Resisting Retreat for Coastal Communities?

In the coastal getaway town of Stinson Beach, king tides and storm surges regularly put roads and parking lots underwater: wintertime events that give locals an unnerving idea of what rising sea level will look like for the small community. “We know sea-level rise is coming, but here, we say we’ve already got it,” says Stinson Beach homeowner Jeff Loomans, also the president of the Greater Farallones Association, which has been active in sea-level rise planning.

Rising sea level is no longer a distant matter of if or when. Firm science and unyielding line graphs into the future make it clear: the swelling ocean is a reality that is shaping state development policy and challenging coastal communities. Pushed forward by the unstoppable momentum of global warming, repeating waves gnaw at the shore, causing beaches to vanish and sea cliffs to crumble. And homes that once offered residents a piece of the California dream now serve as seaward windows into the uncertain future of coastal living.

The ocean rose about six inches during the 20th century and it could rise six to 10 feet more by 2100—a slow-motion tsunami. For some shoreline landowners, the implications seem simple. “We can either fight it or retreat,” says Willy Vogler, whose family owns a share of Lawson’s Landing, a 1,000-acre coastal property at the north end of Tomales Bay. Several feet of sea-level rise will flood this campground and boat-launching destination, and while the site’s owners are now studying their options for what to do as the water rises, Vogler and his family —owners here since 1928—are fortunate enough to have an escape route: The parcel includes the hillside just east of the water’s edge. “We could just back up the hill,” Vogler says.

A few miles south, in Marshall, the options are fewer. “There’s a bluff right behind us—retreat isn’t an option for these homes,” says George Clyde, whose house stands on pilings over the water of Tomales Bay. Nor is relocation a viable option for most of the homes at Stinson Beach. The town is backed by both the waters of Bolinas Lagoon and the protected slopes of Mount Tamalpais.

Managed retreat involves gradual planned steps away from the rising ocean and more powerful waves of the future, rather than disaster response. Map courtesy ESA.

“People talk about ‘managed retreat,’ but retreat to where?”

“People talk about ‘managed retreat,’ but retreat to where?” says Jack Liebster, advance planning manager for Marin County. The prospect of managed retreat is especially unpalatable in Pacifica, where the community has debated whether to protect the shoreline with cement and rock or move back and allow the Pacific Ocean to migrate inland. Sea walls and piles of riprap can, at least temporarily, protect vulnerable structures from rising waters, but they have a very negative side effect: by preventing natural sand replenishment from inland deposits, such wave barriers can cause a beach to disappear at the foot of a sea wall. This makes rigid shoreline protections very controversial and generally unfavorable to state planners and many environmentalists.

Sam Schuchat, executive officer of the California State Coastal Conservancy, believes fighting the swelling ocean is a battle people will only lose and that many, if not most, vulnerable communities will eventually have to retreat. “Nothing that we build is going to protect us for very long,” he says.

The diverse geography of the California coast, and each community’s integration into its particular landscape, makes sea-level planning very complicated. So do stiff regulations on new coastal developments, which can impede homeowner efforts to upgrade their properties as the waters rise.

Demographic variation among coastal dwellers also shapes the way different communities grapple with rising sea level. Poorer communities seem likelier to be lost—like Imperial Beach, at the border with Mexico. Here, the ocean routinely surges onto the waterfront. Projections show inundation of whole neighborhoods in 80 years, and while many residents have called on leaders to fight the ocean, retreat looks inevitable.

Wealthy communities are likelier to be pampered with shoreline protection and mitigation efforts. Del Mar, in San Diego County, has rejected managed retreat as the community looks ahead, and is instead leaning toward enhanced seawall protections. Similarly, Malibu built a rock wall at the high-tide line in 2010 to shield expensive homes on the bluffs above. This has had severe consequences for Broad Beach, which is now nearly gone and becomes entirely submerged at the highest tides. The saga is a classic California example of social beach injustice—sacrificing the public sand to save mansions.

Surfer’s Point, Ventura, site of one of the earliest river mouth, beach and shoreline redevelopment for retreat plans for California’s coast. Project engineered by Philip Williams and Associates, now ESA. Photo courtesy ESA.

At the Surfrider Foundation, California campaign director Jennifer Savage feels the long-term public cost of coastal armoring must be weighed against the private property benefits they provide. Her group has taken a general stance against seawalls as a go-to measure to protect shoreline structures. “With building any kind of hard armoring, we’re making the choice between protecting what belongs to everyone and protecting what belongs to private property owners,” Savage says.

USGS research geologist Patrick Barnard has studied waves and storms to help forecast climate impacts over the next 80 years. He says California’s sea cliffs already retreat at a rate of a foot per year on average (usually in the form of decadal landslides). “That rate could double in the next century,” he says.

Seawalls will only delay the process for a geologic moment. Barnard explains that beach incision caused by seawalls eventually undercuts the barrier itself. This can cause the barrier to topple. In the end, money is spent on ill-fated projects and the sea still consumes everything: wall, property, and cash.

Mitigating beach loss is possible but laborious. Some communities run programs of dumping dredged sand on impacted beaches, but maintaining such life-support efforts in perpetuity is a tall order. Beach nourishment programs in San Diego County, for example, have been both expensive and, in the end, ineffective. “Sand replenishment is not a long-term solution,” Savage says.

Along the heavily developed Southern California coast, seawalls and other revetments line 38% of the shoreline south of Santa Barbara, according to a 2018 report on shoreline armoring from California State University Channel Islands. Among counties, Ventura has taken the firmest stance against the ocean, armoring 58 percent of its coastline.

In Northern California, nearly half the coastline is preserved, and very little is developed. With little infrastructure to protect from rising seas, there has been scant investment in seawalls, rockpiles, and other protections. Sonoma and Marin counties, with 340 miles of coast between them, have armored, respectively, just 1.2% and 4.7% of the coast. San Mateo County, with almost 60 miles of coast, has armored 9%. San Francisco County’s short ocean coastline features a seawall for most of the length of Ocean Beach, but the total coastal mileage is only about 10. (Inside the Bay, the stats are skewed toward heavy armoring.)

Still, there are a few oceanfront towns and scattered structures at risk as sea level rises. Already, several seaside homes perched on crumbling bluffs north of Bodega Bay, at Gleason Beach, have been vacated by their owners, and state roadway officials are planning to reroute a 3,000-foot section of Highway 1 inland approximately 400 feet.

In Pacifica, discussion of managed retreat has met fierce pushback from homeowners like Mark Stechbart. He says a managed retreat program would be far more expensive than the potential alternative of seawalls and beach replenishment. “We would lose a half or a third of the town,” he says. “It would be a billion dollars. Who’s going to pay for that?”

Stechbart says a thousand homes, a shopping center, a sewage pumping plant, an RV park, a golf course, and Highway 1 would have to be sacrificed under a managed retreat regime, which has been discussed in public forums. Facing intense opposition from community members, however, officials released a planning report in February that makes scant mention of managed retreat.

Stechbart lives in a home at the foot of Montara Mountain, roughly a mile inland and 800 feet above sea level. Still, he worries, homes like his will lose virtually all value “if the Coastal Commission gets their way.”

“They very callously want to kiss off everything built in the past 43 years,” he says, referring to a clause in the Coastal Act that allows “existing” structures to be protected with seawalls. But there has been much disagreement over what “existing” means. Lesley Ewing, a senior engineer with the California Coastal Commission, says it describes homes that existed prior to 1977, the year the California Coastal Act became law.

However, some stakeholders see a broader definition of the word. “We think ‘existing’ means what’s there right now,” Liebster says. This is the literal interpretation of the language, he believes, arguing that legislative action is required “if you want to change the meaning of the law.”

Linda Mar shopping center, abandoned and then redeveloped yet precariously close to the crumbling cliffs. Photo: Alastair Bland

But in the era of sound climate science, it’s clear that many coastal projects should arguably never have been built in the first place, and protecting them could mean sacrificing public beaches. At Linda Mar Beach in Pacifica, the waterfront shopping center was little more than a surf shop, a café, and a dirt lot 20 years ago. But in the past 15 years, it has seen major investments and upgrades, including a supermarket and craft beer taproom—all just a few feet above the current high-tide line. Whether such development deserves seawall protection lies at the heart of the local controversy and reflects the significance of the Coastal Act’s debatable language. A 2015 report from Stanford Law School recommended that officials resolve the ambiguity in this particular clause.

Meanwhile, proposed legislation would modify the Coastal Act, clarifying the law in the interests of coastal homeowners in San Diego and Orange counties. Here, building seawalls and other protective barriers will become the right of developers if SB 1090 becomes law. The bill, introduced by Senator Patricia Bates (R-Laguna Niguel) faces impassioned opposition from environmental groups including Surfrider.

Regardless of what is legally obligated, Schuchat thinks protecting Pacifica’s waterfront neighborhoods will be a lost cause. “Even if our resources were unlimited, we couldn’t protect Pacifica,” he says. “There just aren’t engineering solutions that can handle that.”

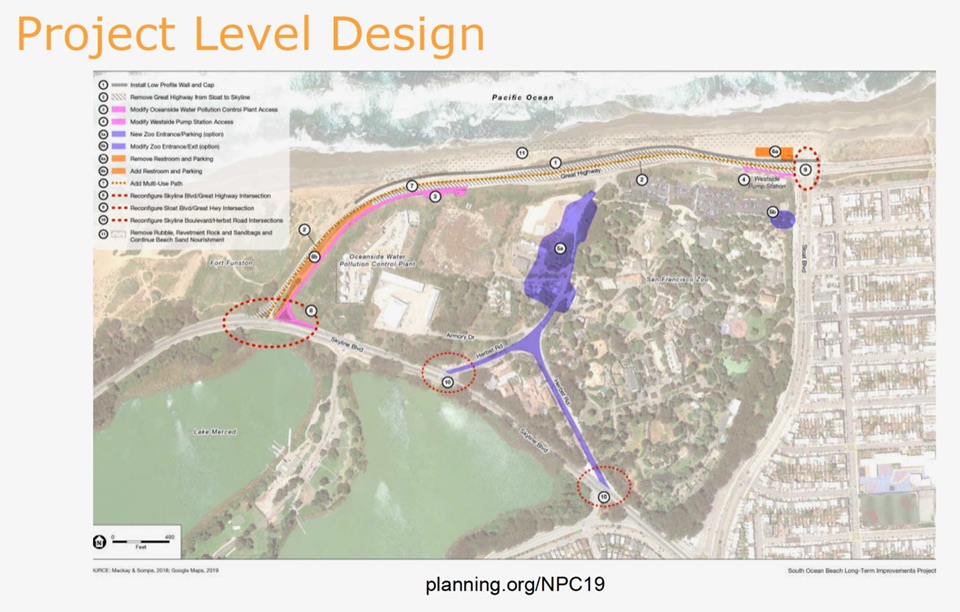

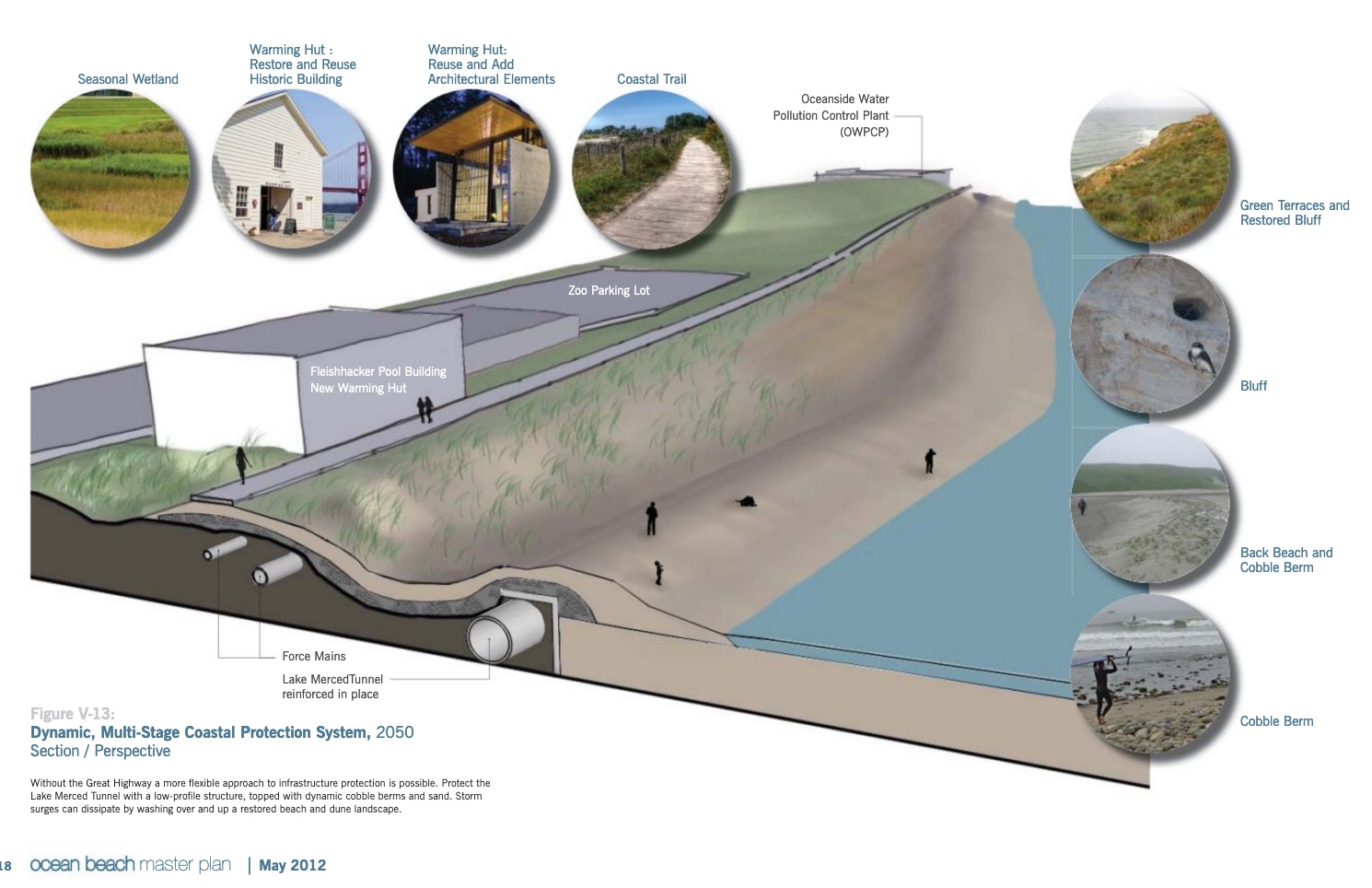

Dynamic design for managed retreat to protect important utilities such as the wastewater treatment plant on the San Francisco shore. Project now underway. Image taken from Ocean Beach Master Plan, SPUR

At the southwest corner of San Francisco, officials are planning to use a touch of both managed retreat and concrete defense to deal with a confluence of challenges. Here, the beach is feeling the squeeze as the rising ocean pushes against the riprap that protects a southerly section of the coastal Great Highway. The city’s plan is to reroute the highway eastward, giving room for the water to move inland without washing out the beach. Simultaneously, a seawall will be built around the city’s sewage treatment plant, which would cost far too much to relocate.

In Stinson Beach, projections show that the sandy strand could be totally underwater by 2100. But there is no firm plan yet to do anything—just a list of ideas. These include protective measures, like seawalls, and adaptive ones, like elevating threatened homes and roadways and relocating a fire station.

There is another idea, too: restoring wetland habitat along Bolinas Lagoon. Such a “living shoreline” would employ native vegetation to hold the soil in place while natural sedimentation adds to the habitat, effectively building the mudflats higher, keeping the shoreline abreast of the rising waterline, and shielding both homes and Highway 1.

“It’s a wonderful solution—a natural, native-plant-based habitat solution that reduces erosion and wave impacts, even as the sea rises,” says Loomans, who owns a home on a sandy spit reaching northward from the town center. “No one wants a concrete wall out here.” Natural solutions are also being discussed at Lawson’s Landing: encouraging beach grasses to anchor sand dunes and building native oyster reefs and eelgrass beds, which would create wave breaks while encouraging the deposition, rather than the erosion, of sand.

For Clyde and others in the town of Marshall, basic foundation improvements could lengthen the lifespans of their homes. However, the Coastal Commission’s regulations make such shorefront upgrades very difficult and costly. In effect, warns Clyde, the Coastal Commission’s policies will fast-track the eventual loss of shoreline homes. “This place will be inundated eventually, but we could get a few more decades of life out of them if they’ll let us,” Clyde says. “We’d like to be able to protect and maintain our homes, and enjoy our resilient communities, until sea-level rise makes that impossible.”

Jack Ainsworth, executive director of the California Coastal Commission, says the agency has been working on approaches to development in coastal hazard areas. “We have been working in close partnership with the County of Marin to develop local coastal policies that ensure the safety of residents, resilient development, and protection of sensitive coastal resources,” he says. “This ongoing process is very challenging. It requires input and buy-in from many stakeholders with diverse opinions on how best to plan for rising sea levels.”

It’s undeniable that those rising sea levels, once discussed as a figment of a foggy future, are happening. Clyde, who is 78 and has closely watched the waterline since moving to his Marshall home in the late 1990s, says he has not seen any obvious change yet in the highest of the high tides. “But,” he adds, “it seems that the lowest tides aren’t quite as low anymore.”

Jennifer Savage of Surfrider lives on the Samoa Peninsula, the sandy spit that shields Humboldt Bay from the ocean. In January, she watched as a storm pushed the water higher than she can recall ever seeing in her 18 years of living there. “The entire beach was underwater,” she says. “I’d never seen that before. It was creepy.”

More

First published by Estuary News Group, June 2020