County. Image: SITELAB urban studio_CMG

Biologists also point to a regional connection that extends beyond the borders of the marsh and skirts the California Forever site: a band of superior habitats beginning with Denverton Slough at the northeast corner of Suisun, running north to the vernal pools of Jepson Prairie, and turning east to Lindsey Slough in the northwest Delta. The land along this swath lies so low that the Sacramento may once have sent some of its flow this way. Highlighting this corridor turns the North Delta Arc into a kind of North Delta Circle. The new town would not directly intrude on this ring, but would dominate the space within it. Renderings on the California Forever website seem to show these sloughs as parklike adjuncts to the city; the backers have offered a land swap that would consolidate public ownership along the corridor. Symbiosis, or fatal contradiction?

California Forever (the name of the company as well as of the proposed town) also owns land much more obviously linked to the marsh: the Collinsville area on the banks of the Sacramento River and adjoining the successful Montezuma Wetlands marsh restoration. Following a prompt from the Trump Administration, the firm has jumped on the idea of a major shipyard at this spot. Though Collinsville has tempting access to deep water, and is in fact zoned for industry, its development would be extraordinarily challenging even without considering impacts on Suisun. “There’s a great big levee in the way, for starters,” says John Durand, currently a leading researcher in the marsh.

This debate aside, what’s next for this vital region? At present, officialdom is focused on fulfilling the Suisun Marsh Plan. “We’re making good progress,” says Rosemary Hartman of DWR. Since the plan is just entering its second decade, the partners are not yet talking about the next iteration.

People outside of government are freer to look far ahead. Prior reports of the San Francisco Estuary Institute have looked at the past, present, and future of the lower bays and of the Delta. A Marsh Transformed brings us up to date for this last sub-region of the estuary: one step to go to make the set complete. “We hope that there will be a next phase that is forward looking in Suisun,” says Lydia Vaughn. “We are looking for a source of funds.”

This story also appeared in Maven’s Notebook in July 2025.