Vote Cinches Robust Regional Response to Sea Level Rise

On December 5, a sprint was over; a marathon began. The Bay Conservation and Development Commission unanimously adopted its Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plan, meeting a state deadline and shifting the pressure to local governments that must now write “subregional” plans for dealing with sea level rise. These are due at the end of 2033: a distant due date in the face of global change, but maybe a quick one considering the complexity of the task.

After RSAP’s first release in September, there was push and there was pull. Local governments and others objected to some of the mandatory standards proposed, calling for “flexibility.” A November draft tacked in that direction, changing quite a few “musts” to “shoulds” and demoting some of the Standards to “planning tips.” Now it was the turn of the environmental coalition, some forty groups, to decry a “watering-down.” Further redrafting ensued.

The result of these contending pressures seems, surprisingly, to please nearly everyone nearly well enough. “We seem to have found the sweet spot,” says BCDC planning director Jessica Fain. The Sierra Club’s Gita Dev agrees: “We are very happy with the results of the RSAP. Now,” she goes on, “it’s time to get serious about execution.”

Local governments are clamoring for support for this new task. BCDC is devising a technical assistance program. With passage of November’s Proposition 4, the Ocean Protection Council will have more funds to grant. To ease the burden and clarify the options, counties and cities around the Bay are looking at doing combined, multi-jurisdictional shoreline plans.

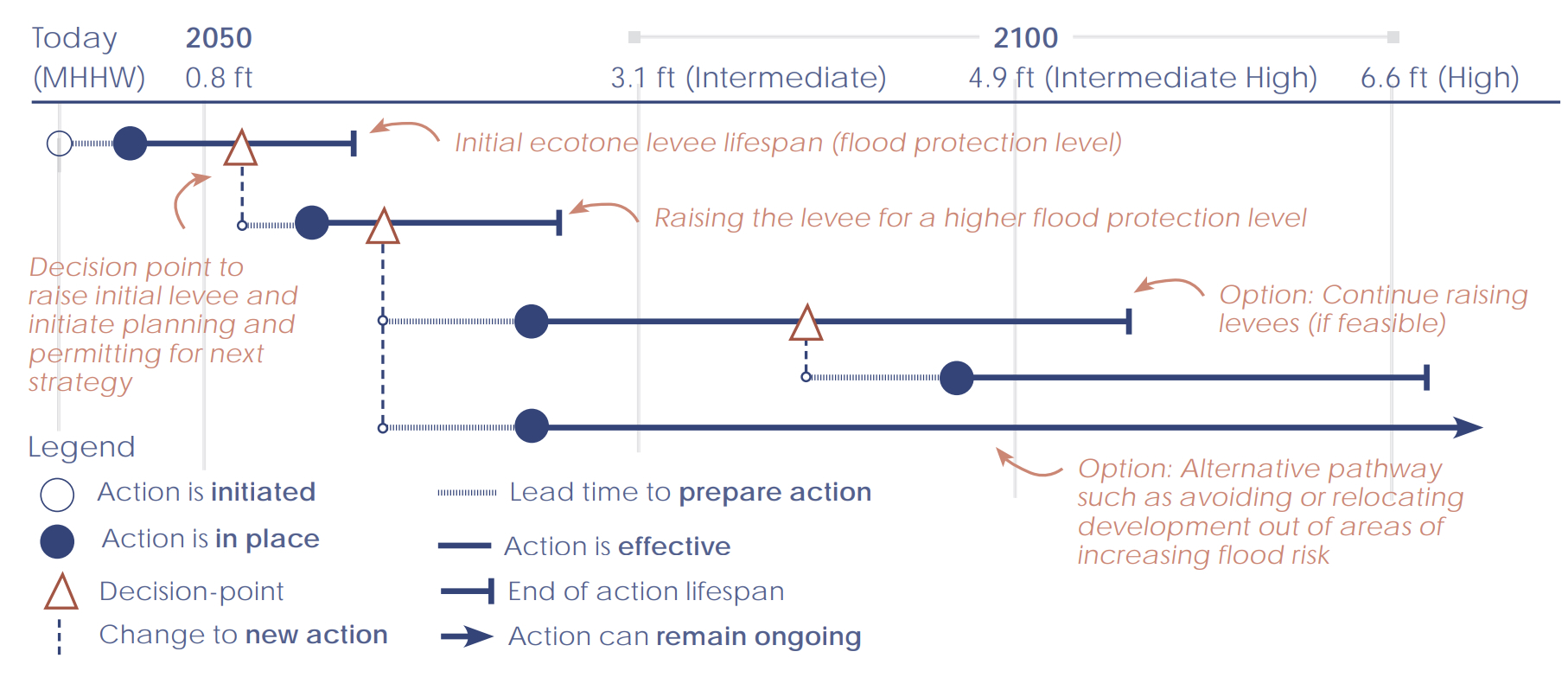

Diagram of how adaptation pathways can unfold. From Werners et al, Environmental Science & Policy

BCDC is also pondering another trip to Sacramento. Under last year’s SB 272, which started this planning ball rolling, the agency can only advise about the plans being prepared — until the moment when they are completed. Then the bay regulators can say “Yes” or “No,” but the sole result of a “No” is that a city or county drops down the priority list for state funding. “The Legislature has taken us halfway,” BCDC executive director Larry Goldzband remarked last summer. Should the agency now seek a stronger hand? “We are planning to lean into that question in 2025,” says Fain.

Top Photo: King tide in Alameda in November 2024 by Maurice Ramirez

Other Recent Posts

Building Sustainably with Mass Timber

This building method can help clear forests of smaller trees that burn easily while also reducing the carbon footprint of new homes and offices.

Hardscapes That Filter Rain

Heavy rain can overwhelm storm drains and pollute waterways, but materials like permeable pavements help filter runoff and prevent flooding.

The Gray-Green Alchemy of Baycrete

Baycrete is a nature-based hybrid of concrete, shell, and sand designed to attract oysters and create shallow water reefs in SF Bay.

Tools Tweak Beaver Dams

Humans find ways to co-exist with beavers, tweaking dams to prevent flooding and create more climate resilience.

Hopes and Fears for Sierra Snowpack

February’s drought and deluge confirms that uncertainty may be a given for California snowpack, western water supply, and wildfire risk.

Errands by E-Bike

Electric cargo bikes are climate-friendly car replacements for everyday activities, from taking the kids to school to grocery shopping.

A Rare Plant Tough Enough to Save the Future Bayshore

Sea-blite can thrive in adverse conditions, buffer shores from waves, hold sand and soil in place, and clamber up eroding cliffs.